Facemasks, Bathbombs, and Essential Oils

Oct 2022

The Commodification of Self-Care

Shawn Zhu

What comes to mind when you think of self-care? Perhaps a candle-lit spa session complete with cucumber-eye-masks? Or maybe a home cooked meal made from organic, free-range chicken with a kale smoothie on the side? How about going on an early morning hike? But why is it that these are the images that arise when we think of self-care? After all, the definition of self-care is frustratingly ambiguous — “the practice of taking action to preserve or improve one’s own health,” according to Oxford Dictionaries. Indeed, the “self-care” industry has exploded to more be worth more than $10 billion, complete with facemasks, bath bombs, and even “candles that smell like Gwyneth Paltrow’s vagina.” I argue that the self-care industry is the result of neoliberalism’s tendency to treat health as an issue contained within the individual, where commodities and activities that fit within the neoliberal ideal of personal productivity are glamorized. Furthermore, the proliferation of “self-care” products has been aided by its trending status on social media. Social media has twisted our perceptions of self-care and wellness, providing curated portrayals that have contributed to the commodification of wellbeing.

In today’s society, the concepts of health and wellness have been constructed to fit the neoliberal expectation of being productive in the market. In “Neoliberalism and the Commodification of Mental Health,” authors Luigi Esposito and Fernando M. Perez argue that mental health concepts are social constructs, and that the classification of mental disorders are driven by both politics and profits. In the context of America’s neoliberal market society, where “success, virtue, and happiness…are often associated with material wealth, prestige, and coming out on top,” wellness or normalcy means achieving these objectives (Esposito and Perez). The neoliberal framework also minimizes the effects of the environment, and instead assumes that individuals are entirely responsible for their own actions. For example, under the neoliberal framework, “homelessness among those with severe mental illness is viewed as stemming primarily from their illness rather than the lack of inexpensive housing” (Cohen). Furthermore, the authors argue that “acquiring services and/or products that might aid people to meet these results is thus viewed as benevolent and perhaps even indispensable in the pursuit of a fulfilling and productive life.”

The assertions the authors make in their article fits within a larger body of work known as critical psychiatry. Proponents of critical psychiatry point out problems in the diagnosis of mental illnesses, arguing that the criteria for certain illnesses are left dangerously vague, and are highly subjective due to the lack of biological bases (Thomas and Bracken). The vagueness of diagnosis opens up the possibility for individuals to self-diagnose, and look for ways to medicalize their supposed illness. They criticize the increasing medicalization of psychiatry, driven by the corporatization of the medical world, which can be seen in the ever-expanding categories of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM): the first edition of the DSM had 106 categories of psychiatric disorders, while the fourth edition had 354 (Thomas and Bracken). As a result, “these presumed illnesses and their treatments are turned into commodities, or brands, that can be bought and sold” (Esposito and Perez). The transformation in the diagnosis of childhood depression serves as a perfect illustrator for how mental health is medicalized for corporate gain. Prior to the 1980s, childhood depression was considered a rare diagnosis, and was understood to be incurable through medical means (Timimi). The third edition of the DSM, published in 1980, drastically changed this understanding by including a diagnostic criteria for childhood depression; the new DSM also asserted that childhood depression could be treated by medication (Timimi). The result was a surge in diagnosis for childhood depression, despite the fact that the criteria for diagnosis is so broad that it may as well be useless (Timimi). By the end of 2003, “over 50,000 children were prescribed antidepressants, and over 170,000 prescriptions a year for antidepressants were issued to people under 18 years old in the United Kingdom” (Timimi). It should be no coincidence that this transformation occurred alongside an increasing commercialization of childhood; an industry of consumer goods for children, from TV shows to toys, was being developed (Timimi).

The self-care industry, therefore, is an extension of the medicalization of mental health, where commodities like skincare products, juice cleanses, and various other pampering products are advertised as effective “treatments” for deteriorating mental health. Instead of addressing institutional issues at the root of individual burnout and stress, like the lack of social support in the workplace and unrealistic working hours, self-care is but another way the neoliberal framework diverts systemic failures onto the individual. Much like drugs prescribed for supposed mental illnesses, self-care treatments are advertised as ways to “modify behaviors to fit normative patterns of neoliberal agency,” such as suppressing feelings of depression and anxiety in order to better one’s productivity in schools/workplaces.

