BI-N-G-O!

Oct 2022

The Role of In-Group Stereotypes in Bisexual Communities

Alice Hu

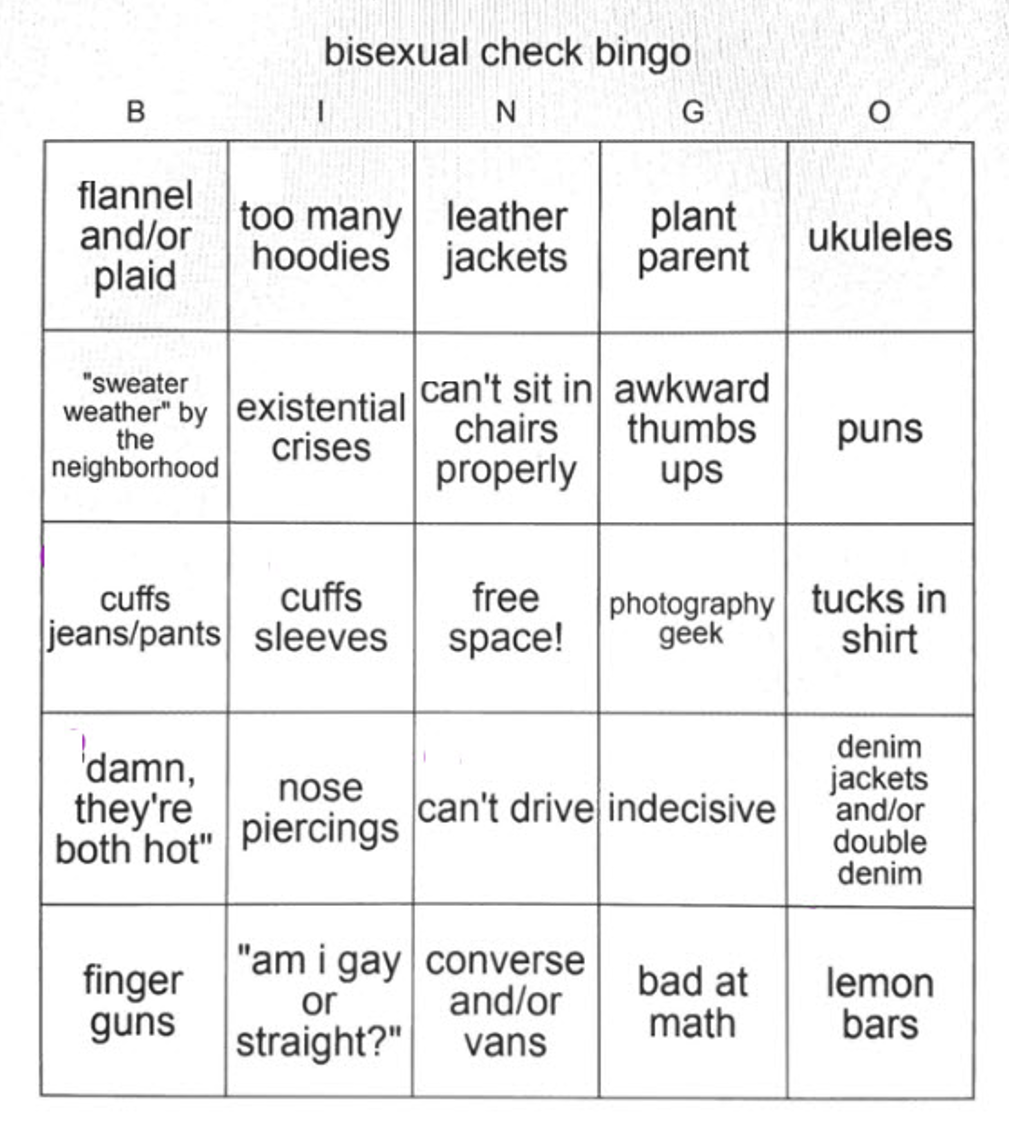

Blank Bisexual Bingo Card,

from u/dan_woodlawn in r/bisexual

Midway through my first semester in college, I went to the barber and had most of my hair chopped off my head. When asked about my motivations for such a drastic change, I would smile and give a canned response about wanting to try something different in college or remark idly about donating hair for the first time. That was all true, of course. But what I left unsaid was possibly an even stronger motivation: a hope that when people saw me across campus, a flicker of recognition would cross their faces, and they would notice that I was not straight. Why was that? It wasn’t as if the short crop of my hair or the cuff of the sleeves on my button-down shirts were what made me a part of the LGBTQ+ community, and in fact, that sort of blatant stereotyping — that gay people have to “look” a certain way — has more negative connotations for social progress than positive. Yet here I was.

