"I am Taiwanese!"

A Silent Cry for Taiwanese Identity in Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s A City of Sadness

Yeetang Kwok

READING THE VISUAL

— — —

In 1945, the defeat of the Japanese Empire in World War II reordered politics across Asia. Tokyo lost control of territory ranging from Burma, on the doorstep of British India, to Sakhalin Island, near Siberia. Japan’s colonial crown jewel, the island of Taiwan, set between Okinawa and the Philippines off China’s southeastern coast, had been ruled from Tokyo for fifty years; control was transferred to Nationalist China and its ruling Kuomintang Party led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, the internationally recognized government of China after World War II. When war-weary Chinese armies arrived on Taiwan from the Mainland in 1945, they found a place that was, on paper, part of China, but felt more like foreign territory.

Its people were a blend of Japanese and European colonizers with Han Chinese fishermen and farmers (mostly Hoklo and Hakka whose ancestors fled the mainland centuries ago), as well as aboriginal islanders. Over decades of estrangement and colonization, Taiwan developed a distinct brand of Chinese culture. They spoke Taiwanese and other regional dialects more readily than Mandarin, and incorporated Japanese customs into their daily lives. Within a few months of the Nationalist government’s arrival, as a result of linguistic and ideological differences and the Nationalist mismanagement of the island, tension between the local population and newly arrived Mainlanders simmered. The tension came to a head on February 28th, 1947, when the Taiwanese people revolted against the Nationalist police. Upwards of 20,000 died in the ensuing violence (Shih and Chen 92). The revolt became known as the February 28th Incident.

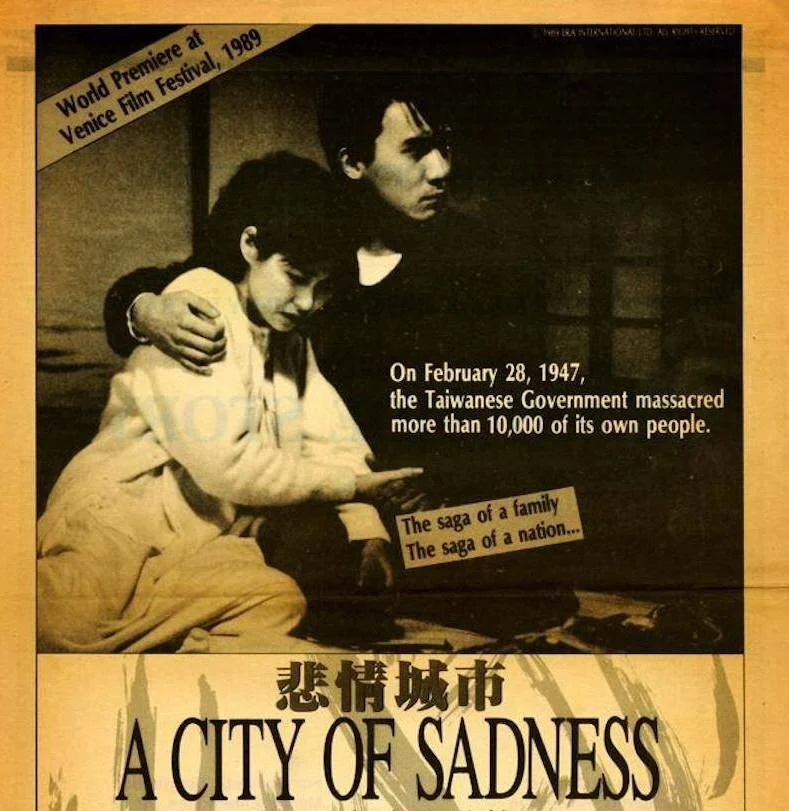

A City of Sadness, directed by Hou Hsiao-Hsien and released in 1989, was the first film to address the infamous February 28th Incident. The narrative, centered on the lives of three brothers, represents the Taiwanese perspective, from the initial Nationalist arrival in 1945 in the aftermath of Japan’s defeat, to the relocation of the entire Nationalist government to the island in 1949 after defeat at the hands of the Communists. Despite the optimistic outlook towards Chinese reunification at the beginning of the film, the arrival of the Nationalist Party proves to be just as painful, if not more so, than Japanese occupation. The war-worn Mainlanders bring with them summary arrests and executions, material exploitation, and rampant corruption. The Taiwanese perceive their Mainland Chinese brethren as betraying and silencing them. In the film, the character of Wen-Ching, the deaf-mute brother in a Hoklo-speaking Taiwanese family, whose attempts at communication are often met with misunderstanding, comes to represent the evolution of the Taiwanese identity more broadly.

