Discriminatory Presentation of Asian Art in U.S. Art Museums

Oct 2022

Cindy Bu

Fig 1

Saint Louis Art Museum. Above: “Real and Imagined Landscapes in Chinese Art” (March 11–August14, 2016). Below: “The Monochrome Mode in East Asian Art” (August 21, 2020–February 14, 2021).

Visiting a public art museum of the United States, people usually encounter what is called the “encyclopedic museum” or “universal survey museum,” which is a museum that “collects, displays, and teaches art without geographical or material limits” (Ward 2). Along with other cultures being displayed in these art museums, with decades of effort, Asian arts became a standard part of the collection of the US art museums in the later 20th Century (Lee 359). However, while we deem these art museums as universal and objective, presenting a global perspective that informs the public about different cultures, it is unfortunately not usually the case. How curators should exhibit the non-Western culture has continued to be an issue, including in the Asian arts. Admittedly, there is an increasing effort addressing the recognition and proper presentation of Asian arts in the art museum, such as special exhibitions and increasing recruiting of Asian art. For example, the Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM) installed a special exhibition, “Real and Imagined Landscapes in Chinese Art,” from March 11 to August 14, 2016, and “The Monochrome Mode in East Asian Art” from August 21, 2020, to February 14, 2021 (Figure 1). SLAM also appointed Philip Hu, who has curated many exhibitions and rotations for the art museum, as the curator of Asian art since 2016. Despite all these gratifying efforts, there are still many problems that remain in the representation of Asian art, and increasing recognition of these issues is still needed.

This research paper will primarily use the SLAM as a case study to address the Asian art display issue in the context of United States art museums. I will also address the Metropolitan Museum of Art (metmuseum.org) as comparison to SLAM for it serves as a renowned art museum providing museum models for art museums in the US. Admittedly, art museums like SLAM face understandable limitations, both spatial and financial and are already putting effort into displaying Asian art. Yet it is still worth thinking about better ways to arrange these artworks and how to tell these artists’ stories better. There are three primary issues presented in Asian art today — arbitrarily determined geographical display, choice of only antique Asian art objects, and misrepresentation of Asian artists’ intention. I propose potential solutions to this problem that, if considered, can foster a greater appreciation for and understanding of Asian art and may also help in eliminating stereotypes and discrimination in culture, given that art museums play a prominent role in public education.

Visitors might not realize how they are directed in a certain way to navigate the galleries in the art museums. People typically encounter the European master’s artworks first and then the Asian ones juxtaposed with them. Donald Preziosi, the Emeritus Professor of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles, asserts that by arranging objects in specific ways, museums are “disciplining modern populations to construe history as the unproblematized or even natural evolution or progression of styles, tastes, and attitudes from which one might imaginatively choose as one’s own” (165–166). The dictatorial path determined by the curator, which has long persisted since the emergence of Asian arts in U.S. art museums, has taught the audience to habitually receive information in art museums and never question its problematic nature.

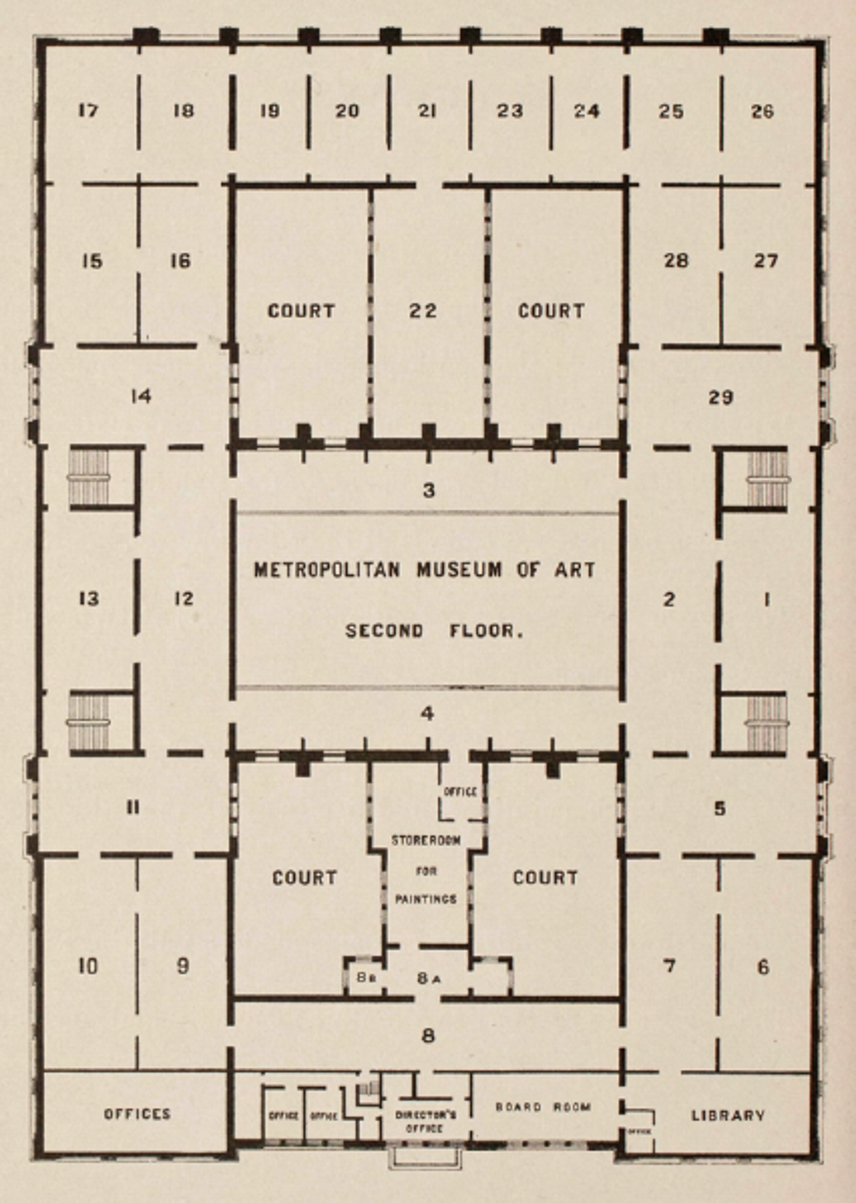

Fig 2

Map of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Second Floor from Ward, Logan. “Museum Orientalism: East versus West in US American Museum Administration and Space, 1870-1910”; originally from, Guide to the Halls and Galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1894). Related gallery labels: 1. Gallery of Paintings by Old Masters; 2. Gallery of Paintings; 3. Gallery of Chinese Porcelain; 4. Gallery of Drawings by Old Masters, Etching, and Photographs; 12. Gallery of Modern Paintings; 13. Gallery of Modern Paintings.

The late 19th century was a time of proliferation of art museums founded in great cities across the eastern half of the United States, with the MET assuring its supremacy position as the museum model in America (Hoffman 124). Joining this trend late in this decade and following MET’s model, SLAM was then founded. Given MET’s influential position on US art museums, including SLAM, it is also worth examining the inclusion of Asian art in the MET before going directly to the analyzing SLAM. In 1895 when Chinese ceramics were first prompted to be included in the MET, they were situated in a hallway connecting the two main European paintings galleries (Figure 2). People must visit the European masters' paintings as they enter the second floor and “wound a path through either temporary exhibitions or musical instruments and Euro-American antiquities” (Ward 12–13). The designed floor plan of the art museums arbitrarily assigned the visitors to a single path, forcing them to compare the grand European masters’ work with the Asian arts and educating the audience in a universal way. Having the European masterworks in mind first creates a Western version of the standard of beauty in the visitor’s mind, thus alienating arts of other cultures as a deviation from that standard and, therefore, inferior. As a result, people are imbued with the idea that Asian arts serve an auxiliary position to the Western arts—their beauty seems only to stand up as an opposition to the Western style, and their existence seems only to be dependent on the Western masterworks.