My impression that cuffing my sleeves might allow other people to recognize me as bisexual didn’t come from nowhere; it was in large part informed by what I’d observed in bi people assigning themselves stereotypes online in games like the unofficially named Bisexual Check Bingo, with cards such as the one here. This card comes from r/bisexual, an online community on Reddit, a website where people can discuss and make posts about various topics. As such, it was circulated mainly among bisexual people (or those of adjacent identities), with an objective of marking squares that one found relatable and sharing the results with others in the subreddit. The purpose of the game is in good fun; no one is going to be ousted from the community for not getting “bingo.” This sentiment is even reflected in the post’s top comment: “Bisexual culture is having most of these and still not getting bingo” (u/dan_woodlawn). Curiously though, despite the collective understanding that this is all just a silly diversion, the existence of the bingo card itself implies, in however tongue-in-cheek a manner, that there exists a correlation between the items in the bingo chart and being seen as bisexual (consider: “Bisexual culture is having most of these”). Thus, while it is a misguided idea to treat this online bingo card as definitive proof of anything, it may be worth examining what its details imply for the dynamics of bisexual community as a whole.

A cursory glance at the board reveals a focus on outward appearance, with nine squares out of twenty-five (36%) describing some element of clothing or fashion and an additional three squares (12%) focusing on aspects of physicality like “can’t sit in chairs properly” or “awkward thumbs ups.” By contrast, there are only two squares relating directly to bisexuality as an orientation: “’damn, they’re both hot’” (referring to both members of a heterosexual couple) and “’am i gay or straight?’ [sic]” (u/dan_woodlawn). In his PhD dissertation, LGBTQ+ studies professor and researcher Justin J. Rudnick discusses the topic of LGBTQ+ identity understood through visual signifiers and performed cues rather than its direct disclosure, exploring personal accounts from himself and other individuals in the LGBTQ+ community to argue for a consideration of both “coming out” and “being out” as expressions of queer identity. He highlights the “body’s centrality in communicating queer identity” where the “body” refers to visual signifiers such as “emphatic gestures, jewelry, gender inversion, clothing and accessories…[etc.]” (112). In Rudnick’s words, these signifiers “articulate embodied approaches to represent an identity commonly thought to have no definitive physical identifiers” (112).

The “embodied approaches” that Rudnick describes draw parallels to the various squares on the bingo chart, which includes “emphatic gestures” like finger guns, clothing like leather jackets, and accessories like nose piercings. As well, he presents an interesting potential reason for their importance: the lack of “definitive physical identifiers” (Rudnick 113) of queer identity. In other words, sexual orientation does not manifest in obvious physical characteristics in the same way as identities such as race or sex, so it is in some sense invisible without the presence of these secondary signifiers. This invisibility is likely the force behind the concept of being “in the closet,” where in a heteronormative society everyone is assumed to be heterosexual until they disclose themselves as otherwise (Rudnick 113). Because of this assumption of heterosexuality, the performance of one’s queer identity — whether through a direct “coming out” statement or through more subtle, hinting behaviors — becomes tantamount to living authentically in a way where one’s identity can be recognized by others.

Notably, bisexuality is invisible even by LGBTQ+ standards, as even the presence of a same-sex or opposite-sex partner (the one form of non-verbal disclosure that generally distinguishes straight folk from gay folk), cannot be relied on to express a person’s bisexuality. By that account, surely it must be even more important for bi community members to emphasize their shared stereotypes of affect and fashion. Despite this, the visual stereotype of a bi person reads as much more esoteric than that of a gay man or lesbian. Returning to the bingo card as an example, many of these squares refer to items that the average non-bisexual layperson would likely not associate with bisexuality at all, like ukuleles and peculiar sitting habits. In contrast, visual stereotypes for gay men and lesbians, as well as for LGBTQ+ folk as a collective, are more well-defined, calling to mind images of men with makeup and crop tops, women with flannels and beanies, or anyone with brightly dyed hair and cat-eye glasses. What does the stereotypical bisexual look like, to someone who hasn’t been exposed to the concepts of cuffed jeans and Converse as indicators?

