"A Civil Rights Law of Our Own"

Intersectionality and the Disability-Race Analogy in the Trailer for the Documentary Crip Camp

Lily Coll

READING THE VISUAL

— — —

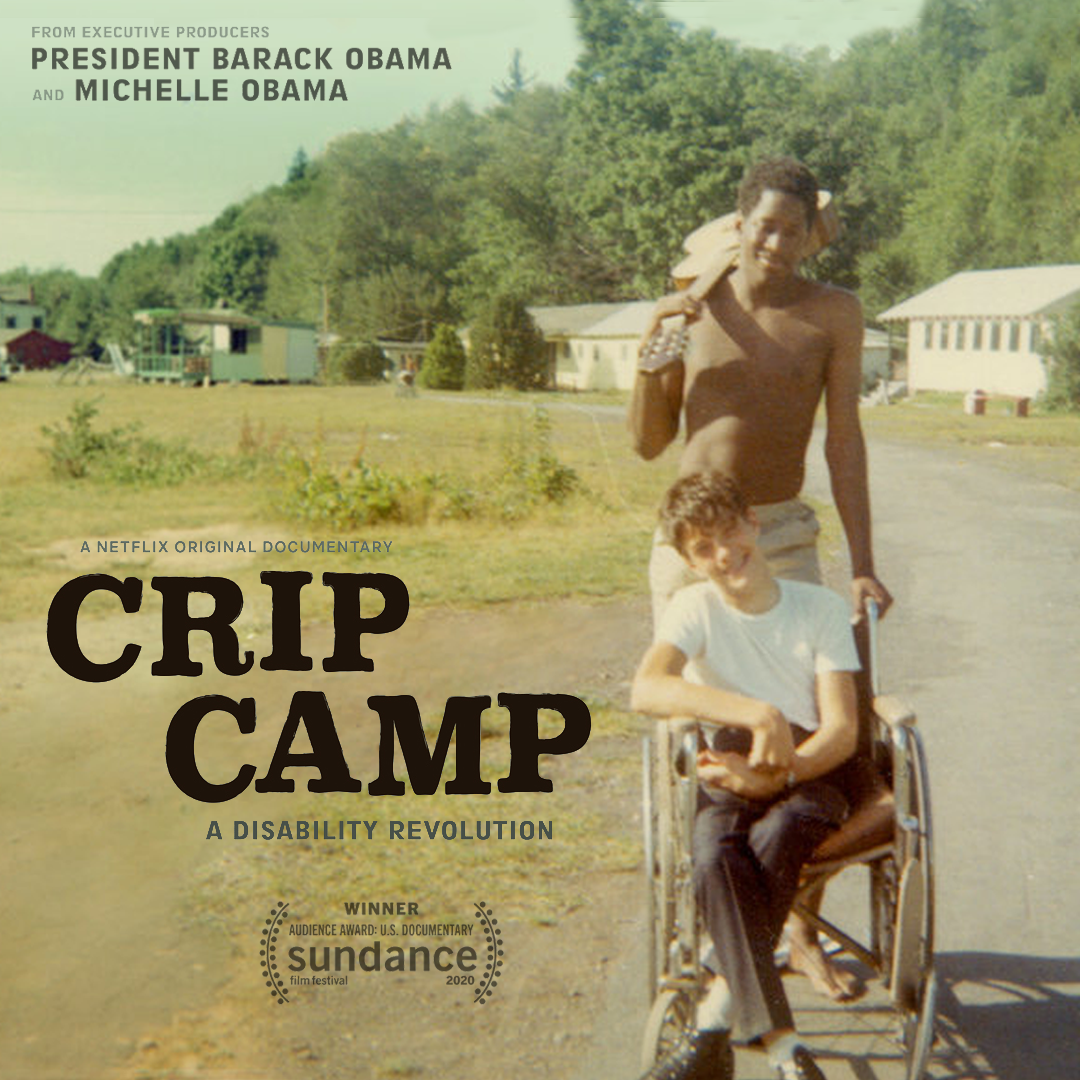

The documentary Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution (2020) uses a combination of footage from the early 1970s and recent interviews to profile Camp Jened, a camp in the Catskills for people with disabilities. The documentary follows the campers as they leave Camp Jened and become active in the disability rights movement, fighting for equal rights as they engage in picketing and civil disobedience. The trailer for Crip Camp packages the documentary as a motivational story of people with disabilities who are ultimately able to overcome the barriers of a world that often excludes them. In this essay, I am interested in the ways that the disability rights movement and the Civil Rights movement converge in the trailer. Intermingled with clips of the primarily white campers are a number of images that reflect Black support of disability rights, including able-bodied Black counselors at the camp and references to the contributions of the Black Panther Party to the disability cause. While the trailer does incredibly important archival work presenting the trajectory of an often overlooked, understudied movement, it does so by perpetuating the problematic disability-race analogy. The Crip Camp trailer relies on sound and images that echo the Civil Rights movement, suggesting that the disability movement needs to borrow from other activist projects to articulate itself. Further, a narrative framed by the Civil Rights movement analogizes race and disability, obscuring the existence of people of color with disabilities and inaccurately suggesting that the Civil Rights movement has been an unmitigated success.

