COVID-19 Meets Systemic Racism: Racial Disparities in Black and Hispanic Communities

David Bradford

#iamnotavirus

As the COVID-19 pandemic progresses, it reveals that racial minorities in the United States are more likely to be infected and suffer worse outcomes due to a combination of disparities in exposure, susceptibility, and access to proper healthcare—patterns that will become more defined and visible as we experience additional months of infections and deaths. My research focuses on how racial disparities are directly causing unequal COVID-19 infection rates in Black and Hispanic communities in the United States. I find that institutions historically designed to discriminate against minorities, such as housing, employment and healthcare, are worsening the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on minority communities today.

Following Quinn et al.’s investigations of disparities in exposure, susceptibility, and access to health care during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, I created a survey to gather research on how differences in COVID-19 exposure and treatment are disproportionately impacting minorities. The population surveyed consisted of 99 students and adults from Washington University in St. Louis and Chicago, Illinois, which limits the strength of disparity-related patterns that can be seen more clearly in very large, infected populations. There is also an overrepresentation of responses from minorities that could skew data, as the ratio of minority to White respondents is more than 2:1.

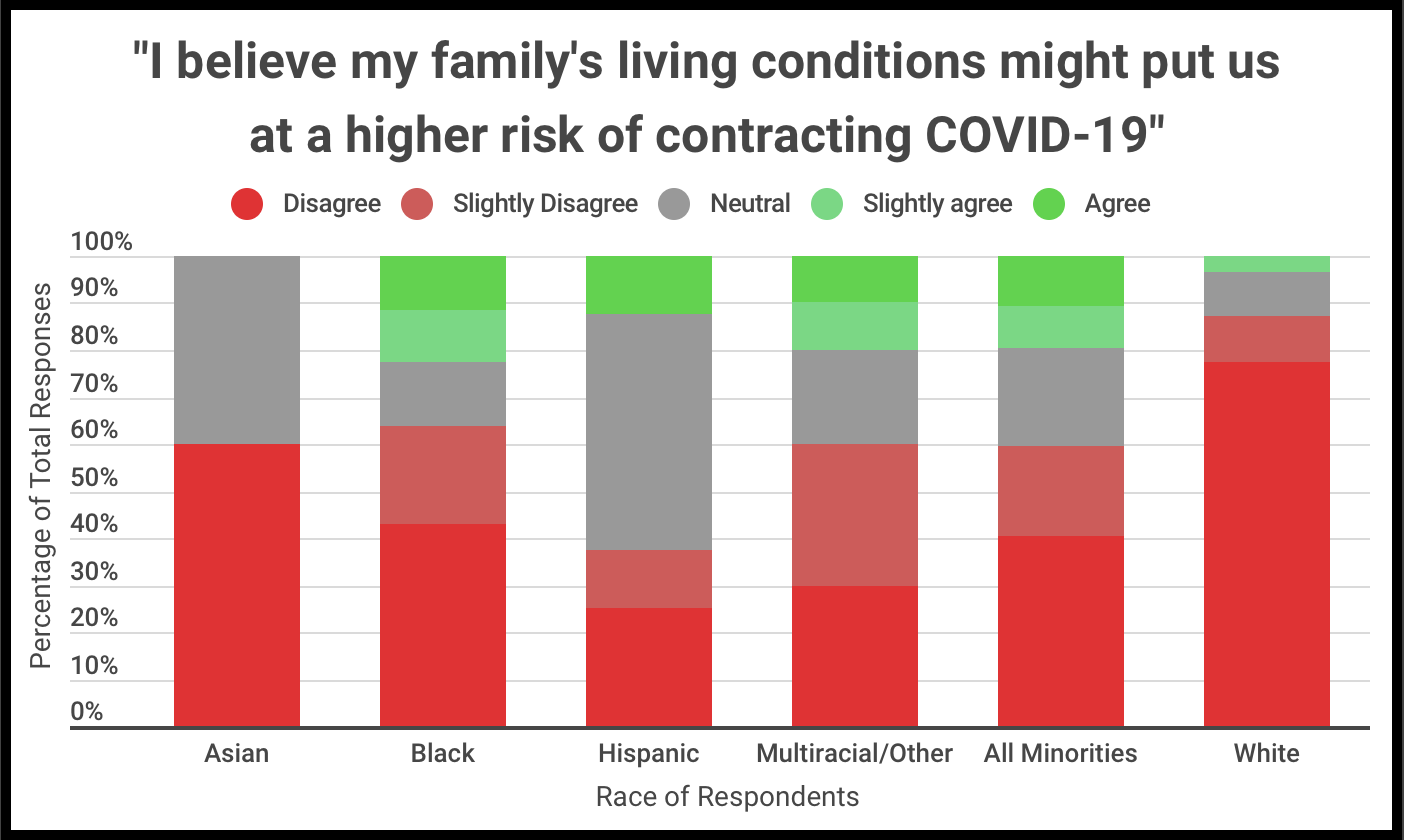

Both minority and White respondents had very similar proportions of responses to the first three questions regarding disparities in exposure based on living conditions (number of residents per household, whether or not a family member had a diagnosis or symptoms of COVID-19 in their household and whether or not their family lives in a major city). However, just 3% of White respondents live in an apartment building or take public transportation, compared to 23% and 13% of minority respondents, respectively. These findings suggest that minorities face a higher likelihood of being exposed to COVID-19 due to living conditions that make it more difficult to maintain a safe social distance from others at all times.

In order to scope how working conditions might contribute to disparities in exposure, I asked respondents to agree or disagree with a series of five questions related to the occupations of household members.