All this is to say that in order to perform a bi stereotype that can be used as a signifier to others in the community, the users of r/bisexual have had to construct their own stereotype of what a bisexual person looks like and does. Many of the visual signifiers discussed come from observations of shared fashions, established as a “bisexual thing” over time through continued acknowledgement — in other words, enough bi people were cuffing their sleeves that someone eventually took notice. However, the bingo board is not exclusively outward fashions, and thus neither is the content of the bisexual stereotype being constructed. Certain entries, such as with the squares for “indecisive” and “‘am i gay or straight?’ [sic],” bear a superficial resemblance to negative stereotypes held about bisexuals from outside of the bi community, specifically those of bisexuals being confused or just going through a phase (u/dan_woodlawn). Because they are shared within a bisexual space, the phrases are stripped of their predominantly negative connotations (e.g., “indecisive” comes to mean indecision with regards to general choices rather than indecision with regards to sexuality or romantic partners). This reflects a sort of digital version of what scholar Kee-Yoon Nahm describes regarding stereotypes in theatrical performance, remarking that performances of negative stereotypes can have their effects “tempered by the power of the body” (Nahm 94). Nahm here refers to the body of an actor, but the same general concept can be applied to any person performing their own identity in a shared space. In the same way that a Black performer putting on blackface would have a different effect to a white performer putting on blackface (Nahm 94), the statement that “bisexual people are indecisive” has a much different connotation coming from a community of bisexuals than if it were coming from a group of non-bisexuals. To that end, by subverting these negative stereotypes in their creative re-stereotyping of themselves, the people engaging with this bingo card can, in effect, escape the negative identity brought on by out-group stereotypes against them. Even more so, the ease with which the people within the community can joke about these subjects speaks to a level of comfort with stereotyping that is specific to in-group communication and bonding. The bisexual bingo card revolves around a stereotype of bi people that only exists among the bisexual in-group, and not as a parodiable character for the predominantly heterosexual world at large. Consequently, the people playing bingo are engaging in self-stereotyping in a way not meant to be perceived by the out-group. The power of these in-group stereotypes is such that even harmful stereotypes can become a shared experience for the group to laugh about, forging closer bonds within the bi community.

That said, the bisexual archetype presented by the bingo board is by no means ubiquitous. Some of the bingo squares correspond directly to in-jokes specific to certain online communities — “lemon bars,” in particular, is a reference to a single post made by a Reddit user linking bisexuality and lemon bars essentially at random (“R/bisexual - Anyone else wonder”). It pays to remember that this bingo chart was circulated first and foremost among a subreddit, meaning the stereotypes it references characterize a specific online circle more accurately than it does the overall bisexual population. In an analysis of the LGBTQ+ cyberspace of “Gay Twitter,” Nino Giuliano Zulier describes the circulation of “fringe vocabulary,” a manner of vernacular used by the gay in-group to connect with each other and serve as a “symbolic protection against hetero-invasion” (103).

The text of the bingo card may not be as slang heavy as a space like Gay Twitter, but the same principle applies; certain concepts are circulated among a more niche community as a form of code to differentiate between the in-group of people who “know” and the out-group of people who don’t. However, the overlap between the people who understand the fringe vocabulary and bisexual people is not absolute, and there are plenty of bi individuals who have not encountered these specific references, as evidenced by a comment by a user on the bingo post commenting, “As a bi man in his 30s I’m so invisible I’m not even on this card” (u/dan_woodlawn). This can have a two-fold effect of increasing camaraderie among the group that identifies with the archetype and alienating the group that does not. As helpful as these in-group archetypes can be for forming community, the approach is not without its downsides.