Within the Crip Camp trailer are many images, sounds and symbols which reflect the Civil Rights movement. When the trailer transitions between showcasing Camp Jened and focusing on disability activism, one of the narrators, a white woman with a disability, says, “We needed a Civil Rights law of our own.” This statement is striking, conveying the idea that people with disabilities must borrow language from the Civil Rights movement to express the goals of their own movement. The phrase “of our own” suggests that the disability rights movement emerged only after the Civil Rights movement established a pathway for other social change, a historical inaccuracy which Angela Frederick and Dara Shifrer note. After this statement, the screen immediately shifts to an image of the Black Power fist, which is associated with Black pride and solidarity. Later in the trailer, the Black Power symbol reappears on the shirt of a white woman in a wheelchair. The recurrence of this symbol reflects a very clear choice in the design of the trailer to frame the disability activist narrative with the Black activist narrative. This blending of disability and Civil Rights occurs in auditory content as well. Images of white people with disabilities picketing and demonstrating are presented with gospel music in the background. The gospel music is one example of the way this trailer deploys iconography and sounds from the Civil Rights movement. The trailer also explicitly references the Black Panther Party, describing how the Panthers would provide people with disabilities hot meals. This blend of content associated with the Civil Rights movement creates the impression that the disability movement cannot be understood by the general public except through the lens of another activist movement.

The intersection of race and disability has become an important academic concern in recent years. For instance, Frederick and Shifrer show how analogies about race often depend on language that uses disability designations. Terms such as “color-blind racism” or “post-race paralysis” are often used to describe the pervasive impacts of post-Civil Rights racism (205). Frederick and Shifrer argue that this use of “damage imagery” in the form of referencing blindness and paralysis is problematic because it marginalizes people with disabilities as the “ultimate other” (205). By using language associated with disability to describe terms related to racism, disability becomes inextricably linked to the moral failing of racism. To be more specific, in the example of “color-blindness,” visual impairment becomes a metaphor for a deliberate mechanism that upholds racism (206). Moreover, the contemporary race-disability analogy moves beyond the use of disability metaphors in racial language. In her opinion piece, Lutisha Doucette, a black woman with incomplete quadriplegia, draws comparisons between her experience being in a wheelchair to that of a black person living in a pre-Civil Rights era of segregation. Doucette describes being forced to enter buildings through side doors and being placed in back corners of restaurants, saying that these experiences “conjure the historically painful specter of racial segregation.” These examples of the disability-race analogy in language and writing show that the Crip Camp trailer’s presentation of a similar analogy is founded in a very common practice. While the trailer no doubt intends the analogy as uplifting, progressive, and feel-good, I argue that the analogy has a much darker underside and in every case the disability-race analogy has been normalized, creating an audience which is primed to accept it without question.

While I am not alone in my skepticism about the disability-race analogy, the linking of these two identity categories has a long legacy. In his 1966 essay, “The Right to Live in The World,” Jacobus tenBroek uses the recent passing of The Civil Rights Act of 1964 to argue for the legal inclusion of people with disabilities, focusing on issues of access such as guide dog legislation (854). TenBroek capitalizes on the progress made in Civil Rights to advocate for disability rights, famously comparing race and disability in his statement, “as with the black man, so with the blind. As with the Puerto Rican, so with the post-polio. As with the Indian, so with the indigent disabled” (851). In grouping these categories of people, tenBroek suggests that race and disability are the same and thus require similar legal protections, an oversimplification of the many complexities which distinguish the requirements for racial inclusion as compared to disability inclusion. TenBroek’s analysis of The Civil Rights Act and the need for a similar legal framework for disability rights calls back the phrase from Crip Camp with which I began my analysis: “We needed a Civil Rights law of our own.” Despite being filmed half a century later, rhetoric which draws parallels between legal frameworks associated with race and disability remain pervasive. Moreover, a comparison of The Civil Rights Act and the legal needs of people with disabilities glorifies The Civil Rights Act as the ultimate goal, therefore obscuring its failures.

