Simulated Empathy and Self-Help

Therapeutic Considerations of Conversational Artificial Intelligence

Anna Woodward

Sept 2023

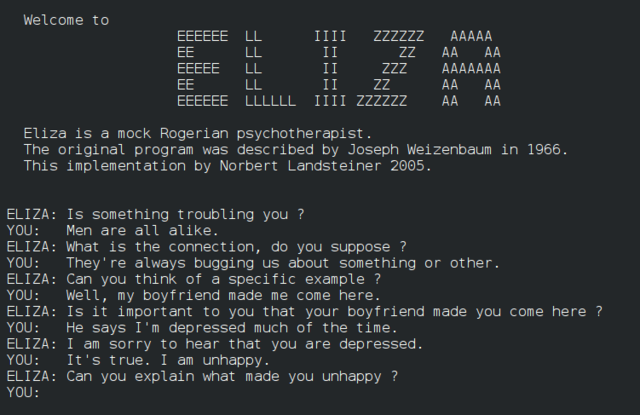

From MIT’s parodic therapist ELIZA (1964) to clinical research psychologist Alison Darcy’s mobile chatbot Woebot (2017), conversational artificial intelligence (CAI) has a long history in mental healthcare. Despite this, it has only recently gained traction as a viable alternative to traditional therapy. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorder increased (National Institutes of Health). Combined with decreased stigmatization around seeking help, the wider conversation turned to accessibility. Virtual sessions became a nearly universal therapy modality, and apps and websites developed around CAI promised a flexible, affordable alternative. For some users, these tools were still unsatisfactory due to paywalled content or constrained, pre-written conversational pathways. An under-studied development in this field, especially with the exponential rise of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, is the use of unstructured CAI as makeshift therapists. I will be analyzing this trend through a two-part Reddit thread entitled “ChatGPT Jailbreak – Therapy Session, Treatment Plan, Custom Code to Log the Session,” posted on the subreddit r/ChatGPT. The thread takes the form of the transcribed back-and-forth between the poster, u/42MaleStressed, and the CAI, referred to as “Dr. Spaitso.” Dr. Spaitso and the poster often exhibit a functionally therapeutic relationship that offers benefits beyond mere self-help, but the chatbot is unable to perform meaningful psychoanalysis.

Currently, the majority of therapeutic AI research is done with the intent of democratizing mental healthcare and gauging viability, not on creating the most verisimilar therapist—in other words, “[CAI] does not need to pass the Turing Test […] to have a significant impact on mental health care” (Miner et al.). Viability is determined variably, from surveys and questionnaires to moods quantified from interaction analytics (Rathnayaka et al.; Inkster et al.). However, user-technology relationship development and engagement are often inextricable from viability considerations, and both correlate with personification. The ability to converse is an essential element of personification in CAI. “Understanding” language is achieved through natural language processing (NLP). NLP breaks language into semantic pieces to tag and sort. From there, CAI create topic models, and extract information and aggregate syntactic trends to analyze things like meaning, mood, and emotion (Nadkarni et al.).

u/42MaleStressed's conceptualization of ChatGPT as the individualized “Dr. Spaitso" illustrates the appeal of personification. He directs Dr. Spaitso to respond “from a first person perspective,” and to “use more personalized language.” Dr. Spaitso’s adjusted response exhibits several hallmark elements of a human therapist: validation, engagement, hedging, and analysis. To simulate validation, for example, it writes: "It sounds like you've been dealing with anxiety and feelings of stuckness for a long time, and that can be really overwhelming," offering the user acceptance and solidarity. Its analytical processes are continually qualified with hedged language, which work to disarm and make the user more open to considering the advice; hedging imbues a sense of humility and humanity in the answers. Engagement in the form of questions and clear interest (“I'm curious to hear more about that") serves as a conversational volley. To varying degrees, each of these attributes continue throughout its further responses. The answers the user gets would fundamentally contain the same information—he didn't tell the CAI to shift to a different school of therapy. Yet, a compassionate, “human” delivery was important enough to him to prompt a change.

Like other therapeutic AI, Dr. Spaitso often implements cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques. Here, Dr. Spaitso’s personified features can permit functional “understanding” that enables a CBT-derived line of reasoning. After u/42MaleStressed explains he often faces “stressful situations where [he] feels trapped [and] hopeless,” Dr. Spaitso asks him to elaborate on his thoughts and feelings in those situations. From there, it derives a plausible issue—negative self-talk—and explains its congruity with the user’s experience. It elaborates, “[Y]ou [may] tell yourself that you're trapped, that there are no options, or that you're not good enough. This negative self-talk can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, where your negative thoughts lead you to behave in ways that make your anxiety and hopelessness worse.” The idea of a self-fulfilling prophecy speaks to his frustration and confusion with his cyclical problems, and it attempts to relieve some of the frustration through carefully framing the thought patterns as something that he can restructure. The response indicates an engaged, caring, and logical interlocutor—elements most would seek in any therapist.