The positioning of Asian arts seems to be better but actually still needs more effort to treat them properly. In today’s SLAM, Asian artworks are placed in an L-shape corridor on the right side of Level 2. There are two routes to get to visit the Asian art gallery. One way is to enter the European galleries full of the European masters’ paintings first; the other is by directly entering a long corridor that exhibits the bronze and jade crafts from prehistoric China and its earlier dynasties. On the surface, it is encouraging to see that SLAM tries to counter a universal way of navigating the museum, which is what the MET did in 1895 for the Asian gallery. However, a deeper analysis reveals an implicit tendency of preference for the visitor to choose the first way described: encounter the European Master’s paintings first and then the Asian artifacts.

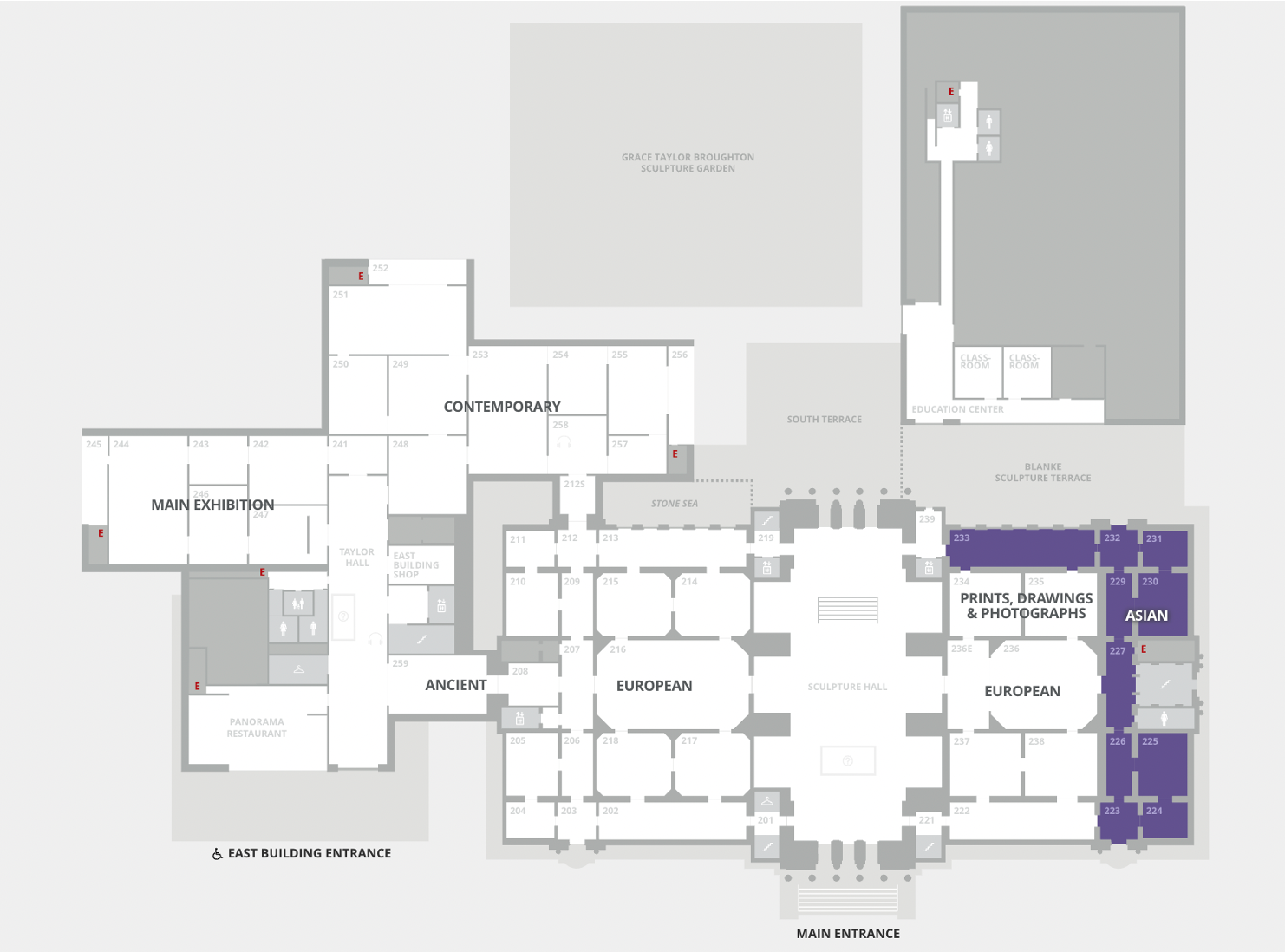

Fig 3

Saint Louis Art Museum Floor Plan: Level 2.

Fig 4

Saint Louis Art Museum: European Gallery. (Photo by Cindy Bu)

Fig 5

Saint Louis Art Museum: Sculpture Hall from the view of the main entrance: the entrance to the Asian Art Museum is represented by the red circle. (Photo by Cindy Bu)

As people step into the main entrance and pass the information desk, the open, grand, bright gateway on both sides of the visitors (Gallery 216 and 236E) lures the visitors into visit these galleries first (Figure 3–4). The order is presumed by the architectural design. In contrast, the Asian galleries are to be entered at the end from Gallery 233, near the exit to South Terrace (Figure 3, 5). If not walking the whole distance, one might not realize an opening to these galleries in the sculpture hall. Thus, the so-called “diverse” way of navigating the art is still arbitrary, mimicking the history of MET’s floor plan in 1895. Similar to the MET, the Asian artworks are still a viewed as a supplement to the Western masters' painting. They are still used for contrasting, juxtaposing, and emphasizing the difference between East and West in the art museum, a representative of the deviation from the Western standard.

The possible solution to this issue would be to reorganize the artworks as though they could be approached differently and let the visitors choose their path themselves. For example, for SLAM, the art museum might not have European paintings occupying both left and right galleries near the main entrance. The essential point is to allow none of these non-Western cultures to serve as if their interpretation must rely on the Western artworks, but rather allow a separate and independent understanding of the audience on these artworks.

Aside from the geographic location of the artworks in the art museums, another strategic move being used to emphasize the contrast between East and West is the inclusion of specific works for Asian cultures, the antique crafts, and the exclusion of others, the modern arts. Such a move in conjunction with the geographical juxtaposition of the Western and Asian galleries further emphasize the binary stance of East and West. As Sonya S. Lee, associate professor of Chinese art and visual cultures at the University of Southern California, states, the Asia galleries’ choice of objects on display often underscores “antiquity, tradition, and refinement,” and “placement within the museum building suggests a degree of intraregional unity that stands in contrast to the tastes and values of Western society” (359). Unfortunately, SLAM utterly resonates with what Lee depicts.