While there is certainly a strong Black presence within the trailer, there are almost no Black people with disabilities presented within the archival footage or in the personal testimonies. The lack of representation of people of color with disabilities presents the disability rights movement as primarily a white struggle, and the role of Black people as one of support. In the first section of the trailer, there are multiple images which feature a Black counselor working with a white camper. The image that stands out to me was one in which a Black counselor spins a white man in a wheelchair, helping him dance. Another image features a Black man pushing a white man with disabilities in a wheelchair during a protest, with a voice in the background saying, “The status quo was not what it needed to be.” The repeated imagery in which Black people are seen physically supporting white people by pushing their wheelchairs not only racializes the disability rights movement as a white movement, but plays into the dominant depiction of the disabled body as white.

“The repeated imagery in which Black people are seen physically supporting white people by pushing their wheelchairs not only racializes the disability rights movement as a white movement, but plays into the dominant depiction of the disabled body as white.”

Among current disability scholars and activists, the minority model or social model is often used to discuss conceptions of disability as an identity. Disability activists constructed the model minority framework of disability during the disability rights movement (Frederick and Shrifrer 201). Standing in opposition to the medical model of disability, the minority model argues that disability is produced by societal discrimination (201). The presentation of Camp Jened as a small utopia clearly reflects the minority model of disability. Black and white images of a metro and staircase establish the idea that the barriers that prevent equal access for people with disabilities are created by society and located externally. While this model can be helpful, Frederick and Shifrer argue that it has been racialized in a way which focuses on the experiences and needs of white, middle class disabled people, a phenomenon clearly reflected in the imagery cited above from the Crip Camp trailer (201). Recall the images I mentioned previously about the Black able-bodied camp workers pushing the wheelchairs of the disabled campers. Amidst a perfect representation of the idealized world for a person with disabilities, the experience of the white camper is central, while the Black presence is one of secondary support.

The narrative structure of the trailer follows a traditionally inspirational story arc: beginning with an idealized presentation of Camp Jened, then introducing the conflict and fight for equality, and ending with a depiction of people with disabilities as triumphant and strong. The moral of the film’s trailer is that people with disabilities can overcome adversity. The shifts in music and sound that accompany the images and videos effectively structure this story as inspiration. The trailer opens with an upbeat song that repeats “freedom, freedom.” The lyrics are accompanied by footage from Camp Jened, in which we see images of picnics, fields, guitars and people singing and dancing. Camp Jened is portrayed as a utopia for people with disabilities, where the combination of music, nature and community creates a lifestyle unparalleled by anything which exists in the larger world for people with disabilities. The shift away from Camp Jened is accompanied by a change in music, as the song ends and the tone becomes much more somber. Single, low notes overlay images of children in bleak institutions. However, the tone shifts once more: images of hope and fast gospel-like music uplift the tone once again, as the people with disabilities are shown overcoming the barriers of institutional power and fighting for political and social equality. The clearly defined three-phase narrative arc of the trailer—from utopia to oppression to victory—clearly presents the disability rights movement as a triumphant one and, by association, the Civil Rights movement as equally successful.

The triumphant tone and structure can be characterized as “inspiration porn,” a term used to describe representations of disability in media in which disadvantage is overcome for the pleasure and benefit of the viewer (Grue 838). In creating the three-part narrative I describe above, the trailer does not encourage a comprehensive understanding of what it means to exist as a person with a disability. Jan Grue defines inspiration porn in part as that which obscures reality by promoting a single story and excluding any details which might “disrupt the fantasy” in which disabled people overcome all the odds (842). Not only does the Crip Camp trailer misrepresent the experiences of white people with disabilities by presenting the disability rights movement as an inspiring success, but it also excludes presentation of the Black disabled identity as a way to preserve this fantasy of triumph.

Although the trailer focuses primarily on white people with disabilities, there are a few fleeting images of Black people with disabilities embedded into the footage. In one image, a Black person with a disability is sitting at a table with other campers, and in another a Black person with a disability can be seen in the background of an image of where a counselor is playing guitar in front of many campers. While these archival images exist within the trailer, they are few and far between. Moreover, there is no video footage of Black campers speaking, dancing, or laughing, as there are of the white campers. The contemporary interviews also lack the Black disabled perspective. The few images of Black people with disabilities are clearly anomalies within the trailer, unable to accurately portray anything substantial about the Black disabled experience. In choosing to exclude video footage and personal testimony from Black campers and activists, the trailer makes a very explicit choice to focus on the white disabled narrative.