The dinner scene that I analyze depicts the public sentiment in Taiwan shortly following the arrival of the Nationalist Party in 1945, during a period of time in which the Taiwanese are making an effort to assimilate into Mainland Chinese culture and identity. What strikes me immediately about this scene is how the dialogue emphasizes geographic locations. Words such as “Mainland,” “Japan,” and “homeland” appear throughout the conversation. The scene seems to tell us that where you come from matters because people discriminate between the Mainlanders, local Taiwanese, and the Japanese based on subtle differences. However, distinctions in geographic origin, especially between the Mainland and Taiwan, do not spur animosity in this scene. In fact, two of the guests sitting at the table are journalists from the Mainland.

(19:16) Dinner scene with two Mainland guests

The mood is cheerful with the guests sharing hearty laughs while mocking Japan’s flag. At the end of the dinner, the group joins in the singing of a patriotic wartime anti-Japanese song originating from northeast China. The refrain of the song speaks of return to a long-lost “homeland,” referencing the Chinese Mainland. That the local Taiwanese are singing a song from China’s northeast speaks to their connection to Mainland Chinese culture. Cheng-Feng Shih and Mumin Chen describe this attachment to Mainland culture as a primordial form of collective identity (10). Primordialism, they explain, is a collective identity that brings together groups based on “lineage, cultural characteristics (language, religion, tradition), or physical traits” (10). The Taiwanese people, despite speaking different dialects, still claim ancestry in Mainland China. Their subjugation under an alien Japanese regime only heightens their perceived kinship with the Chinese identity. Even when someone at the table complains about the disorganization of the Nationalist government, namely that the new Kuomintang governor of Taiwan is a “bandit,” the complaint is followed by a brief silence and then brushed aside by cheers to drink. If the brief pause is an implicit acknowledgement of his controversial statement, the rapid return to conviviality is a signal that the Taiwanese people, at least those depicted in the world of the film, are willing to put aside the early transgressions of the Nationalists in favor of a shared identity.

Despite feeling hopeful about the future under the Chinese Nationalists, there are embers of doubt smoldering underneath. Wen-Ching, the deaf-mute brother, embodies the silent unease of the Taiwanese people before the eruption of violence. As he waits to pick up skewers for his dinner friends, flickers of fire light up his melancholic face. He sits quietly as the people around him on the street start singing jovial folk songs. Despite not being able to hear, he understands the mood of the moment. The bright lights and animated movements in the room assure him that people are optimistic. Yet, his face remains wistful amidst loud laughter and his movements muted when others are vivacious. The contrast of his expression and movements to his surroundings projects uncertainty.

(21:51) A pensive look across Wen-Ching’s face as he waits for skewers

Although the Japanese were colonizers, their system of rule was orderly, if often harsh. They established a disciplined and efficient government and built modern infrastructure such as railways, electricity, and telecommunications; material standards improved from 1895 to 1945 (Mau-kuei 60). The Japanese departure, even if not publicly mourned, still imparts a sense of loss. Since it is not patriotic to commemorate the Japanese, those who do have to keep it to themselves. They also remain muted about their displeasure with the newly arrived Nationalist government, hoping that time will mend their initial differences. Therefore, Taiwanese people experience at once cautious optimism and silent opposition, sentiments that are difficult to put in words but show through in Wen-Ching’s somber expression.

