“In a sense, close reading is a form of defamiliarization we use in order to break through our habitual and casual reading practices. It forces us to be active rather than passive consumers of the text.”

-

Elaine Showalter describes close reading as “a form of defamiliarization we use in order to break through our habitual and casual reading practices. It forces us to be active rather than passive consumers of the text.” In my Writing Identity course, I work to convince students that close reading, an old and decidedly untrendy academic skill, is in fact the most useful one they’ll learn during their first year of college. Close reading is the basic building block of analysis—it demands time, patience, and a tolerance for the boredom that precedes a great idea.

It is also, I believe, a great equalizer. It requires no special computer program, no expensive textbook, no vast and expert knowledge in any particular field. And, despite the taint of traditionalism that attaches to the term, students quickly see that a good close reader is also a reader who has no patience for elitism. The tool is as useful for developing a claim about an artifact of so-called high culture—for instance, Melville’s Moby Dick—as it is for developing a claim about an artifact of popular culture—for instance, Beyoncé’s “Formation” music video. It’s not only students pursing degrees in arts and sciences, but also business students, future engineers, and artists of all kinds who benefit from learning how to think about language and image structurally, contextually, and associatively.

My belief in the importance of this academic skill guides the kind of research paper I ask students to write, which begins with a claim that students arrive at through close reading. In this way, the student—their interpretive work, their synthesis of complex material—centers the essay they write. In Reading the Visual, I’m proud to introduce three exceptional essays by three of my exceptional Spring 2021 students. As you observe the way Lily, Yeetang, and Julia construct persuasive claims about ambiguous and complicated primary texts, remember that Spring 2021 was the third in a series of semesters structured by the pandemic. Although our College Writing class met in person, the three of them and their peers endured a year of Zoom education, only a semblance of campus life, and the uncertainty brought on by a global disaster. In any semester, the work collected here would be outstanding student work. In the context of Spring 2021, it’s even more remarkable.