But self-care wasn’t always a huge commodity industry selling pampering products and self-help books. In the 1960s to 1970s, self-care emerged within academic settings as a way for professionals whose work focuses on death and bereavement to cope with work-related stress and prevent burnout. The International Federation of Social Workers emphasized the importance of self-care in its “Statement of Ethical Principles and Professional Integrity,” stating, “Social workers have a duty to take the necessary steps to care for themselves professionally and personally in the workplace, in their private lives and in society” (Powers and Engstrom). This statement is most commonly encapsulated in a phrase far too common to social workers, “You can’t give from an empty well” (Powers and Engstrom). Once again, the same neoliberal framework that assumes health and wellness as the responsibility of the individual is imposed upon social workers, despite social work being a profession that consistently experiences the highest rates of stress, burnout, and job turnovers (Powers and Engstrom). However, while self-care was originally a practice siloed within the profession of social work, it gained universal influence following the 2016 presidential elections: the week after the election, Americans googled the term “self-care” almost twice as much as they had in years past (Harris). Following a particularly tumultuous and emotionally damaging election, self-care became the new chicken soup for progressives and activists coping with burnout.

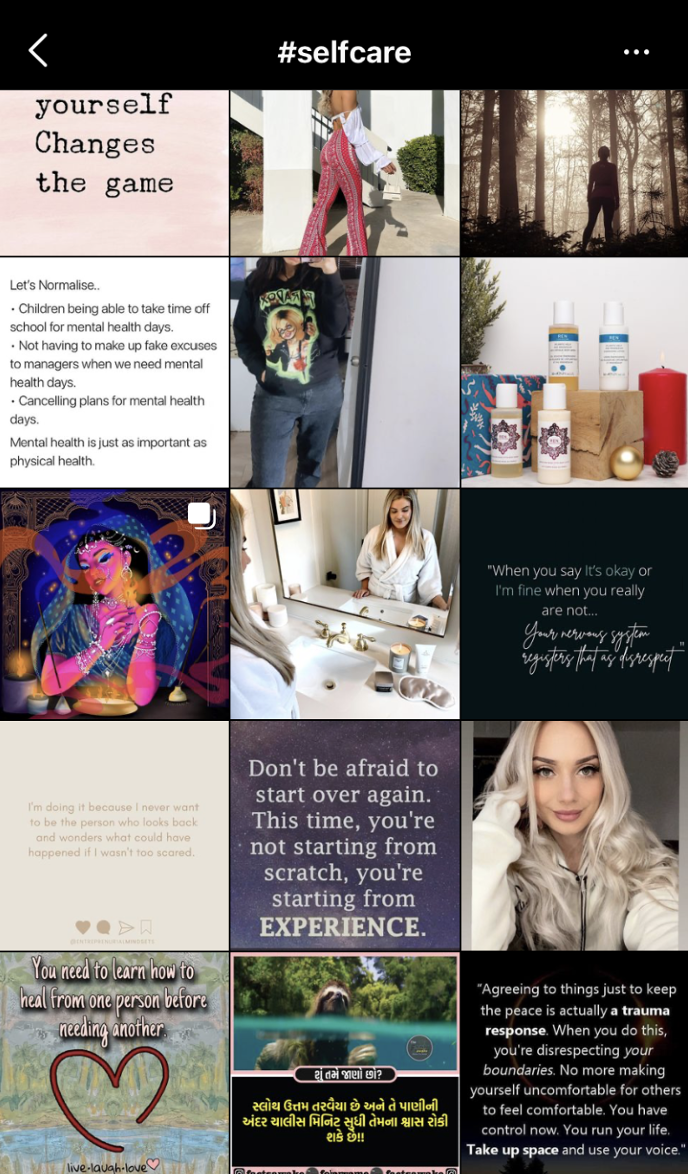

A large part of the self-care boom should be attributed to the role of social media: influencers posing with candles and bubble baths, bloggers raving about the latest self-help books, and tiktokers posting their laborious self-care routines. Today, browsing under the “self-care” hashtag yields 56.5 million posts on Instagram, and videos under #SelfCare have garnered a combined 15.1 billion views on the popular, video-focused social networking app called TikTok.