By its very nature, a trailer is created with the intention to draw in viewers; the target audience of a film drives the design of any trailer. The Crip Camp trailer is no exception. While we might applaud these filmmakers for showing us an image of empowered people with disabilities, I argue that the trailer also reflects the kinds of stories that able-bodied people want to see about the disabled—stories of struggle, perseverance, and triumph. The trailer’s presentation of the disability rights movement through the lens of the Civil Rights movement facilitates the problematic exploitation of people with disabilities to create uplifting, feel-good stories targeted towards able-bodied people. In aligning the movements for racial justice and rights for the disabled, the trailer implies that both the Civil Rights movement and disability rights movement are stories of success. Further, the documentary fails to emphasize the unique struggles that people of color with disabilities experience. We get the sense that these filmmakers believe that an intersectional approach to understanding disability is not what the presumptively white, able-bodied audience desires. Moreover, the implicit racial bias of the filmmakers may have contributed to their analogizing of disability and race. Frederick and Shifrer summarize a study conducted in 2014 which found that white blind people draw analogies between their experiences and those of racial minorities, while blind people who are also people of color do not draw the same comparisons (204). The nexus of race and disability is clearly a complicated and fraught one. However, based on Frederick and Shifrer’s research, the analogy between the two is primarily a white phenomenon. With that in mind, it makes sense to read this trailer’s presumed audience as one that is not only able-bodied, but also white, and one that ultimately indulges in conceptions of disability as analogous to blackness.

In other words, the trailer’s design does not promote an intersectional evaluation of disability and race. In obscuring the experiences of Black people with disabilities, the trailer promotes a “single-axis framework,” the paradigm that Kimberlé Crenshaw critiques in her famous work defining intersectionality (139). Crenshaw uses a legal framework to uncover the experiences of discrimination that Black women face, arguing that they are not products of the sum of racism and sexism, but of an intersectional experience which is unique to the Black woman’s identity (140). Crenshaw summarizes a few key cases in which Black women are unable to file for discrimination based on race because the court will not allow their experiences to stand in for those of black men or of white women, the two groups protected under existing law (147). In a similar fashion, ameliorating the effects of the adversities faced by white people with disabilities will not necessarily ameliorate the effects of adversities faced by black people with disabilities. Moreover, the implicit reference to racism through language and imagery associated with the Civil Rights movement does not justify the lack of representation of Black people with disabilities within the world of the film, as this intersectional identity is not produced by the sum of race and disability discrimination. It’s worth noting that, after the introductory footage, the first frame that the trailer cuts to reads, “from Executive Producer President Barack Obama and Michelle Obama.” This frame solidifies the film as a racially inclusive, culturally progressive item. References to the Civil Rights Movement and the publicization of the trailer’s affiliation with the Obama legacy serve as covers which mislead the viewer from recognizing the absence of an intersectional approach to disability rights within the content of the trailer.

The disability rights movement is not the first U.S. social movement to be conflated with the black Civil Rights Movement through analogy. In similarly problematic ways, the Civil Rights Movement provides context for many other activist movements, such as second-wave feminism and LGBTQ movements (Frederick and Shifrer 203). Frederick and Shifrer attribute the widespread use of the race analogy to the success of the Civil Rights movement. By perpetuating this race analogy, whether in the Crip Camp trailer or in other texts and films that analogize the fight for racial justice to another social movement, we neglect to take intersectionality into account, obscure the experiences of those whose identities overlap more than one category, and offer simplistic and misleading historical narratives that imply we are much further along in racial justice than we actually are.

Works Cited

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” The University of Chicago Legal Forum, vol. 140, no. 1, 1989, pp. 139-167.

Doucette, Lutisha. “If You’re In A Wheelchair, Segregation Lives.” New York Times, 17 May 2017.

Frederick, Angela and Dara Shifrer. “Race and Disability: From Analogy to Intersection.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, vol. 5, no. 2, 2019, pp. 200-214.

Grue, Jan. “The Problem With Inspiration Porn: A Tentative Definition and a Provisional Critique.” Disability and Society, vol. 31, no. 6, 2016, pp. 838-849.

Newnham, Nicole and James Lebrecht, directors. CRIP CAMP: A DISABILITY REVOLUTION | Official Trailer | Netflix | Documentary. YouTube, 11 Mar. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=XRrIs22plz0.

TenBroek, Jacobus. “The Right to Live in the World: The Disabled in the Law of Torts.” California Law Review, vol. 54, no. 2, 1966, pp. 841-920.

Lily Coll is from Bethesda, Maryland. She studies public health and is majoring in women, gender, and sexuality studies with a minor in anthropology in the College of Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.