Diversity Commodified

Hollywood’s Racial Identity Crisis

Mallorie Goodwin

Sept 2023

Fig. 1: Grande crouched on the floor in her 7 rings music video.

For years, certain celebrity women such as Ariana Grande, Kim Kardashian, and Kylie Jenner have been routinely adopting the features of different ethnic groups under the guise of engaging with popular trends, particularly with features from the Black community. Despite how it may appear, this practice is not so innocuous and preys upon age-old stereotypes that surround Blackness. Anderson et al. write that “the overt objectification and dehumanization of Black people has a long history throughout the Western world,” manifesting through stereotypes such as the Jezebel, “an alluring and seductive African American woman who is highly sexualized and valued purely for her sexuality” (Anderson et al. 462). For non-Black women, who never experience the true gravity of such a caricature, posturing oneself closer to stereotypes of Blackness such as the Jezebel grants access to increased perceptions of seduction without any of the dehumanizing impacts. In doing so, they engage in a practice identified by Amber Jamilla Musser in “Specimen Days: Diversity, Labor, and the University” as the “commodification of diversity,” wherein an institution or individual engages with diversity so as to acquire it for cultural or monetary gain (Musser 2). By proxying themselves close to Blackness to commodify it, these women gain access to their preferred aspect of Black stereotypes without any of the harms, all while perpetuating these stereotypes, contributing to the harm Black women face as a result.

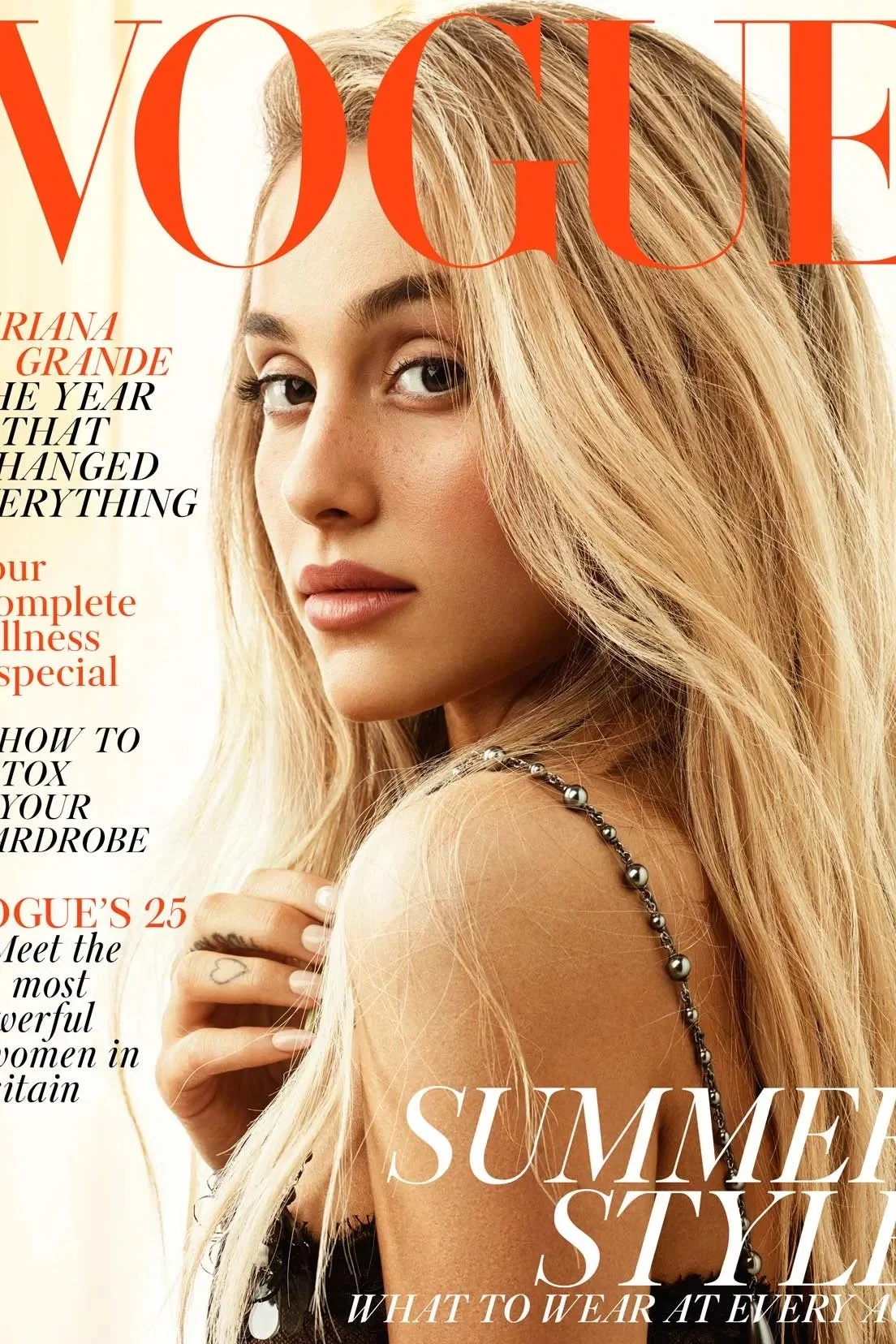

Ariana Grande routinely dons commonly understood Black and white characteristics as a way of indicating how she should be perceived in a particular setting. When Grande appears on the cover of Vogue, she has fair skin, blonde hair, and thinner lips—commonly understood elements of whiteness. Alternatively, in her sensual 7 rings music video, she imitates Black features and Black culture by overlining her lips, tanning her skin, wearing oversized earrings, and rapping.