Immediately apparent while exploring the ocean of #SelfCare posts are the prevalence of product advertisement. Amongst the plentiful inspirational quotes set against a black background are influencers posing in mirrors alongside products from their latest sponsors. Zooming in, elaborate displays of a shampoo and body wash kit are photographed with the hashtag of self-care in its caption. In this manner, one’s health and wellness are conflated with the ability to purchase an endless stream of products, a blatant signal of the commodification of wellness by social media. The popularity of self-care trends has propelled businesses to use it as a marketing technique: luxury products like toiletries, skin-care, and clothing are reframed as more than just luxuries, but a way for individuals to improve their wellness.

However, the new trend of self-care doesn’t just stop at specific products, but extends to one’s overall lifestyle. In a 43-second TikTok, content creator Emily Mariko (@emilymariko) takes us through the process of making an arugula, beets, and almond salad without speaking a word. The video is taken in her expansive and pristine kitchen, complete with enough dishware to host a party of 20 (Mariko). Everything in the video, including the video itself, is well organized: the almonds sit neatly in a mason jar; the veggies are bagged in their own respective Ziploc bags; and the table marble countertop is absolutely spot-free. Throughout the video, Emily keeps a contented smile on, a face absent of any worries. Here, Emily presents one form of “self-care”: finding therapy in making wholesome food for oneself. Though there may be nothing wrong with the content of Emily’s video (her account has in fact quickly blown up and has acquired over 7 million followers in under a year), the comments under the video reveals how influencers commodify self-care, and how it can twist the audience’s perceptions of wellness.

“I can’t wait to have my own place so I could cook like this. It seems so therapeutic,” says user @giovanacarillo0. Their comment signifies how the supposedly universal experience of cooking food has been commodified by the luxuries presented in glamorous kitchens. The innately therapeutic nature of making healthy food becomes associated with the upscale kitchenware rather than the action of cooking itself. Other comments reveal how the commodification of “self-care” has made it inaccessible to many, captured by comments left by the likes of @xxo..miabella..xxo: “Ain’t nobody got the time for that.” Most interesting, however, is a comment left by @katharron17, which garnered over 86 thousand likes: “I like to imagine this is how I’d live if I wasn’t depressed.” The comment accurately displays how portrayals of “self-care” can twist the audience’s perception of wellness: the audience conflates “wellness,” a highly subjective term, with the lifestyle Emily Mariko has chosen to portray in just 43 seconds. The lifestyle portrayed in Emily’s video — an organized, healthy, and worry-free life — becomes a new goal that the audience seeks to acquire. Notice once again how the neoliberal framework of mental health is in effect: Emily’s “lifestyle” is perceived as healthy and normal because it fits within the neoliberal framework of normalcy: being productive, even when she’s performing “self-care.” The implied understanding, hence, is that those who aren’t organized, seem worried, and eat “unhealthily” display symptoms of depression (not surprisingly, these tendencies just so happen to fit within the DSM-5’s diagnostic criteria of depression).

Emily’s videos represent a popular content format: short, well edited vlogs that show-case creators performing various forms of self-care, including skincare, cooking, and vacations. Much like Emily’s videos, they’ve had a similar effect on changing people’s perception of wellness and self-care. I interviewed several undergraduate students at Washington University in St. Louis on their experiences with self-care, in both their personal lives and through social media. When asked about their personal definitions of self-care, their answers somewhat varied across the board. “The purpose of self-care is to reflect on one’s needs, to better yourself in the aspects that you think you need to be bettered,” one said (Kim). “Self-care to me is taking a day off from work and doing things that I find relaxing,” said another (Kirti). When asked “what are the first things that come to mind when you think about self-care,” however, their answers had shocking overlaps. Out of the five students I interviewed, four of them mentioned some form of skin care when answering the second question; three of the students mentioned either “taking a bath” or “bath bombs” in their answer. The similarities in their answers, despite differentiated definitions of self-care, shows how self-care has been commodified. Social media trends have twisted people’s perception of what self-care is.