Navigating the Asian galleries of SLAM, one might think they are stepping back to those glorious dynasties, viewing all these elegant vases, jars, boxes, etc., from ancient craftsman’s hands. The static ancient Asian artifacts stay in stark contrast to the progressive, changing styles and materials of European paintings on the same floor level — not to mention the avant-garde artworks from modern European and American artists on the other floor levels. The awe and appreciation of Americans for Asian arts remains in the ancient eras and the “dynasties” of these Asian countries, ignoring those modern developments of Asian artists both within and outside the states. This one-sided presentation of Asian artworks thus creates an emblematic image of Asia that fits the Western idea of “otherness,” a contrast to their artwork. It reduces Asian art into a single character type in which “Asia” equals “ancient.”

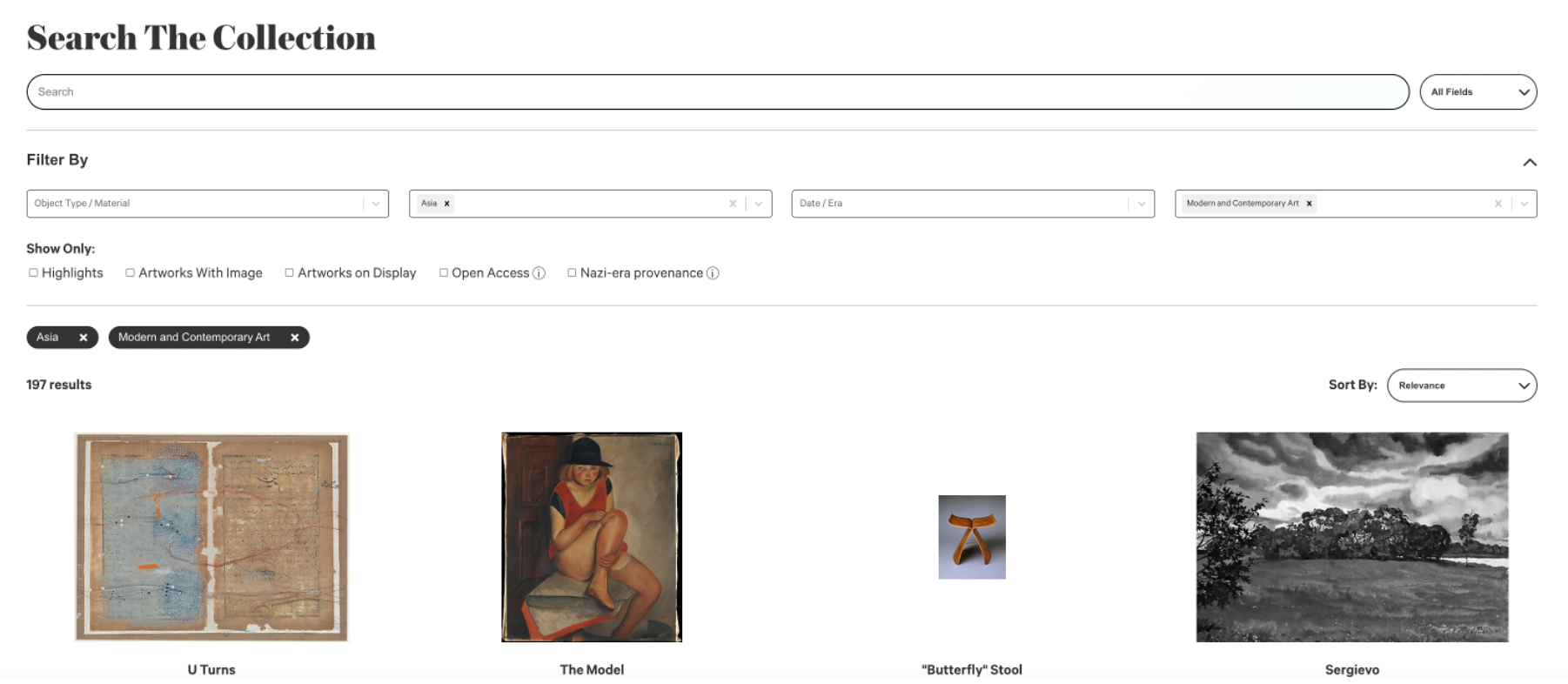

Fig 6

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met Collection. Search the Collection with filter “Asia” and “Modern and Contemporary Art” – 197 results.

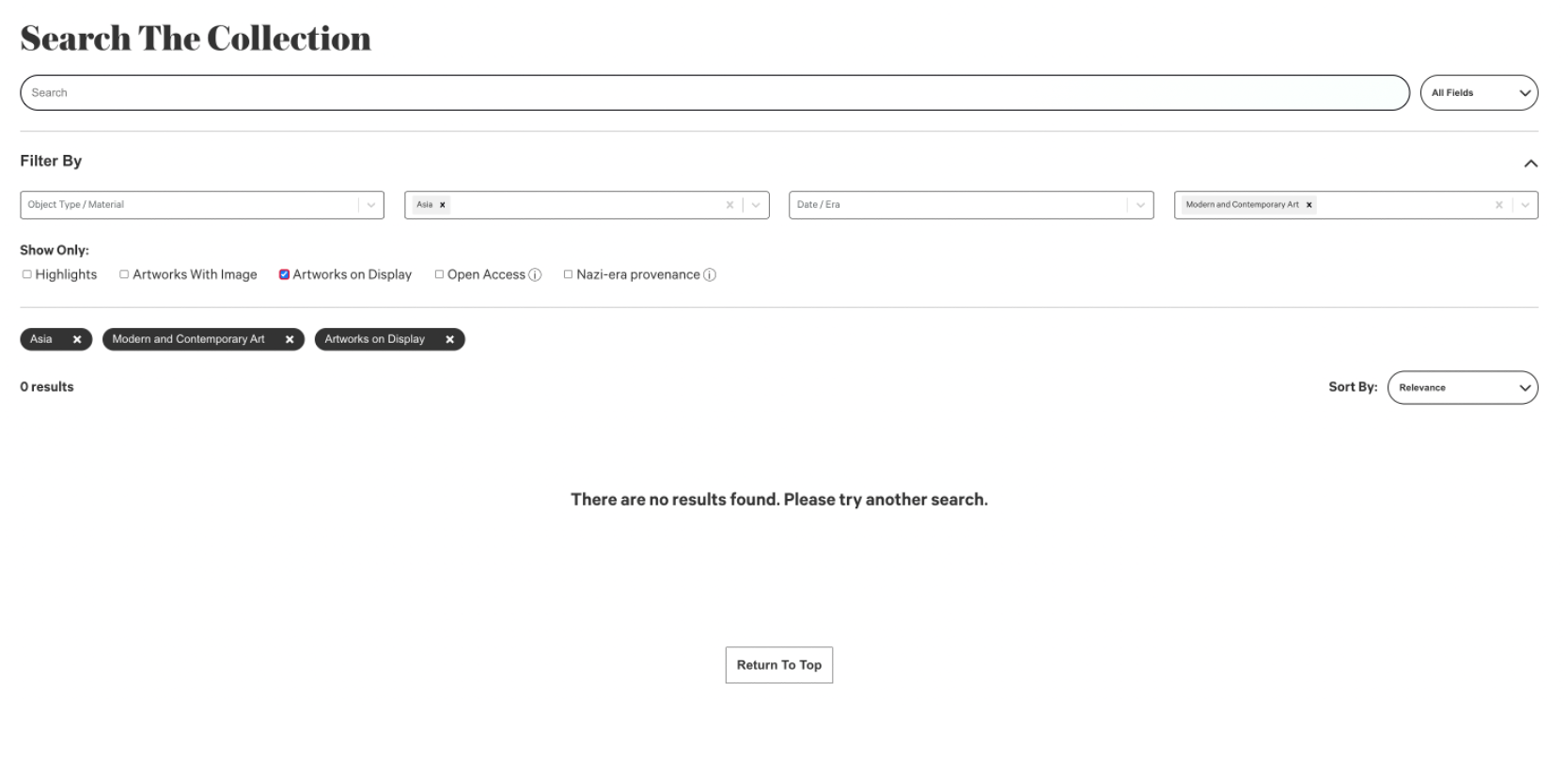

Fig 7

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met Collection. Search the Collection with filter “Asia” and “Modern and Contemporary Art” and “ARTWORKS ON DISPLAY” – “There are no results found. Please try another search.”