One hour and a half into the film, simmering discontent with the Nationalist government boils over into violence between the Mainlanders and Taiwanese. In this later scene, Taiwanese men armed with pickaxes attack people speaking Mainland dialects near a bus station. Painful screams from the victims and vengeful shouts from the perpetrators fill the background. When the mob arrives on the bus, they interrogate Wen-Ching about his origins. Wen-Ching, despite being deaf, understands the gang’s motive and mutters in response, “I am Taiwanese,” the only line that he speaks in the film. However, even after saying that, the mob does not understand and proceeds to ask in Japanese if he is from Japan. Receiving no discernible response, the mob would have hacked him with their pickaxes had his friend not intervened on his behalf. I argue that the emergence of a distinct Taiwanese identity is apparent in this scene. Wen-Ching utters his only line in the film, “I am Taiwanese,” out of urgency and panic; it is a necessary phrase if he wants to escape the debacle. Early in the film, relations between Mainlanders and Taiwanese are cordial. However, by this point in the film, one’s geographic origin can mean life and death.

(1:34:06) A Taiwanese mob assaults Wen-Ching on the bus

This scene of the film parallels the February 28th Incident, in which reactions against police violence against a cigarette vendor erupted in violent riots. When the news got out, Taiwanese people across different cities marched onto streets and took control of government buildings and police stations (Morris). Pent-up frustration from drastic inflation, a broken justice system, and second-class treatment led many to take their anger out on Mainlander civilians. Eight days later, on March 8th, Nationalist soldiers landed in Taiwan to quell the rebellion. Numbed by the cruelty of war against the Japanese, these soldiers fired into crowds and killed thousands of civilians as reprisal, while death squads targeted professionals, intellectuals, and other active or potential political opponents (Morris). The revolts were utterly crushed within days. Amidst these revolts, the Taiwanese identity arises out of an urgent will to survive, in much the same way as Wen-Ching's cry of “I am Taiwanese!" It only emerges under the oppression of the new regime and the onslaught of the Nationalist army. In this scene of Hou’s film, hope for a united Chinese identity in Taiwan crumbles before our eyes with each swing of the pickaxe.

The awakening of a distinct Taiwanese identity during the February 28th Incident accentuates the suppression and pain of the Taiwanese people. Their pleas for self-determination were not only left unanswered but resulted in further persecution. In the later period of Japanese colonial rule, Taiwanese elites were given more power in local politics (Chu and Lin 109). Those elites, often lawyers, doctors, and intellectuals were educated in Japan and familiar with liberal ideas from the West. Yet, even as they worked to gain political powers in the colonial government, including parliamentary representation in Tokyo, they did not do so under a coherent Taiwanese identity (Chu and Lin 108). They thought of themselves as Japanese subjects of Han Chinese heritage. When the Japanese surrendered the island to the Chinese Nationalists in 1945, the local Taiwanese elite thought they would finally be treated as equals. They hoped to achieve democracy and modernize Taiwan alongside the Chinese Nationalist government. Instead, the Nationalist government installed Mainlanders to political posts while ignoring mistrusted local elites, seen as tainted by their association with Japan. The realization that they were to endure yet another authoritarian regime clashed sharply against the local elites’ liberal ideals and crushed their hopes for self-determination. This disillusionment after optimism is one part of the shared “sorrow” of Taiwan.

“The realization that they were to endure yet another authoritarian regime clashed sharply against the local elites’ liberal ideals and crushed their hopes for self-determination. This disillusionment after optimism is one part of the shared ‘sorrow’ of Taiwan.”