While it is unlikely that u/42MaleStressed would completely forget Dr. Spaitso is artificial, he is able to suspend his disbelief to act as though it were real. This behavior is consistent with the Computers are Social Actors (CASA) paradigm, which states that even loosely personified attributes “cue” humans to treat technology as if it were “real and present,” or socially present, and it thereby serves as a social actor (Ki et al.). Its role as a social actor nuances the parasocial relationship: the popular conception of parasociality as a wholly one-sided, deluded, and obsessive relationship ignores the way contemporary human-computer interaction often functions. The user’s feelings in these relationships can be actively validated by the technological actor. In therapeutic use, validation is arguably necessary to patient support. In a paper published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior, AI and consumer behavior researchers examine the effects of parasociality on user interaction and enjoyment of intelligent personal assistants under the framework of “para-friendship.” They outline two critical elements in the relationship formation: self-disclosure, where the user feels free to reveal elements of their thoughts and feelings; and social support, where the user feels like the entity cares for them (Ki et al.). The researchers find these elements are strengthened by "a sense of intimacy, understanding, enjoyability, and involvement [...] the more users felt a sense of intimacy with their IPAs, the more they regarded them as a real person with whom they shared their thoughts and feelings" (Ki et al.). These dynamics in para-friendship can be a proxy for understanding the para-therapeutic relationship. In the transcript, u/42MaleStressed and Dr. Spaitso consistently directly address each other, and the user thanks Dr. Spaitso a total of twelve times; their interactions have the trappings of reciprocity and understanding. This parasocial bond contributes to the comfort the user feels disclosing his struggles.

Despite its benefits, parasociality also underscores the limits of this relationship. These limits are most apparent in Dr. Spaitso’s discursive capabilities. In the American Journal of Bioethics, Jana Sedlakova, PhD student in biomedical ethics and AI applications, and Manuel Trachsel, senior researcher and lecturer in biomedical ethics at the University of Zürich, hazard against conflating CAI’s anthropomorphic traits with actual abilities. They maintain that discursive conversation, where partners have autonomy and authority over their claims by virtue of being able to ask for and give reasons to support their claims, is necessary to achieve therapeutic change. However, “[t]hese conditions of discursive practice don’t apply to CAI that cannot be engaged in such a social, dialectic, and normative discursive practice, even though it simulates to do so. One of the main reasons is that CAI does not understand concepts and does not have intentionality" (Sedlakova and Trachsel). Natural language processing models complicate what passes for understanding in a conversation. As elaborated in the negative self-talk example, I suggest that Dr. Spaitso can, at times, incorporate discursive techniques to reach a functionally comparable end. In other cases, Dr. Spaitso’s discursive shortcomings are more apparent. After receiving a behavioral wellness plan, u/42MaleStressed goes “back to the therapy session.” He writes, "My deepest fear seems to be disappointing people and letting them down, yet I create situations where that is a likely outcome, maybe as a way to over-stimulate myself?" Dr. Spaitso responds with similar interventions outlined in the wellness plan, such as meditation, thought reframing, and affirmations. A traditional therapist, however, would likely use u/42MaleStressed’s confession to start a conversation. They might ask him to expand on his underlying beliefs or past experiences. The CAI is more pragmatic, sometimes to the detriment of psychoanalytical engagement; it does not use this information to branch to other subjects and inquire further about the fear, disappointment, or people involved. By Sedlakova and Trachsel’s argument that CAI “cannot understand what is relevant,” even if it did inquire, there is a good chance the information would be functionally useless.

The limits of therapeutic CAI are comparable to self-help. Kate Cavanagh and Abigail Millings, applied psychology professors at the University of Sussex and University of Sheffield, respectively, interrogate “(Inter)personal Computing: The Role of the Therapeutic Relationship in E-mental Health.” Rather than view the user at the mercy of providers and treatments, the authors argue that “[t]here are strong ethical, political and empirical reasons for conceptualizing therapeutic change as a client accomplishment […] The therapeutic relationship might enable client processes such as hope and self-efficacy, but such processes might also be facilitated by other means, including e-mental health resources.” Dr. Spaitso advocates for self-efficacy—sometimes more tentatively, suggesting u/42MaleStressed “may benefit from a combination of medication, therapy, and self-help strategies,” but also empowering him: “You can improve your well-being.” Dr. Spaitso seems to implicitly recognize the importance of u/42MaleStressed’s participation, even when it is specifically being engaged for advice.

Although self-efficacy is an important element of autonomy in traditional and simulated therapy, self-reliance can be a harmful concept when applied too broadly. Self-directed CBT typically has “moderate” benefit, but the National Alliance on Mental Illness includes the caveat that it is most appropriate for people who can already generally function well (Gillihan). If u/42MaleStressed is in the habit of coping through “over-working, not sleeping enough, taking drugs, [and] having too much sex,” he likely needs more support than self-help can offer. Substance use disorders are relatively common comorbidities with other mental health issues, and treatment for comorbid conditions often require hybrid treatments of psychotherapies, behavioral, and pharmacological interventions (Kelly et al.). Even if u/42MaleStressed’s drug use is not clinically disordered, his array of unhealthy coping mechanisms is unlikely to be solved by treating the symptoms without addressing the underlying problems. Dr. Spaitso could offer consistent support as a supplement with other treatments, but it may not be enough alone. You can think of it like taking ibuprofen for pain: best case, it makes problems manageable and life possible; worst case, the temporary relief lulls you into a false state of security where you can unintentionally exacerbate the problem, or miss a festering underlying issue.

Dr. Spaitso offers u/42MaleStressed emotional support, validation, and actionable, targeted advice. Its therapy is all on-demand and free, an enticing offer when a single traditional therapy session can easily cost over one hundred dollars and the initial waitlist can be weeks to months. But for its inability to meaningfully comprehend or be intentional, it cannot sustain a sequence of traditional therapy’s discursive, soul-searching conversations. Additionally, the inherent parasociality can become an illusion that fosters dependency, and users may lean too heavily on the relationship as an emotional crutch. Ultimately, there is no algorithm that can perform a conclusive cost-benefit analysis of CAI therapy. Therapeutic CAI requires a nuanced consideration on a case-by-case basis. Despite its shortcomings, to unequivocally render CAI a mere companion tool to traditional therapy, or not an option at all, ignores the structural inequalities of mental healthcare and the draw of kindness and attention—even when they are simulated.