Fig 8

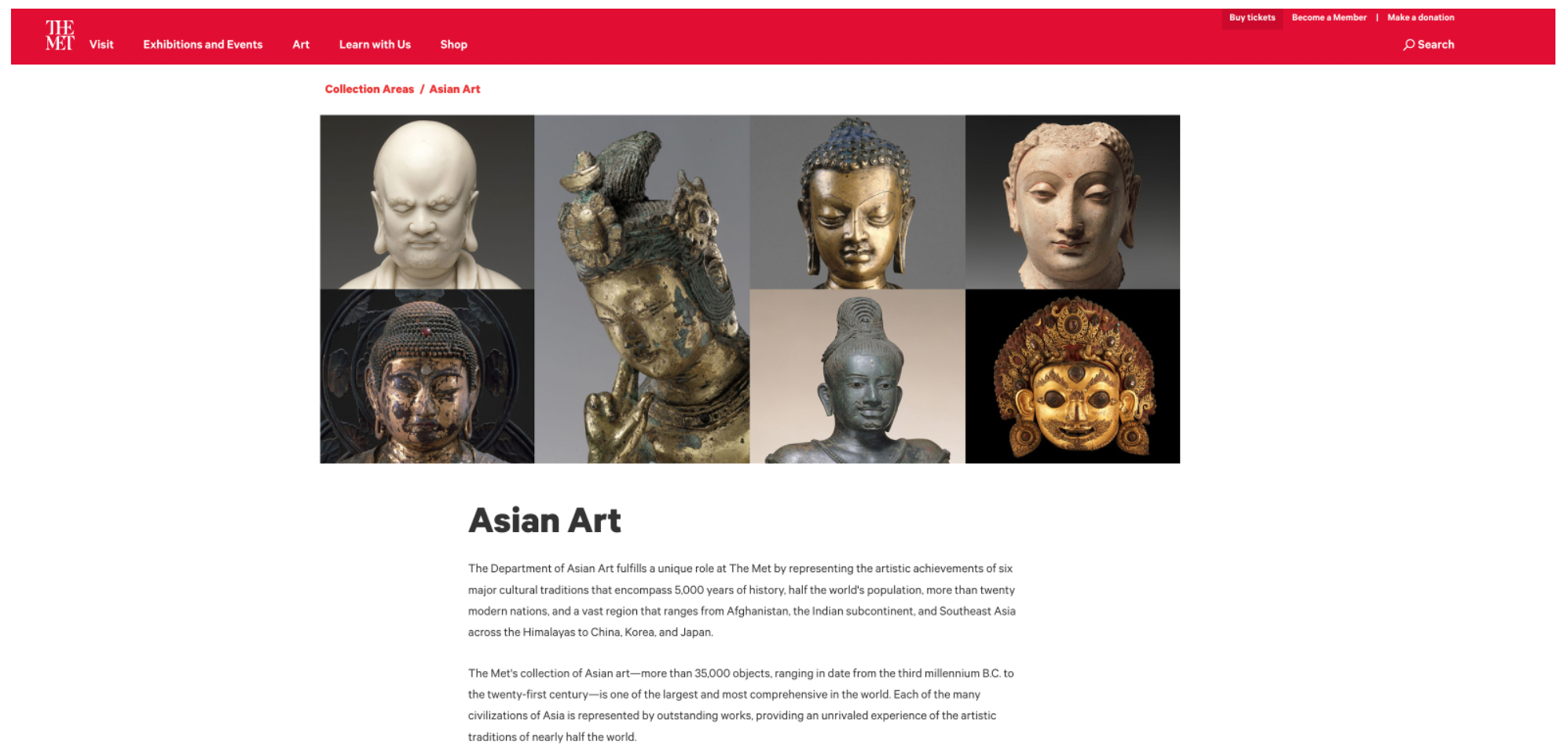

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Asian Art.”

One might argue that SLAM, as a local art museum, might not gain enough artworks for them to tell the whole story of Asian cultures. But even for art museums like the MET, the largest art museum in the Western Hemisphere, having 2000 Asian objects, there are still underlying issues regarding recognizing modern Asian artworks. On the official website of the MET, there are 197 Asian artworks under the Modern and Contemporary Art category (Figure 6). Sadly, none of the artworks show up when clicking on the “Artworks on display” but a message telling the visitors to “try another research” (Figure 7). For the official page designed for “Asian art,” the MET proudly indicates their span of Asian art dated from “the third millennium B.C. to the 21st Century” (“Asian Art”). However, ironically, the cover photo on that page includes universally only ancient sculptures, most of them of Buddha, and none of the modern artworks they have (Figure 8). Even when the art museums have the contemporary Asian arts in their collection, none of them is determined by the curator that they are worth a space at the regular exhibition of the art museum and are essentially excluded from receiving recognition from the visitors.

