More than Just a Virus: COVID-19 as a Progenitor of Hate

Claire Huang

#iamnotavirus

The outbreak of COVID-19 in the U.S. coincided with a recent wave of nationalism, a criminally incompetent federal government, and a staggering economic decline —creating a set of conditions from which anti-Asian sentiment has sprung vigorously back to life. As of April 2020, Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, a nonprofit based in Los Angeles, received over 1,100 reports of ‘anti-Asian hate incidents’ within the first two weeks of setting up a hotline (Campbell and Ellerbeck). 32% of Americans have seen Asians attacked due to Covid-19, according to an Ipsos survey conducted by the Center for Public Integrity.

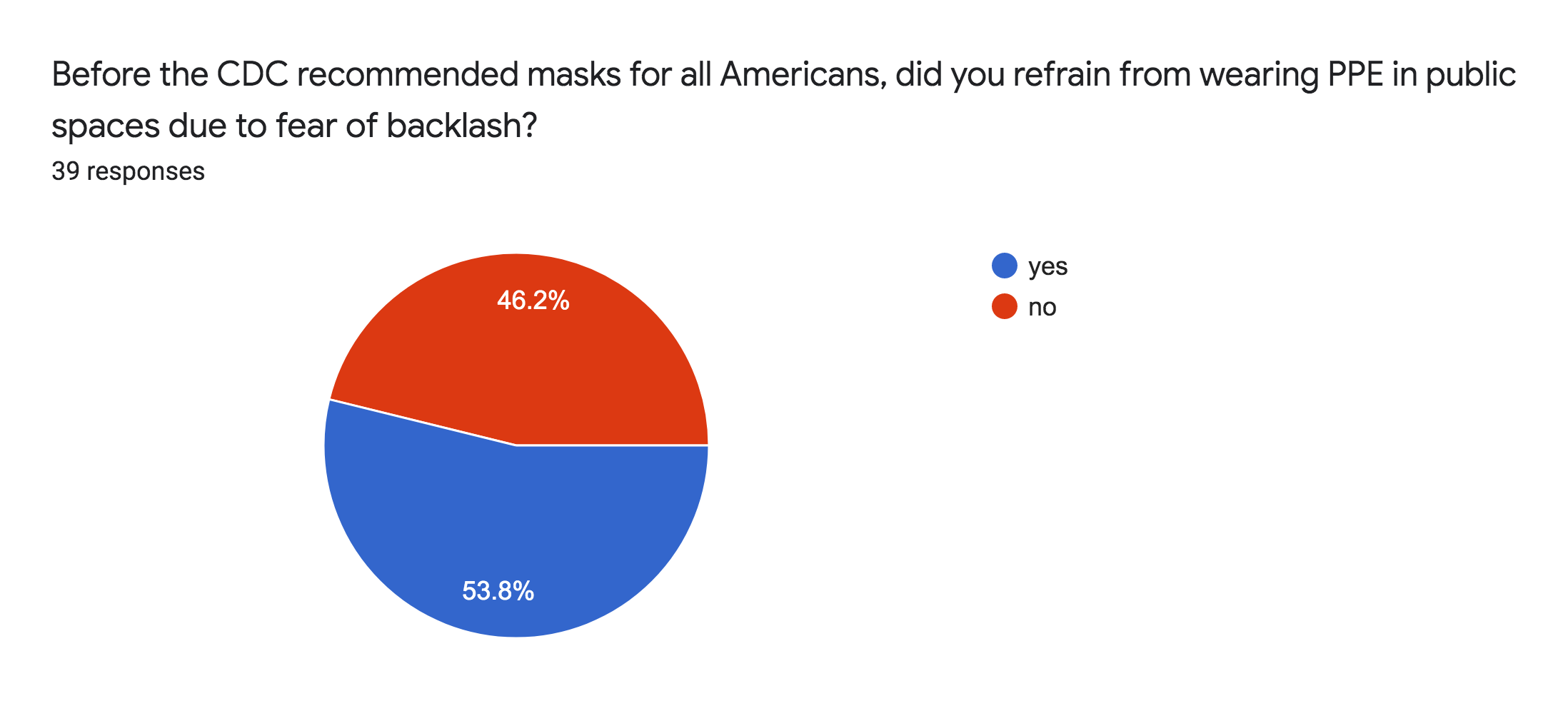

All this fear, of course, has led to significant impacts on the Asian American psyche. In the absence of a comprehensive nationwide survey of Asian American sentiments regarding the recent spike in hate crimes, I decided to conduct my own survey of Asian American students at Washington University in St. Louis. I asked if they refrained from wearing PPE in public due to fear of backlash (prior to the CDC recommending masks for all Americans).