The Taiwanese experience depicted in this film bears some similarity to W.E.B. Du Bois’s famous notion of “double consciousness.” Du Bois claims that the acquisition of a more coherent national consciousness (in Du Bois’s case, as American; in Hou’s case, as Taiwanese) forces the individual to understand the true weight of oppression (12). As the newly educated black Americans gain a “dawning self-consciousness, self-realization, self-examination,” they begin to realize that the black American “must be himself, and not another” (12). A sense of hopelessness arises when they become aware of just how difficult it is to create a healthy identity while carrying the “dead-weight of social degradation” (12). In much the same way, the Taiwanese intellectuals, who recently shed their colonial mindsets and wished to finally pursue self-determination, are faced with violent suppression. Their knowledge of liberal democracies has accentuated their disenfranchisement. Hou captures this voicelessness in Wen-Ching’s character as he faces violence. On the bus, he understands the situation but cannot speak out or defend himself. His other form of communication, writing, is too slow for such a volatile moment. As a result, his disability puts him at the mercy of others. Even when he does try to speak, he is misunderstood or ignored. Wen-Ching’s eyes, normally serene, seem frantic at this moment due to the agony of trying to speak but not being able to. His body language is constricted; there is suffocating powerlessness in his movements. Wen-Ching’s embodied response enacts the silencing of the previously active intellectual milieu after the February 28th Incident.

Directly following his arrest due to the failed communication on the bus, Wen-Ching is sent to prison and the following scene depicts the effect of this silencing on a personal level. Due to his association with dissident scholars, Wen-Ching is thrown into a jail cell with three others. The overarching tone is one of uncertainty and powerlessness. The narrow frame showing the prison door and low ceiling convey claustrophobia. The hurried footsteps of the guards contribute to the smothering despair of the room. Two men in the same cell are dragged out to the firing squad. The inmates are well dressed in collared shirts and bookish glasses, typical of the local elites at the time. In fact, the Nationalist government targeted thousands of these lawyers, doctors, and intellectuals who made up the respected professional class (Chu and Lin 112). Wen-Ching, even though he cannot hear the gunshots, seems to understand the fates of the two men before him. He stares into the hallway, wondering what will happen to him. His calm resignation accentuates the loss of agency in this scene.

(1:45:40) A group of soldiers leading Wen-Ching down a corridor

The sorrow of this scene comes from the fact that no matter what he says or does, he is at the mercy of others, rendering him an apt embodiment of the experiences of Taiwanese families following the February 28th Incident, when the government initiated martial law. Instead of giving the locals more voice after the riots, the Nationalist Party decided to strengthen its grip on the island, instituting laws restricting political activity, speech, and movement (Morris). Newspaper articles were censored by the government. Military police spied on letters and phone calls. Family members disappeared at random. Some were killed, others imprisoned for long sentences, others beaten and released. This period of martial law, known as “White Terror,” lasted from 1949 to 1987 (Morris). A few moments later in the film, guards come and announce Wen-Ching’s name. With no protest, he is then escorted down a narrow hallway lined by iron bars, disappearing into the far end of the frame. Is he next in line for the firing squad, or to be released? Wen-Ching’s uncertainty and fear in the jail cell reflect the trauma of repression in the aftermath of the February 28th Incident.

The February 28th Incident and the subsequent White Terror were pivotal events contributing to the “sadness” of Taiwanese identity. Using this term to describe their identity appears not just in the title of the film but also in popular consciousness. The President of Taiwan from 1988 to 2000, Lee Teng-Hui, called the powerlessness of the Taiwanese people under alien regimes the “sadness of being Taiwanese” (Mau-kuei 60). Others have dubbed the island the “orphan of Asia” (Shih and Chen 95). Indeed, the shared “sadness” and violent repression of the Taiwanese people have helped carve a constructed collective identity, an identity that stands apart from the Mainland Chinese. According to Shih and Chen’s understanding of structuralism, common destiny or shared deprivation of rights (rather than ethnicity or shared genetics) is prerequisite to the formation of a cohesive identity (10). In fact, the native Han Taiwanese population has not always been united. Since their arrival to the island in the early 17th century, after fleeing poverty and war on the Mainland, the two predominant ethnic Han groups, Hakkas and Hoklos, among many other subgroups of clan and tribe, have faced internal conflict (15). It was through common opposition to Dutch colonization in the mid 17th century and to Japanese colonization in the 19th century that the Han Chinese groups became more united. The new Chinese Nationalist regime was different from the Dutch and the Japanese in that they were not initially seen as alien by the Han Taiwanese. However, as the regime began taking up the posts of previous outside rulers and repressing the local population, the primordial association based on ethnic origin began to fade in favor of a structuralist identity based on shared suffering.