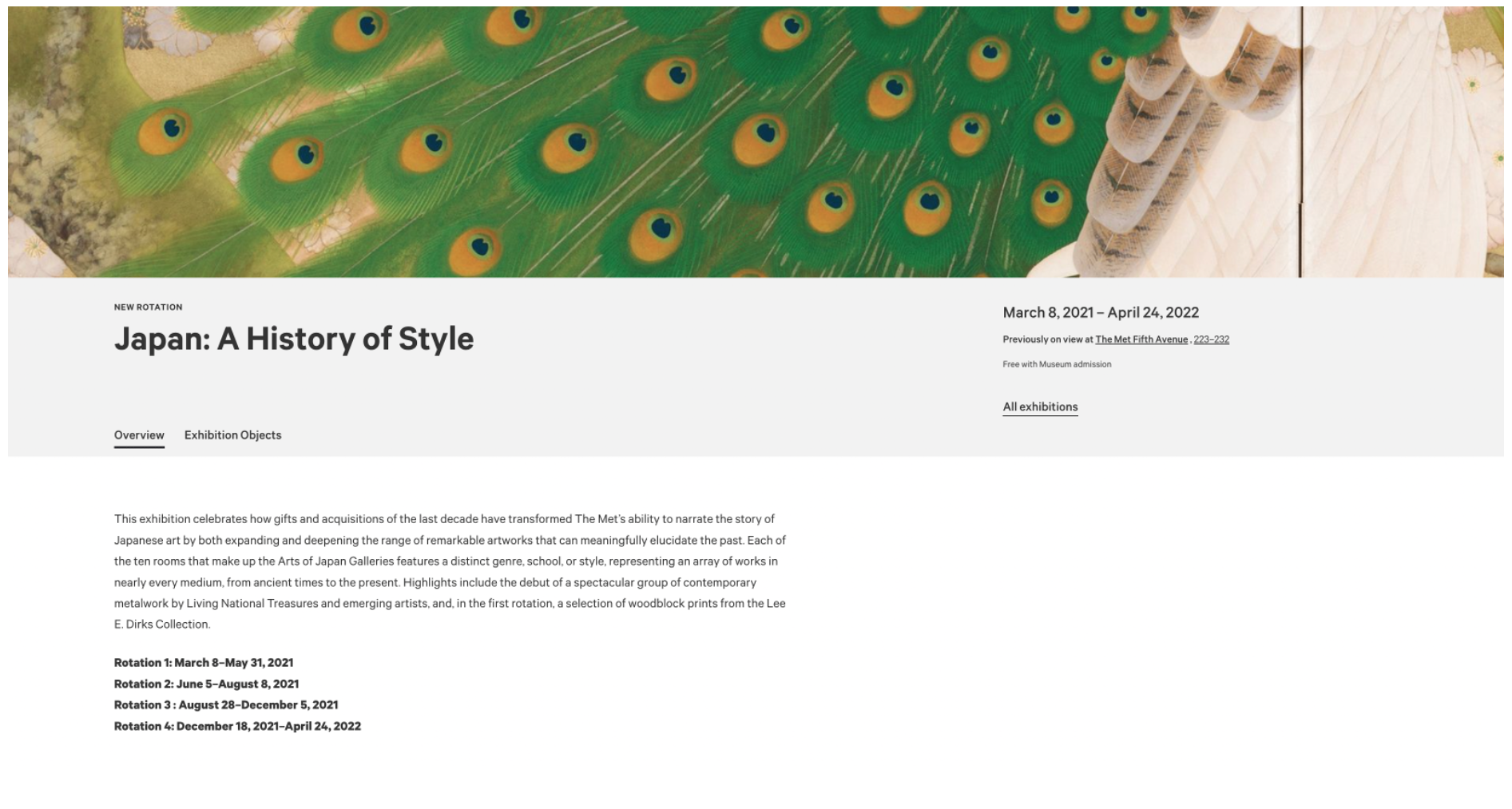

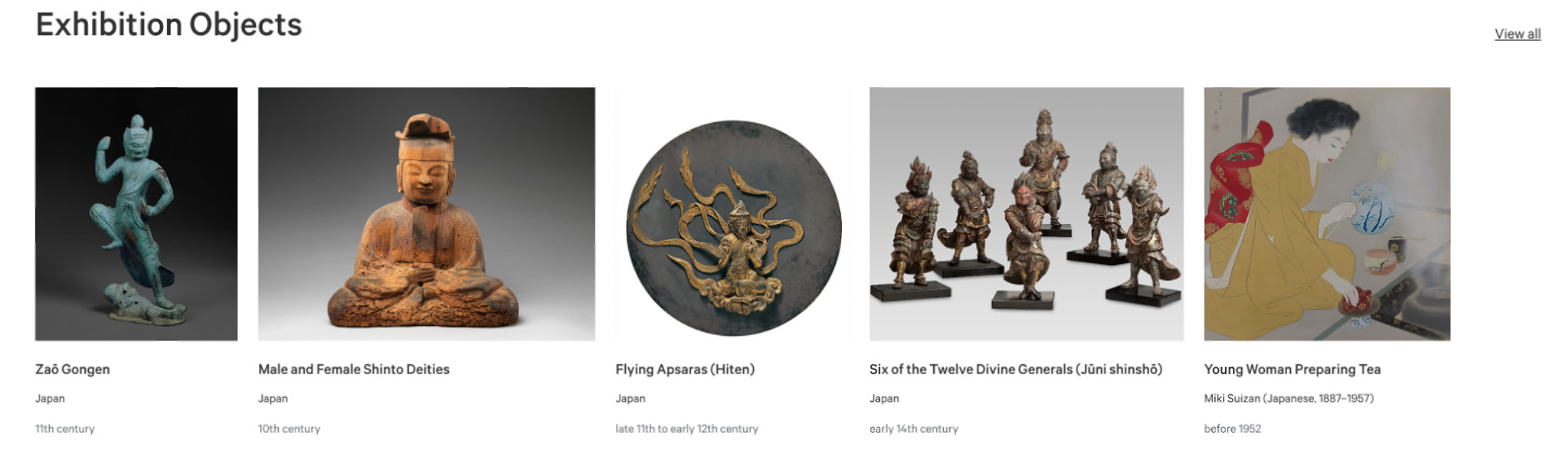

While there are no Asian modern artworks on display, there is one praiseworthy special exhibition that the MET has organized, “Japan: A History of Style” (Figure 9). The special exhibition consists of ten rooms, each with a distinct genre, school, or style in a wide variety of mediums, representing artworks from ancient times to the modern period (8th century to 21st century today) [1] . This kind of exhibition is a good and proper way to improve the incomprehensive and arbitrary view of Asian Arts. This special exhibition at the MET expresses Japanese culture as an independent entity that develops and flourishes on its own. By displaying diverse and non-homogenous Asian art, the art museum, especially those with these extensive collections of Asian artworks like the MET, shows that they have the potency to narrate the whole story of Japan better as they have claimed. These art museums have the ability to present a better picture of the alternative culture if they are willing to see their special exhibition “Japan: A History of Style” as a model. They can feasibly choose several modern artworks they have to be displayed in the regular collections and recognize them on their official website in prominent places (“Japan”). It is just an issue of willingness rather than capability.

Fig 9

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Japan: A History of Style.”

Fig 10

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Japan: A History of Style.” – Exhibition Objects