There were 39 respondents, many of whom are part of Chinese Students’ Association and other Asian student groups as recognized by the Asian Multicultural Council at WashU. More than half said yes.

This statistic is particularly telling in that it demonstrates that the majority of students in this sample are more fearful of suffering discriminatory attacks than they are of actually contracting COVID-19.. This clearly indicates how anti-Asian sentiment has become perhaps even more widespread than the disease itself. Asian Americans are having a difficult time dissociating themselves from the disease, and, as a result, have been taking steps to disassociate themselves from the American imaginations of the characteristics that make up the Asian identity (mask-wearing being one of them).

In addition to the startling psychological effects that COVID-19 has visited upon Asian Americans, they are also suffering from an economic crisis far worse than the average newly-unemployed American. The vast majority of Asian-owned businesses in the U.S. were already reporting significant decreases in sales in the months preceding the outbreak in the states. After the outbreak, the unemployment rate for Asian Americans grew by 1.6 percent, compared to only 0.9 percent for white workers. As a result of COVID-19, much of the economic progress made by low income and middle-class Asian Americans in the past few decades will have ground to a halt.

This is all to say that special efforts need to be made by the federal government to ensure that Asian Americans are able to economically recover from the COVID-19 crisis in a timely manner, on par with other racial and ethnic groups.

For what it’s worth, the Asian community has largely banded together during this time. Social media outlets have been set up to map out incidents across the U.S., and initiatives like @sendchinatownlove have been started to support and reinvigorate Asian-owned businesses that are close to shuttering. Politicians such as Grace Meng (D-NY) have introduced resolutions calling on Congressional leaders to denounce anti-Asian sentiment caused by COVID-19 and some scientific organizations have expressed disapproval of using rhetoric that ascribes diseases to ethnicities.

These efforts are admirable, but nothing that has been done thus far has significantly reduced the ferocity of the ever-growing tide of anti-Asian sentiment in America. In fact, the federal government’s sense of responsibility towards Asians seems to have actually degenerated over time: During the SARS epidemic, the CDC became so concerned about anti-Asian hostility that they “launched a 14-member community outreach team in the same week the agency reported the first 5 confirmed cases of SARS in the U.S.” (Campbell and Ellerbeck). This outreach team was immediately sent out to speak to Asian community leaders, conduct panel discussions aimed at easing tensions, and analyze phone data from thousands of calls to the CDC hotline to determine best responses.

By comparison, the CDC refused to comment when a letter signed by the likes of Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris questioned why the CDC has not yet set up similar initiatives to address the backlash against Asians due to Covid-19. President Trump has issued just one flimsy statement, in the form of a Tweet, that encouraged the ‘protection’ of Asian Americans who are ‘amazing people’. This, just after he glibly referred to COVID-19 as the ‘Chinese virus’ and had no problem with senior White House staff referring to it as the ‘kung flu’.

Protection of Asian Americans should consist of unequivocally and publicly denouncing anti-Asian sentiment, assembling a task force to talk to community leaders to gain insight into the specific struggles Asians are facing, prioritizing small business loans for Asian Americans and Chinatowns, and setting up committees to keep track of Asian Americans’ mental and physical health throughout and after the crisis.

Public relations campaigns should be instituted to help combat the spread of xenophobia through media engagement. The World Health Organization had no problem contracting popular Youtube, Tik Tok, and other social media creators to make videos about hand-washing, so why not do the same for #IAmNotAVirus?

Corporate America also needs to be held accountable. For every firm with Asian employees, a commission should be set up to keep track of what proportion of Asian employees are being let go as compared to the proportion of white employees who are being laid off.

Unlike its microscopic counterpart, the virulence of xenophobia cannot be solved with a simple vaccine. It takes the right people to make the right decisions, and sooner rather than later.

Claire Huang’s professional interests include management consulting, investment banking, government/public policy, and foreign service.