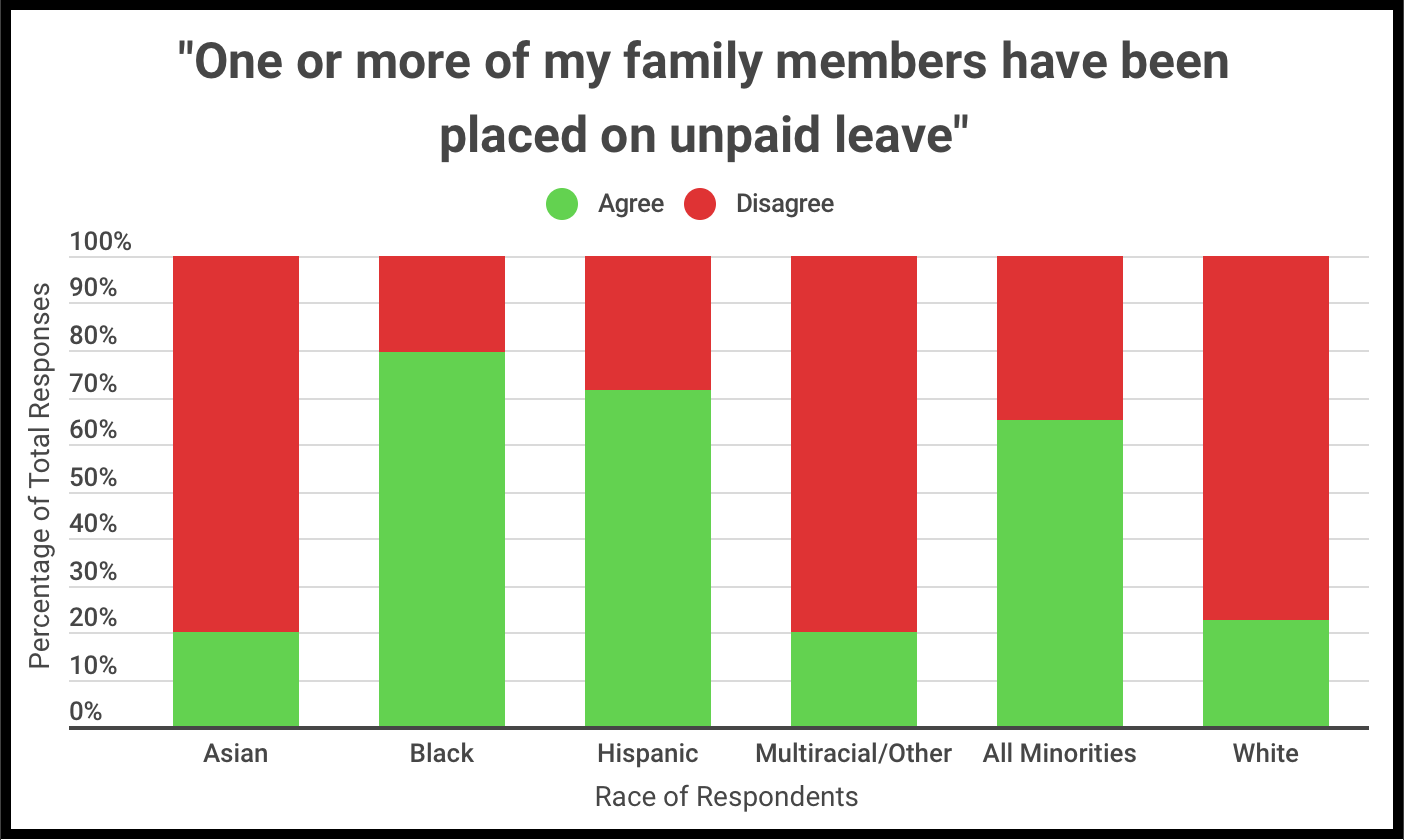

For both minority and White respondents, a majority of families have at least one or more family member that can work from home (remote workers) as well as one or more whose occupation can only be performed in the workplace (essential workers). However, 63% of minorities have one or more family members on paid or unpaid leave, compared to just 13% and 23% of White respondents, respectively.

This suggests that while most minority households have a combination of remote, essential, and/or furloughed workers, Black and Hispanic workers face a greater risk of being furloughed than White workers. Additionally, half of minority respondents have a family member with inadequate sick leave, which could negatively impact the family’s financial situation if forced to stop working or significantly impact the well-being of the community if they are forced to return to work while sick.

This situation is exacerbated by disparities in healthcare access and treatment: 25% of minority respondents claimed that they experienced discrimination when seeking health care, compared to 10% of White respondents. A significant portion of minorities believe that access to COVID-19 testing and treatment could be negatively impacted by their family’s access to healthcare. One respondent explained, “My family lives in an area that has a large concentration of Black people, and we already experience a lack of health care facilities. Many people have tested positive for COVID-19, but there aren’t any testing centers nearby so I’m sure many more people have it unknowingly. There are not enough testing kits in the general area, and hospitals are nearing capacity.” Minority communities, which already saw concerning health disparities before the onset of the pandemic, are much more likely to see a higher and deadlier infection rate than the general population, especially without the proper resources to identify new COVID-19 cases as they emerge. Even with insurance, some families are unsure if they can receive timely and affordable testing or treatment. One multiracial respondent stated, “We don’t have the greatest insurance, so I worry that our network won’t have the resources to help us or that they won’t be covered completely by our insurance.”