Fig 11

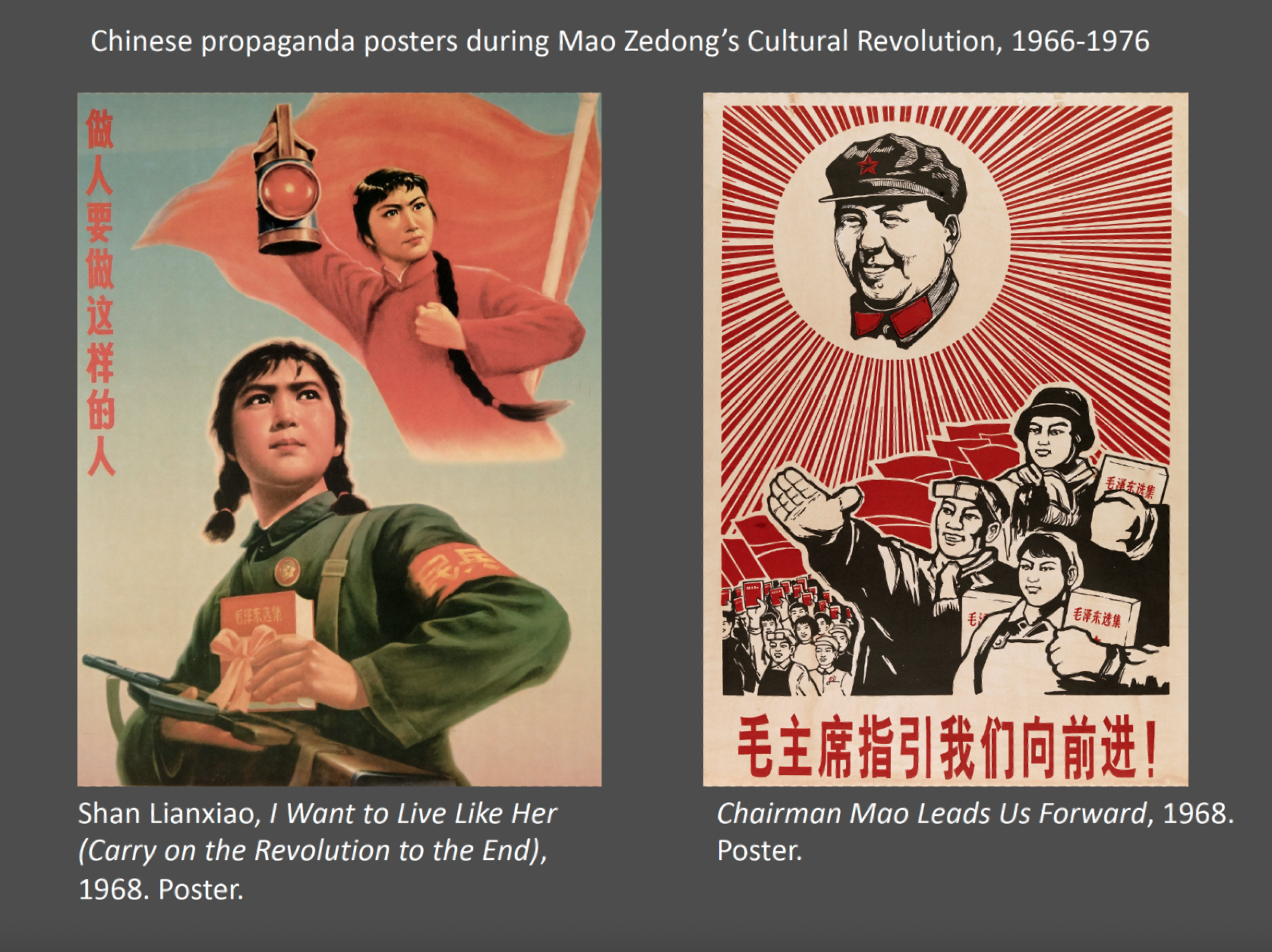

Wang Guangyi’s artist page on the website of Saatchi Gallery

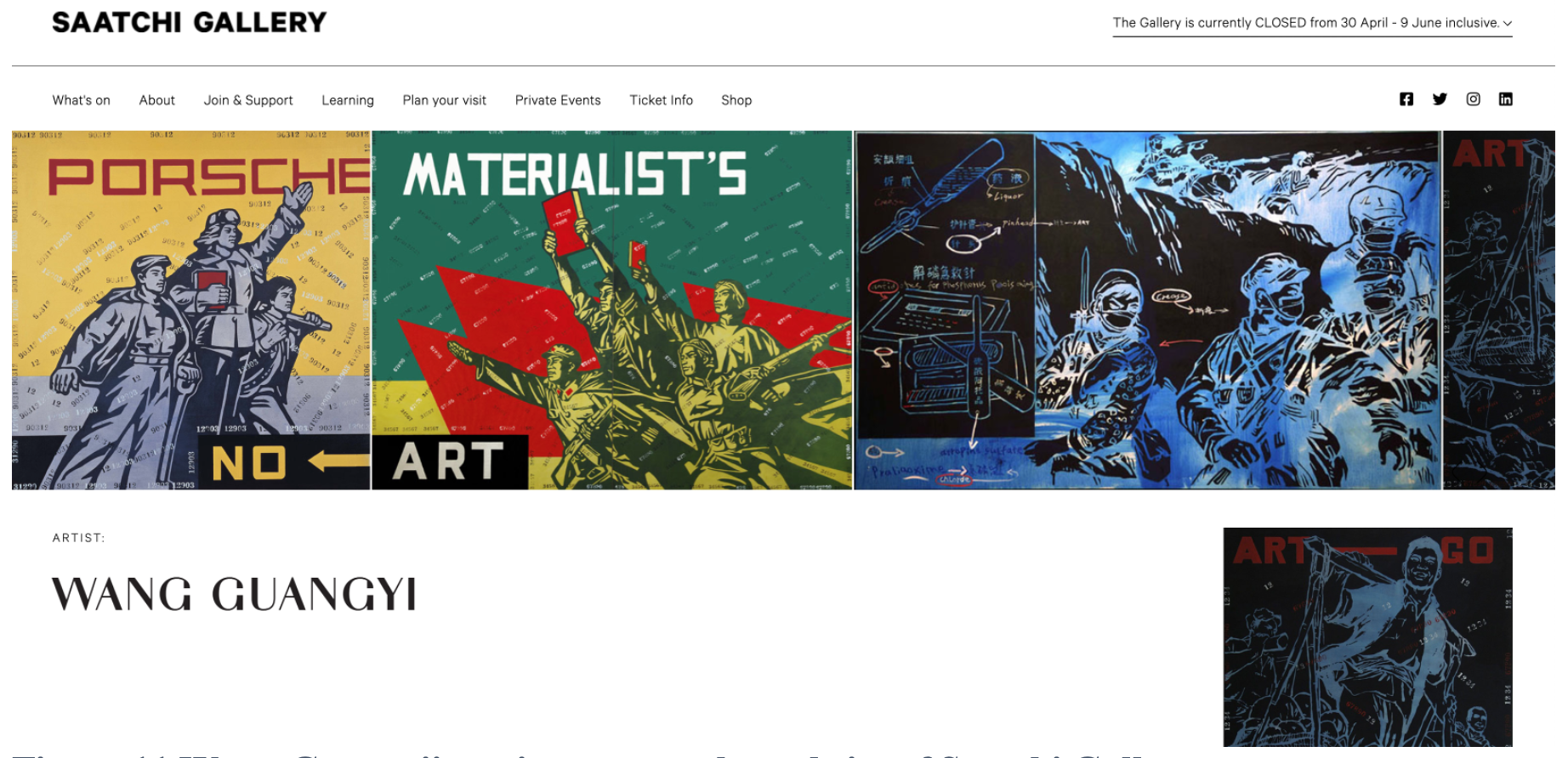

Other art museums that include Asian contemporary art in their exhibition seem to take a further step from SLAM and the MET. Nevertheless, they still reflect a Western-centered view where they often prefer to include Asian artworks that fit Western ideology. For example, US art museums favor Wang Guangyi, who uses striking imagery of American Pop to criticize communism and the propaganda aesthetics of the Cultural Revolution (Figure 11) (Clarke 238). Wang Guangyi’s concept fits the opposition between the praised democracy and the despised communism in the United States. His style also suits what the U.S. deems “modern” since it is related to US pop art. Thus, while these public art museums seem like an objective and apolitical place, it is not so much. The preference for ancient objects might also be because it is easier for the art museums to deal with Asian artworks by artists who have died. Modern artists are more likely to be politically active and can more likely be against the Western-centric ideology of the museum. As Anna Laura Jones, professor of Anthropology at Stanford University, states in her article “Exploding Canons: The Anthropology of Museums,” “it may seem easier to deal with archives and artifacts that ‘don’t talk back’” (215). The art museums thus avoid the burden of getting “permission” from or coordinating with artists to present their artworks in a way the curator desires.