Despite the sorrow of the Taiwanese condition, Hou’s film suggests that the Taiwanese persevere through tragedies with a quiet dignity. The prisoners, even as they are uncertain of their fates, inhabit a calm disposition. Their faces are somber, but not flustered. They move calmly and gently, as opposed to the guards, who move with a militaristic cadence. Before each person leaves the jail cell, the group embraces each other and says their goodbyes. This camaraderie between the prisoners counters the harshness of the military police, symbolizing the formation of a collective Taiwanese identity even under a severe Nationalist regime. In the background, we hear light singing of a mournful Japanese song, a defiant act given the Nationalists’ hatred of the Japanese. When Wen-Ching and the other prisoners leave their cell, they put on dress shirts and don their glasses as if leaving for work. Even in death, they wish to preserve their dignity as intellectuals and professionals. This act also represents the Taiwanese people who, having been forced into submission, go on with their lives despite constant fear.

(1:43:55) Two men putting on shoes before being led out of the cell

In fact, the prison scene suggests that the silence of Wen-Ching is a strength, not a disability. Save for some quiet singing and a few words exchanged, the scene is silent. For the first time in the film, Wen-Ching does not stand out as a deaf and mute person. Others in the cell have become more like him, unable to speak out but able to persevere in silence. They write with whatever they can find, including their own blood. Facing injustice, silence is a form of resistance. Thus, the Taiwanese identity is not just comprised of sorrow, but also a silent dignity that carries them through the White Terror.

Elites who were silenced in the 1950s re-emerged in the 1980s to become leaders of the democracy movement in Taiwan (Chu and Lin 120). Despite thirty years spent in a repressed state, these activists and intellectuals continued seeking self-determination with the same vigor as their predecessors under Japanese rule and during the onset of Nationalist rule. They finally succeeded when then-president Chiang Ching-Kuo lifted martial law in 1987 and allowed the formation of opposition parties. During those four dark decades before, Taiwanese identity took a drastically different turn from its Chinese origins. First was the openness to the Nationalists in 1945, followed by quiet unease of the first months, as seen on Wen-Ching’s brooding expressions during a lively dinner. Exemplified by Wen-Ching’s only line, “I am Taiwanese,” the Taiwanese identity began to diverge from the Nationalist Chinese in 1947 after two years of misrule and eventual military crackdown. It then matured under the shared anguish of living in silence and fear, transforming into a structuralist Taiwanese identity. Wen-Ching’s silence does not merely represent the “sadness” of Taiwanese identity, it reminds us of the tenacious dignity of an identity based on suffering.

Works Cited

Chu, Yun-han, and Jih-wen Lin. “Political Development in 20th-Century Taiwan: State-Building, Regime Transformation and the Construction of National Identity.” The China Quarterly, vol. 165, 2001, pp. 102–29. Crossref, doi:10.1017/s0009443901000067.

Du Bois, W.E.B. “Of Our Spiritual Strivings.” The Souls of Black Folk, Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 7–18.

Hsiao-Hsien, Hou. “A City of Sadness (1989).” YouTube, uploaded by Just Relax, 12 Nov. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Aolv8k99ZOU&t=1s&ab_channel=JustRelax.

Mau-kuei, Chang. “On the Origins and Transformation of Taiwanese National Identity.” China Perspectives, no. 28, 2000, pp. 51–70, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43392897.

Morris, James. “The 228 Incident Still Haunts Taiwan.” The Diplomat, 27 Feb. 2019, thediplomat.com/2019/02/the-228-incident-still-haunts-taiwan.

Shih, Cheng-feng, and Mumin Chen. “Taiwanese Identity and the Memories of 2–28: A Case for Political Reconciliation.” Asian Perspective, vol. 34, no. 4, 2010, pp. 85–113. Crossref, doi:10.1353/apr.2010.0007.

Yeetang Kwok is from Toronto, Ontario, Canada. He studies math and economics with a text and traditions minor in the College of Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.