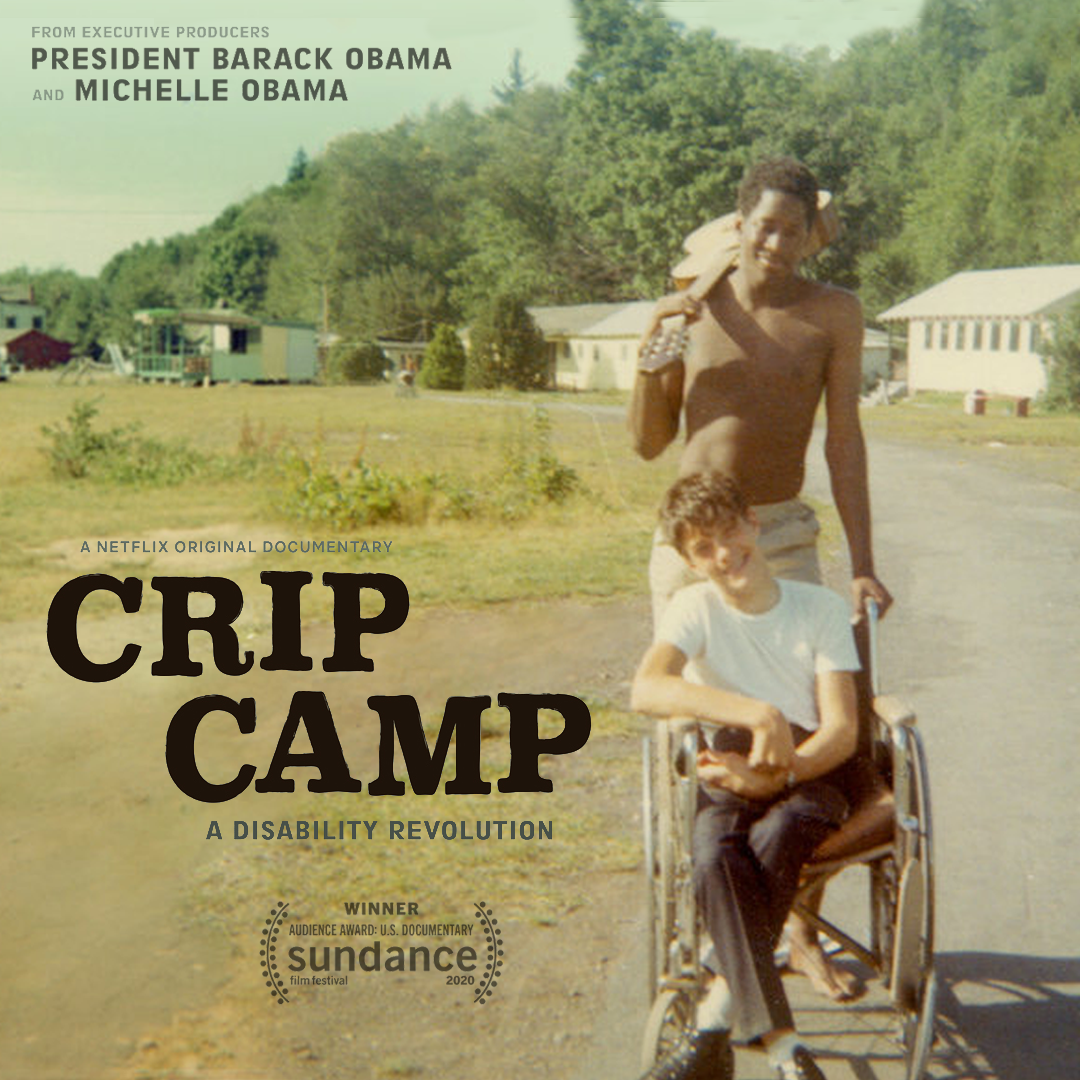

Each of these students takes as their primary text a piece of visual culture. Close reading, already a challenging strategy to deploy, becomes even more challenging when the student has to grapple with visual and auditory information alongside language. But each of these students manages that balance skillfully. Lily, writing about the trailer for the Netflix documentary Crip Camp (2020), points out how “the repeated imagery in which Black people are seen physically supporting white people by pushing their wheelchairs not only racializes the disability rights movement as a white movement, but plays into the dominant depiction of the disabled body as white.” Here, she uses a key detail to make an argument about the trailer as a whole, a signal move of the strong close reader.

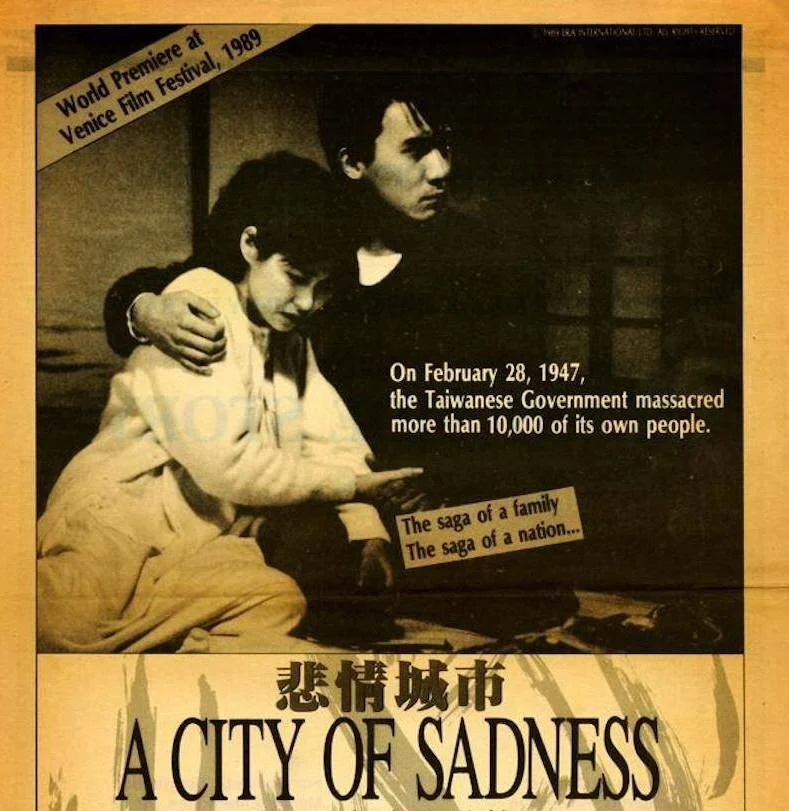

While Lily writes about the way that film can hinder the construction of a shared identity within a marginalized group, Yeetang writes about the way that film can enable the construction of that shared identity, as in the case of the Taiwanese film A City of Sadness (1989). In his analysis of the climactic scene, in which one of the main characters is put to death, Yeetang explains how “the prison scene suggests that the silence of Wen-Ching is a strength, not a disability. Save for some quiet singing and a few words exchanged, the scene is silent. For the first time in the film, Wen-Ching does not stand out as a deaf and mute person. Others in the cell have become more like him, unable to speak out but able to persevere in silence. […] Facing injustice, silence is a form of resistance.” In both Lily and Yeetang’s work, I discern a deep commitment to centralizing non-white and disabled experiences. Close reading analysis provides the foundation for that commitment.

I discern a similar investment in Julia’s essay with respect to women’s sexual empowerment. With the music video for Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s “WAP” (2020) as her primary text, Julia argues that we need to expand our notion of what sexual empowerment looks like. “Although women may be limited by sexual objectification because it shapes their aspirations toward becoming desirable under the male gaze, not all forms of objectification are harmful,” Julia insists, adding that, “In fact, Cardi and Megan’s sexual desirability functions as a tool to access greater freedom, as it is a quality [they] inherently possess to market themselves and their music.”

The work of these students is a testament to the value of a course like Writing Identity, in which students are asked to confront questions of race, gender, sexuality, and socioeconomic class even as they work to develop skills of analysis and argumentation that they can take with them as they pursue varied goals.

Beth Windle, PhD

Lecturer in English, College Writing, and WGSS

Washington University in St. Louis—

Showalter, Elaine. Teaching Literature. Blackwell, 2003, p. 98.

«« A Civil Rights Law of Our Own

Intersectionality and the Disability-Race Analogy in the Trailer for the Documentary Crip Camp

by Lily Coll

Bring a Bucket and a Mop »»

Subverting Cultural Expectations to Celebrate Women’s Embodied Power in Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s “WAP”

by Julia Edelman

«« I am Taiwanese!

A Silent Cry for Taiwanese Identity in Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s A City of Sadness

by Yeetang Kwok

published November 2021

cover image by Joel Filipe