In general, there is a lack of art museum support for Asian artists in the U.S. for their artwork due to the lack of interest in presenting contemporary Asian artworks, and they have to be their own advocates. Most of their works are stored in grass-root organizations, such as Chinatown Art Brigade (CAB), which is a cultural collective of artists, media makers and activists creating art and media to advance social justice, rather than nationally recognized museums. As a result, the smaller space and staff lead to Asian artworks being less well-stored and well-displayed (Alexander). More importantly, they face a much smaller audience. They are almost always those with specialized interests in Asian and non-Western artworks and have devoted their time to learning about them or those Americans of non-White ethnicities. While White American individuals who travel within the United States have limited time to go to one museum in the city they are visiting, they will definitely go to those free “official” ones in the city center rather than distanced ethnical ones. Thus, only through a nationally recognized museum, one that as a public infrastructure serves the purpose of representing the importance of artworks and the individuals behind them, that the elevation and recognition of these minor groups can be recognized. It is through giving their proper display in public recognition that it is plausible for the discrimination of Asians and other minority groups to be improved in the society.

Fig 12

Hung Liu, Residential Alien, 1988. image source: hyperallergic.com/681445/hung-liu-golden-gate-de-young-museum (Photo by Drew Altizer)

Fig 13

Social Realist Paintings of China. Screenshot from Introduction to Modern Art, Architecture, and Design slides for Hung Liu’s Residential Alien.

Furthermore, it is not only in art museums that the exclusion of modern Asian artworks is carried out, which has to do with the curators, but also the art history taught in Western schools. For instance, the popular American College textbook Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, has only chapter on Chinese art named ‘Ming, Ch’ing, and Later Dynasties’ for the sub-heading and puts it before the European Renaissance art and the narrative of Western art’s subsequent development (Clarke 240). The depiction of Asian art in United States art history education connotes that the only worth-mentioning and respectable Chinese artworks are ancient ones before the Western Renaissance art. The later development of Chinese art is thus inferior to Western art. This alienation of modern artworks in the textbook provides young Americans with a homogeneous view of Chinese artworks, increasing their prejudice against Asians. The public’s false view of Asian arts, further enhanced by the art museums, is rooted and embedded deeply in their minds. My personal experience studying modern art history at Washington University in St. Louis takes it a further step. My professor includes multiple contemporary artworks by artists of Asian heritage, such as Chinese-born American immigrant artist Hung Liu’s Resident Alien (Figure 12). However, similar to the art museums that display Asian contemporary artwork, these artworks are still taught within a Western ideology framework. For example, when talking about Hung Liu’s Resident Alien (Figure 12), the professor refers to the artist’s influence on social realist art as a propaganda instrument of the People’s Republic that showed a harmonious and prosperous society counter to the reality (Figure 13). Though this is true, my teaching assistant for the class, who is Chinese, also pointed out in the subsection she leads that these artworks also reflect the working-class people’s life, enticing the public’s compassion. The whole story is not addressed in the art history course.

The probable solution to this issue is to include more of the contemporary Asian artworks in joint display with the ancient ones, as well as a larger amount of and a more accurate exposure of these Asian artworks in Western art history education. Due to the limitation of space and the amount of artwork each art museum obtains, it might be hard for them to display an equal number of arts to the ancient ones, and it is also not essential to do so. What I want to argue here is to have at least some representation of modern artists’ works on display regularly so that their voices are at least addressed in these public institutions. By doing so, the art museums can tell a more holistic story of Asian art culture and present a more heterogeneous nature of Asian artworks. Adding on to that, the more accurate inclusion of Asian modern arts in art education in the U.S. is also vital as compensation to the art museums for the awareness of contemporary artists’ efforts today.

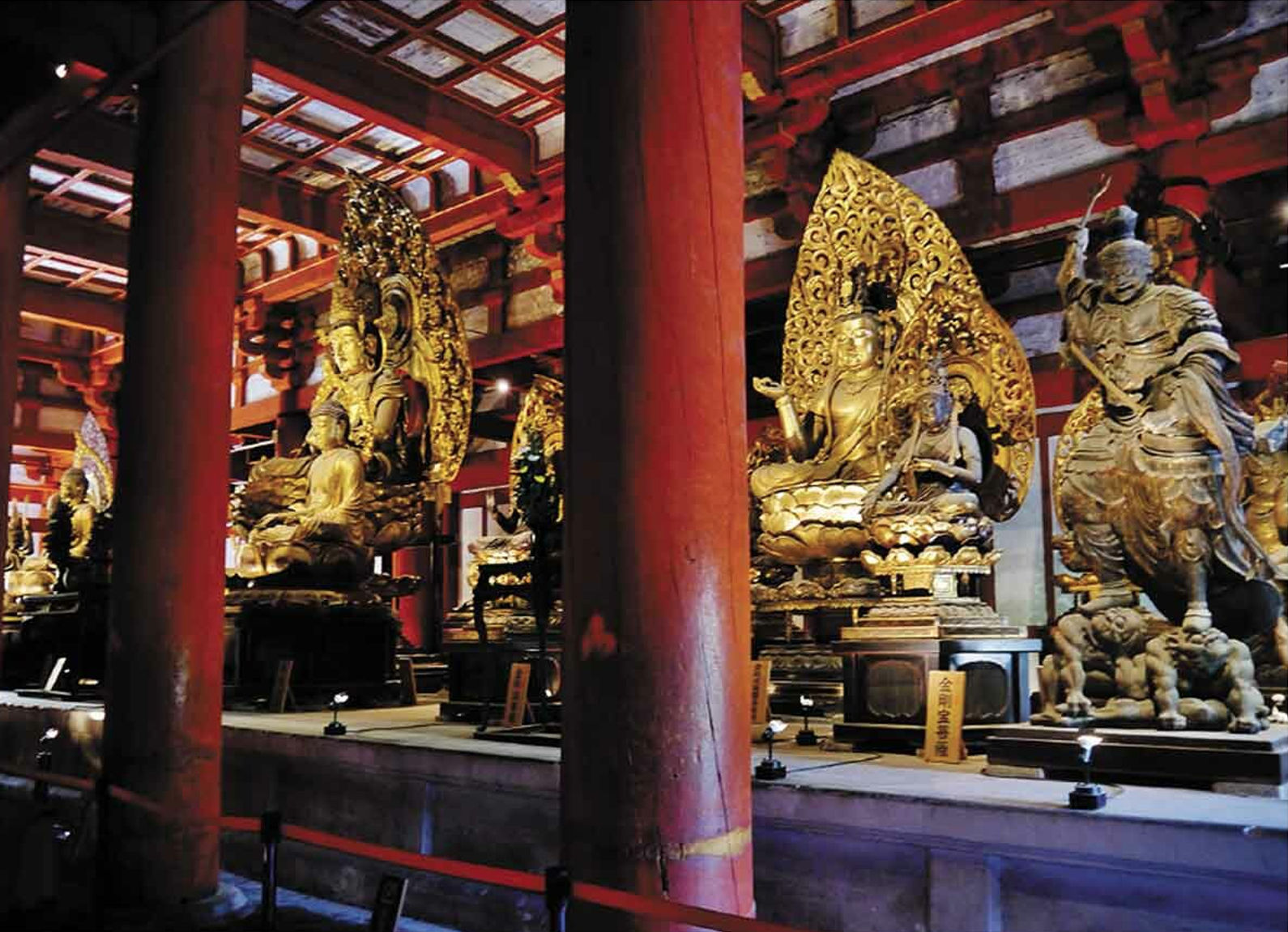

Fig 14

Part of the original 21 mandala statues at the Toji temple in Kyoto (Wiki commons). Photo & caption from Wang, S. (2021). Museum coloniality: displaying Asian art in the whitened context. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 27(6), 720-737.