Nevertheless, I would argue that this alienation is inevitable, especially when considering the challenges inherent to connecting a bisexual community. No social group is a monolith, of course, but bi people have often occupied a space between gay and straight experiences that has not been well defined. Some bisexual people are open about their orientation and take issue with the assumption that they have a preference for one gender over the other; others are in committed relationships with a person of one gender and as such their bisexuality may never be acted upon; still others accept their attractions to multiple genders but eschew labels in favor of a more fluid approach. This is further complicated by the fluidity of sexuality and of individuals’ understanding of their own orientation over time; for example, a woman who has dated men for much of her life before realizing her attraction to women will likely have a different set of experiences to a woman who previously identified as lesbian and now considers herself to be bisexual. Add to this the experiences of bisexual people of other genders, and the range only gets further expanded. Thus, it can be difficult to find similarities that will resonate with most or all bisexual people. To illustrate, sociologist Kristin G. Esterberg, in Lesbian and Bisexual Identities: Constructing Communities, Constructing Selves, delves into personal experiences of lesbian and bisexual women, highlighting a story about the “Bi-Weekly Bi’s,” a college support group for bisexual women that was a great source of community for the women involved until the graduation and interpersonal conflicts of some individuals caused the group to fall by the wayside (158–159). It can be inferred from the way the group came to an end through the actions of individuals that the Bi-Weekly Bi’s, despite the name, was more likely bonded as a small friend group than on account of their bisexuality. Therefore, orientation alone is not likely to be the strongest motivator for keeping a community together. Perhaps more telling is the fact that aside from the Bi-Weekly Bi’s, the women interviewed by Esterberg did not have any larger bisexual communities to reference, with one woman lamenting that “[t]here are simply too few open bisexuals to make a real community” (Esterberg 160). This recalls the idea of bisexual invisibility as mentioned earlier, which arguably necessitated the creation of the group archetype in the first place. Thus, the approach laid out by Bisexual Check Bingo, of characterizing the typical bisexual person as a cuffed, awkward ukulele player with a closet full of jackets and a penchant for frenetic hand gestures, is despite its blind spots an honest attempt at finding commonalities to bond over within the group.

It is perhaps for this reason that I felt compelled to cut my hair in the way that I did. While on the surface it may seem a shallow attempt to fit in with a gay stereotype, this interpretation disregards the importance of visibility to a queer person trying to establish their identity. To someone who is already comfortable with being “out,” being publicly recognized as such can reaffirm the reality of their identity and lead to them forming connections with others who share that identity. As silly as the bisexual bingo card is, it speaks to a real approach that the online bisexual community has taken to finding each other by recognizing the common threads in the way that they perform their bisexuality and sharing the observations of these common threads with each other. It serves as a way for bisexual people to see each other across the room in a sea of heteronormativity. Because of the theoretical invisibility of bisexual identity, bi communities are to some degree reliant on stereotypical affect. What can be discovered, then, is the use of specifically in-group stereotypes as a tool — not as a tool to divide, as out-group stereotypes often are, but as a tool to unite a community with a kaleidoscope of unique experiences.

Works Cited

“R/bisexual – Anyone else wonder what’s up with the lemon bars? Here’s the answer-from the source (with links!).” Reddit, Reddit Inc. 13 Jun. 2018, reddit.com/r/bisexual/comments/8qsmyl/anyone_else_wonder_whats_up_with_the_lemon_bars.

Esterberg, Kristin G. Lesbian and Bisexual Identities: Constructing Communities, Constructing Selves. Temple University Press, 1997.

Nahm, Kee-Yoon. “Subvert/Reinscribe.” Performance Research, vol. 21, no. 3, 2016, pp. 92–102.

Rudnick, Justin J. Performing, Sensing, Being: Queer Identity in Everyday Life, 2016. Ohio University, PhD dissertation. ProQuest Dissertation and Theses Global. wash-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/q1cvd5/TN_cdi_proquest_journals_1850524282.

u/dan_woodlawn. “R/bisexual – Blank Bisexual Bingo Card.” Reddit,30 Sept. 2019, reddit.com/r/bisexual/comments/dbaf3n/blank_bisexual_bingo_card.

Zulier, Nino Giuliano. “Conceptualization of a Queer Cyberspace: ‘Gay Twitter.’” Freiburger Zeitschrift für GeschlecterStudien, vol. 27, no. 1, Jan. 2021, pp. 95-111, doi.org/10.3224/fzg.v27i1.07.

Alice Hu is from Wilmette, IL and studies in the College of Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.