Fig. 2: Grande on the cover of Vogue.

Relevant to the conversation about objectification is not just what Grande looks like in 7 rings as compared to on Vogue, but also how she looks in her music video compared to the cover of a prestigious magazine. As Grande sings, raps, and dances in 7 rings, she frequently contorts herself into unconventional positions—she arches her back like a cat, drops to all fours in a frog-pose, stalks on the ground, and more. While it is clear that these positions are meant to be sexual, what is also important is that these positions are animalistic. When Grande is on Vogue, this is not the case—she stands up straight and looks at the camera head-on, like a person. This comparison reveals that not only does Grande posture herself closer to Blackness when she is trying to appear sexual, but in doing so, she contributes to the trope of portraying women of color (or, in her case, a white woman dressing up as a woman of color) as animals. According to Anderson, this trope is something that has existed “throughout history” that was not just plainly racist, but also “a way of legitimizing racial discrimination towards [Black people]” (Anderson et al. 462).

By portraying Blackness in sexual music videos but whiteness on elite magazine covers, Grande supports and furthers an implicit connection between Blackness and sexuality and whiteness and grace. Furthermore, by engaging in animalistic behavior while she is portraying Blackness, she feeds into racist stereotypes that extend further to not just the sexuality of Black women, but their humanity. Both actions objectify Black women for personal gain, meaning that both are examples of the commodification of diversity (Musser 2).

Fig. 3: Grande crawls on all-fours in her 7 rings music video.

More blatant examples of diversity being commodified can be seen through the actions of the Kardashian-Jenner Family. The Kardashians and Jenners imitated Blackness for much of their careers when Black styles were highly popular, even going so far as to wear cornrows (Payne). Now that trends are changing and typical symbols of whiteness are beginning to reemerge, the Kardashians and Jenners are imitating whiteness with an ease that is akin to children playing dress up; they are removing their implants, dying their hair lighter colors, dissolving their lip fillers, and definitely not wearing cornrows. When Kim Kardashian wore Marilyn Monroe’s dress at the Met Gala, a classic symbol of American history, culture, and fashion, she had blonde hair and had undergone extreme weight loss, both stereotypical symbols of whiteness. Stereotypes about Black bodies date back at least as far as the slave trade, with the notable example of Saartjie Baartman, who was “displayed in a cage and wearing next to nothing,” so that Londoners could “gawk at her atypical…large buttocks and features” (Anderson et al. 461). Kim Kardashian’s extreme weight loss was not just a literal shift from one size to another, but also a figurative shift from one race to another, which is only solidified by the fact that her hair, facial features, and dress were more in line with standard images of whiteness.

Kim Kardashian and her sisters commodify diversity in a similar way as Grande, changing which race they portray depending on whether they want to appear sexual or classy. While the Kardashian-Jenner family may do its best to avoid accountability on the matter, the reality is that they, too, reinforce racist stereotypes against Black women, all so that they can be seen as increasingly sexual beings, while ignoring the harm that is perpetuated by their actions.

Fig. 4: Kim Kardashian wears cornrows (Payne).

All of the above is undoubtedly in line with Musser’s concept of the commodification of diversity (Musser 2). Musser describes her time at Washington University and how the commodification of her diversity “[conspired] to produce [her] as a specimen…a commodity, static and rare” by compartmentalizing her diversity so as to commodify it, ignoring the entirety of her personhood (Musser 2). Similar to how Musser’s university compartmentalized her diversity into neat and easily understood components, by reducing groups down to their trends, their facial features, or their bodies, Hollywood women objectify other women of color so as to make the diversity of women of color easier to commodify for personal gain.

What makes Musser’s perspective as a lens source especially relevant is how she highlights the institutional aspect of this phenomena, and how this can be extrapolated to other situations. Similar to how her employing university had institutional problems that allowed the commodification of diversity to be carried out by individual actors, these women are individuals that are the ones carrying out harms against Black women, but it is the institutions that support them that make their decision to portray themselves as Black women possible in their careers. With this established, it then becomes possible to say that the harms perpetuated against Black women by these women in Hollywood are not individual but institutional harms, and grave ones at that.

Fig. 5: Kim Kardashian wears Marilyn Monroe’s dress at the 2022 Met Gala (Segal).

By reducing women of color down to just their components and mixing and matching them whenever they please, these Hollywood women and the forces behind them reduce ethnic features themselves to hyper-sexualized trends. They make whiteness the canvas that these “trends” rest upon, asserting the notion that however popular an ethnic trend may be at a time, it is whiteness, ultimately, that is timeless. These long-held stereotypes continue to produce tangible harms in the lives of Black women. Anderson writes that frequent objectification has been found to be correlated with “contributing to the view that [the objectified] are less competent, less worthy of moral consideration and treatment, more responsible for being raped, and more deserving of maltreatment” (Anderson et al. 463). While these harms can be ignored by the women who perpetuate them, they cannot be ignored by those that experience them.

While there has yet to be any conclusive proof that the decision to imitate people of other races is a conscious one for these women, it can be said that their actions are not innocuous. No one can claim that this is akin to a game of dress up because they are playing dress up with people’s facial features. When the trends change or the dress code changes, these women can step back into comfortable white spaces without having to reckon with the difficulty experienced by women of color. Kylie Jenner will be able to imitate Blackness on Instagram while calling herself a “baddie,” but it is young Black women who will carry “badness,” in every sense of the word, with them when Jenner has moved onto a different race (Jenner). Women of color must continue to exist in the reality that these Hollywood women can step out of, and it is women of color that are left to deal with the fallout.