I then asked my interviewees about whether or not they followed self-care accounts similar to Emily Mariko’s on Instagram or TikTok. If they answered yes, I followed up with another question, “How does watching these self-care videos make you feel?” One girl responded, “They make me feel like…I need to do more? I think inadequate is a good word for it. Like they [the content creators] are doing so much and I’m doing so little” (Kane). Another echoed her sentiment, “They make me feel…unproductive. It always seems like they have their lives so put together” (Kim). The feelings of inadequacy and unproductiveness that self-care videos can elicit is the exact critique Charlotte Lieberman gives in her article “How Self-Care Became So Much Work.” Lieberman points to a cultural symptom of America’s neoliberal framework: “Americans glamorize work and busyness, so it’s no surprise that their approach to ‘self-care’ involves goals and counting steps. In a way, our high anxiety becomes just another thing to ‘work on.’” She further asserts that under the culture of productivity, it’s easy for self-care to turn into self-criticism, especially when prompted by social media (Lieberman). Truth is, the commodification of self-care has made it entirely inaccessible to most, and has transformed it into yet another fashionable trend that only the wealthy can participate in.

Given all the critiques of self-care, what is to be done? Certainly, self-care has had some beneficial impacts on society. For one, its immense popularity has raised awareness for mental health; there is unquestionable value in learning to care for oneself and learning mechanisms to destress. Secondly, not all self-care commodities are inaccessible luxuries that offer little benefit. Mindfulness practices, defined as “a process of openly attending, with awareness, to one’s present moment experience,” is one form of self-care that has garnered varied support from experts (Creswell). Popular mindfulness interventions include mindfulness-based stress reductions (MBSRs), usually implemented over an eight-week period within a clinical setting. These interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing stress, and thereby alleviating physical pain as well as reliance on pain medication (Creswell). The interventions have also shown effectiveness in reducing anxious thoughts and feelings, as well as preventing depression relapses (Creswell). On top of that, a wave of smartphone apps has hit the App Store that offers mobile mindfulness meditations at an accessible price (Creswell).

Ultimately, self-care isn’t an egalitarian practice, although the industry tries to present itself to be; there’s no one blueprint that’s proven to better one’s wellness. Social media has twisted our perceptions of wellness and fed us specific methods of achieving “wellness,” which usually fit in line with neoliberal norms of productivity. The self-care industry has also benefited from the medicalization of mental health. The ever-increasing diagnosis for mental illnesses has made it possible for just about anyone to be diagnosed with depression or anxiety, and self-care products have become a new treatment for individuals. Hence, in moments of stress, it may be helpful to step away from social media, and refer back to a personal definition of self-care: doing whatever makes you feel the most relaxed.

Works Cited

Creswell, David J. “Mindfulness Interventions.” Annual Review of Psychology, Jan. 2017, annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139.

Esposito, Luigi, and Fernando M. Perez. “Neoliberalism and the Commodification of Mental Health.” Humanity & Society, vol. 38, no. 4, Nov. 2014, pp. 414–442, doi:10.1177/0160597614544958.

Harris, Aisha. “How ‘Self-Care’ Went from Radical to Frou-Frou to Radical Once Again.” Slate Magazine, 2017, slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2017/04/ the_history_of_self_care.html.

Kane, Michelle. Personal Interview. 4 December 2021.

Kim, Rachel. Personal Interview. 4 December 2021.

Kirti, Pranav. Personal Interview. 2 December 2021.

Lieberman, Charlotte. “How Self-Care Became so Much Work.” Harvard Business Review, 10 Aug. 2018, hbr.org/2018/08/how-self-care-became-so-much-work.

Mariko, Emily. [@emilymariko]. (2021, October 4). [Video]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@emilymariko/video/7015323069199715590

Powers, Meredith C.F., and Sandra Engstrom. “Radical Self-Care for Social Workers in the Global Climate Crisis.” Social Work, vol. 65, no. 1, 11 Dec. 2019, pp. 29–37, doi.org/10.1093/sw/swz043.

Thomas, Philip, and Patrick Bracken. “Critical Psychiatry in Practice.” Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, vol. 10, no. 5, 2004, pp. 361–370, doi:10.1192/apt.10.5.361.

Timimi, Sami. “Rethinking childhood depression.” BMJ, vol. 329, no. 7479, 2004, pp. 1394–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7479.1394.

Tsai, Audrey. Personal Interview. 1 December 2021.

Xian, Stephanie. Personal Interview. 1 December 2021.

Shawn Zhu is from Shanghai, China and studies in the College of Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.