While there is ample evidence demonstrating racial disparities in COVID-19 infections and deaths, some maintain the idea that the virus treats everyone equally. In late March, American singer Madonna popularized the phrase “the great equalizer,” characterizing COVID-19 as a virus that, “doesn’t care how rich you are, how famous you are, how smart you are, where you live, how old you are…it’s made us all equal in many ways” (Owoseje). Though a well-meaning message, factors like living and working conditions, which are directly tied to education level and socio-economic status, create an objectively unequal platform for Black and Hispanic individuals in the United States.

Others view unequal infection rates as a product of self-destructive behavior rather than a systemic issue. In April, Surgeon General Jerome Adams, “warned Black Americans to stop drinking, smoking, or doing drugs for their ‘big momma’ and ‘pop-pop’ as the community has suffered a disproportionately high number of virus-related deaths” (Barone). As the highest-ranking public health official in the country, more than 300 million people rely on Adams to spread accurate medical information concerning the pandemic. Blaming high rates of COVID-19 in minority communities on individual action when systemic racism runs rampant through the very same healthcare system designed to help them is a fatal misjudgment that has cost countless Black and Brown lives during this pandemic.

To address these health disparities, the United States government must take a more involved role in including minorities in this discussion. Addressing systemic racism will require this country to reform systems flagrant with inequity such as education, employment, housing and healthcare—in the immediate context of the pandemic, this means heavily considering input concerning socioeconomic, cultural, educational, and linguistic barriers faced by minorities as we develop federal preparedness and response plans (Hutchins et al. 68).

The main misstep of the government is failing to coordinate a coherent response with feedback from minority communities on a federal, state, and local level, particularly as most state and local authorities make their own decisions regarding pandemic protocols. As we move forward, we must continue collectively gathering, analyzing, and applying information concerning racial and ethnic disparities in order to protect the livelihood of Black and Hispanic populations for the remainder of the pandemic and beyond.

David Bradford’s professional interests include neuroscience, sociology/public health, and pre-medicine.