Fig 16

Seated Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara (Guanyin) of Water-Moon Form, Liao Dynasty, 907-1125

Wood, gesso, and pigment with gilding; Chinese; On View, Gallery 231 SLAM (Photos by Cindy Bu)

To say the least, even if not considering the choice of art objects in the exhibitions of art museums, the display of Asian antique craftworks, especially those related to the Buddhist religion, also has underlying issues in Western museums. Due to the lack of understanding of the cultural meaning behind Buddha sculptures, the curator in some art museums distort the artists’ original intention by depriving their original context. For example, according Shuchen Wang, Émile Guimet, impressed by the beauty of manadala sculptures of Esoteric (Mantrayana) Buddhism at the temple Toji, commissioned a set of replicas as he was not able to get the original in his museum Musée Guimet. In Kyoto, the sculptures are purposefully positioned higher than the viewers’ eye level and fenced away to distance the viewers (Figure 14). A sense of serenity and awe is thus enticed by facing the unapproachable ‘god.’ In contrast, in Musée Guimet, to fit the set of Buddhist sculptures into a modernist style art museum with limited space, the statues are crammed into a single table with the original fence removed. Additionally, the visitors are allowed to look closely at these Buddhist sculptures at eye level, thus eliminating the deliberate distance maintained in the original condition (Figure 15) (Wang 12–13). This single act of removing the context undermines the divinity of these sculptures, immediately turning the viewing experience secular. The reverence of the ‘god’ maintained by the distance is diminished right away. While Musée Guimet is an art museum in France, the art museums in America also have a similar issue. One of my peers at Washington University in St. Louis also recalls a similar experience of seeing crammed Buddha sculptures in a single room in the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) in her hometown Dallas, Texas.

In its display of Buddhist sculptures, SLAM provides a good model and a potential solution to alleviate the issue of context removal in modern art museums. SLAM utilizes the long corridor to frame the Buddhist sculpture in the end room or posits the Buddhist statue at the back wall of the large room and frames it similarly with the door frame (Figure 16). The natural distance created by the corridor and the large room, and the framing of the sculpture enable the visitors to approach the statue from a far distance. These Buddhist sculptures are also placed on the pedestal, raising them from the ground to mimic the original context. The visitors can thus spot and appreciate the Buddha at far and look at the delicate craftwork in detail simultaneously. Both the artists’ original intention and skillfulness are addressed, telling a complete story of the art object.

Addressing the problem and the prospective solution of the position of Asian galleries, the choice of inclusion, and the way of displaying the Asian artworks, I wish that continuous recognition and awareness are called to the effort needed on the discrimination against Asian artworks in the United States. There are both spatial and financial limitations to the art museum. It is also really hard for the curators to balance every concern and provide a relatively objective and fair world view of artworks of different cultures under a single roof. And it is just impossible to be entirely unbiased. However, I still believe there is a potential that the presentation of the Asian artworks can achieve a better state with ongoing efforts. There is a way through all these limitations with the potential solutions I propose in this paper.

By adjusting the layout of the Asian artworks, adding more contemporary arts especially in nationally recognized public art museums, and being more deliberate in transferring the artworks’ original meaning, U.S. art museums have the potency to tell a better story of these Asian artworks. Museums are essential “institutions for representing people through object” (Ward 5). These public institutions, especially the encyclopedic art museum, hold the responsibility of presenting all cultures to the people in their nation. Through a proper representation of non-western cultures to have them stand on their own, the stereotype and the discrimination toward Asians and non-westerners might also be reduced in the US society. As an education site, the art museums ought to turn their task into an opportunity to try to help with social issues. Through the non-homogeneous representation of Asian artworks, the US citizen might also appreciate the Asian population as independent individuals rather than a predetermined character type. With a better presentation of the Asian arts in United States art museums, the United States can achieve not only better education of arts to the public but also develop a better society.

[1] Even for the special exhibition “Japan: A History of Style,” the “Exhibition Object” part of the page for this special exhibition shows only three objects from around the 10-11th century, one object from the early 14th century, and one object from before 1952, none for the 21st century (Figure 10). In some sense, it still chooses to share the “antique” facet of this exhibition rather than recognize its modern aspect.

Works Cited

Alexander, Aleesa Pitchamarn. “Asian American Art and the Obligation of Museums.” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021, doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11465.

“Asian Art.” Metmuseum.org, metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/asian-art.

Clarke, David. “Contemporary Asian Art and its Western Reception.” Third Text, vol. 16, no. 3, 2002, pp. 237–242, doi.org/10.1080/09528820110160673.

“Chinatown Art Brigade.” Asian Arts Initiative, asianartsinitiative.org/artists/featured-artists/chinatown-art-brigade.

Preziosi, Donald. “Brain of the Earth’s Body: Museums and the Framing of Modernity,” in Museum Studies: An Anthology of Texts edited by Bettina Messias Carbonell. Blackwell, 2004.

“Floorplan.” Saint Louis Art Museum, 18 Apr. 2022, slam.org/floorplan.

Hoffman, S. K. “Practicality and Value: Historical Influences on Museum Studies in the United States.” ICOFOM Study Series, 46, 2018, pp. 113–130, doi.org/10.4000/iss.1003.

“Japan: A History of Style.” Metmuseum.org, metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2021/japan-history-of-style.

Jones, Anna Laura. “Exploding Canons: The Anthropology of Museums.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 22, 1993, pp. 201–220, jstor.org/stable/2155846.

“Mission and History.” Saint Louis Art Museum, slam.org/mission-history.

“Real and Imagined Landscapes in Chinese Art: Exhibitions.” Saint Louis Art Museum, slam.org/exhibitions/real-and-imagined-landscapes-in-chinese-art.

“Seated Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Guanyin) of Water-Moon Form.” Saint Louis Art Museum, slam.org/collection/objects/36928.

Lee, Sonya S. “Introduction: Ideas of Asia in the Museum.” Journal of the History of Collections, vol. 28, no. 3, 2016, pp. 359–366, doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhw019.

“The Met Collection.” Metmuseum.org, metmuseum.org/art/collection.

“The Monochrome Mode in East Asian Art.” Saint Louis Art Museum, slam.org/exhibitions/the-monochrome-mode-in-east-asian-art.

Ward, Logan. “Museum Orientalism: East versus West in US American Museum Administration and Space, 1870-1910.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, 1 Oct. 2021, cmsmc.org/publications/museum-orientalism.

“Wang Guangyi.” Wang Guangyi - Opera Gallery, operagallery.com/artist/wang-guangyi.

Wang, Shuchen. “Museum Coloniality: Displaying Asian Art in the Whitened Context.” International Journal of Cultural Policy, vol. 27, no. 6, 2021, pp. 720–737.

Wilson, Emily. “A Final Show Honors the Legacy of a Bay Area Art Legend.” Hyperallergic, 6 Oct. 2021, hyperallergic.com/681445/hung-liu-golden-gate-de-young-museum.

Cindy Bu is from Shanghai, China and studies in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis.