Tweet! Tweet! We Can Hear the Birds Again: The Impact of User-Driven Platforms on Climate Conversations and Public Action

Isa Lee

Sept 2021

Clear skies in LA! Drunk elephants in Yunnan, China! Dolphins and swans in the Venice canals! In March of 2020, when COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization, the world saw a surge in activity across virtual platforms. As students finished their senior year in the silence of their own bedrooms and people were separated from their loved ones, video-conferencing and social media platforms provided some connection in a time filled with unanswerable questions, extreme uncertainty, and physical isolation. One of these platforms, Twitter, saw a rise from 152 million daily users at the end of 2019 to 166 million in the spring of 2020 (“Twitter sees record number of users…”). While one can find tweets spanning just about every category imaginable, this paper will examine the surge in climate- and environment-related conversations on Twitter during the spring months of 2020. In many ways, I will reveal that social media has driven conversations that portray a false sense of progress and “healing.” However, findings also will display how conversations reveal a sense of acknowledgement of a climate problem and, perhaps, hope for a healthier future. In this paper, I will argue that user-driven platforms drive the “gap” between acknowledgement and action.

Therefore, this paper demonstrates that translating climate conversations into public action will demand addressing the role of emotion on the spread of media and the additional components of social platforms that may negatively impact the public’s understanding of climate science.

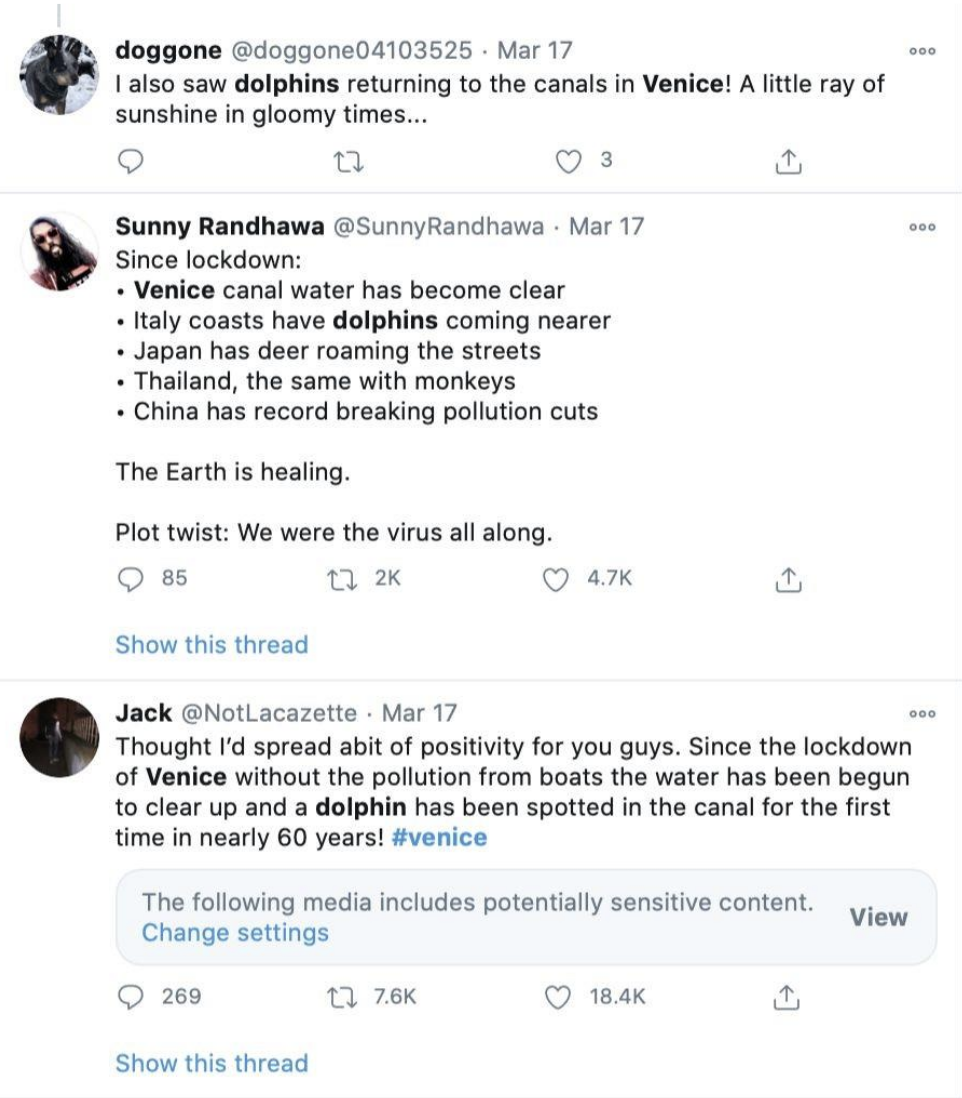

On March 17th, news of dolphins returning to the Venice canals surfaced on Twitter. Gaining more than 1.3 million views, the original tweet includes a thirty-second clip of a dolphin emerging to the surface through murky water alongside two photos. This story sparked conversations across social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook even after it was deemed fake by National Geographic three days later. In her chapter titled “You won’t believe how co-dependent they are: Or: Media hype and the interaction of news media, social media, and the user,” author Vivian Roese defines incidents such as these as “accidental media hypes” — the “natural, user-generated news waves” that are often “triggered by any kind of deep emotion” (316). Considering the impact of emotion on the Venice dolphins case reveals how a cascading effect can occur for a story that was never true to begin with. As defined by Oxford Languages, emotion is an “instinctive or intuitive feeling as distinguished from reasoning or knowledge,” which implies that it materializes naturally and is inaccessible to our conscious mind. Thus, it is pertinent that we recognize our media consumption as filtered by our unconscious. Roese emphasizes that media hype “can be triggered by more emotions than pure outrage — as in the case of scandals — but also by positive reactions,” like “identification,” “pride of belonging to a group” or “happiness and relief” (320). With the Venice canals well-known for their polluted, congested waters, the sense of “happiness” and “relief” were felt by people across the world who were enamored by the news of precious wildlife returning to this famous destination.

Thus, as people searched for comfort and encouraging news in a time of global turmoil, perhaps it should be no surprise that the story was so widely shared.

Examining how users’ emotions manifest in retweets of the original story reveals the power of a social platform to spark conversations amongst users. One user writes in his caption, “thought I’d spread a bit of positivity for you guys,” while another shares “a little ray of sunshine in gloomy times” (@NotLacazette; @doggone04103535). Here, we see the "happiness" and "positivity" that Roese deems as media hype triggers. Users saw the news of nature flourishing as a silver-lining — namely, a “ray of sunshine.” However, more notably, many reshares of the story (and responses to the numerous similar stories about rare animal sightings during lockdown) included even stronger expressions such as “The Earth is healing” (@SunnyRandhawa). It may be true that nature has triumphed at the temporary retreat from polluted waters and roaring city streets; however, declarations such as these on social media may reach hundreds, thousands and even millions of people, depending on how strongly the post resonates with other users. While tweets like this one also reference this silver lining, they may also contribute to the spread of a false sense of “healing.”

While Roese’s discussion provides a psychological perspective on the spread of media, Jaco Barnard-Naudé provides a complementary lens rooted in the philosophy of the human mindset. In his article titled “We Must Be Able to Get Used to the Real,” Barnard-Naudé illustrates a framework that is helpful to this study of climate conversations:

We have preferred, indeed insisted, that the Real come to us in mediated and mediatized form exclusively and thus as necessarily sanitized… not only so that we can wash our hands of the Real but also so that we won’t have to get our hands dirty with the Real in the first place. (219)

When Barnard-Naudé refers to "the Real," he is referencing the reality of COVID-19; however, as two global health crises with roots in human destruction, I believe that "the Real" can also represent the reality behind the state of our climate. From this perspective, perhaps a reason for why the Venice dolphins tweets (and similar stories) were so widely shared was that they were the epitome of news in this "mediated" and "sanitized" form. As Roese foregrounds the danger of users serving as “some sort of private gatekeeper who decides how newsworthy or shareworthy a piece of information in their newsfeed is,” Barnard-Naudé suggests that rather than pure emotional desires, our avoidance of the Real actually may be deeply rooted in the human mindset. In combination with the power of media algorithms, these are factors that must be considered when studying how the public’s understanding of climate change can be constructed and shifted by the media itself.

Analyzing how news outlets cover these stories is also helpful to understand the trajectory of an “accidental media hype.” Beyond direct retweets, the story quickly spread to other platforms like Instagram and Facebook as it was covered by various news sources. With a deeper look at a March 18th tweet from Travel + Leisure, one notices that the headline is framed in a positive light to entice and excite readers with the use of the phrase “beautifully clear” to describe the unpolluted canal waters and an engaging photograph. While this observation may seem insignificant, Roese clarifies that “media hypes” are often “accelerated” by journalists and news coverage, even when “it was the user who created it, without necessarily intending to” (317). News sources know the impact of emotion on the success of news stories and the “limited attention span of the user scrolling through their infinite newsfeeds,” and thus, utilize this to their advantage by creating what Roese refers to as “snackable content” (324). For example, a Bloomberg headline from April 10th announces, “With Humans in Hiding, Animals Take Back the World.” This headline succeeds at standing out in a sea of other far more dispiriting news. Roese also mentions that news sources are aware that algorithms are adept at detecting “cheap click-baiting,” so journalists play a fine line of utilizing the framing effect to entice users while not crossing the boundary line into fake news territory (324). As the “lines between social media and news media seem to be blurring,” analyzing headlines that appear on these social platforms emphasizes the importance of understanding how social media has “reshaped the way we consume information” (Roese 321, 323). Thus, in regards to Barnard-Naudé’s framework, we must recognize how being continually presented with distorted versions of the Real — through exaggerated and framed headlines and carefully constructed "snackable" content — may unconsciously shift our understanding of the Real itself.

The Venice dolphins story was one of many that was deemed fake by National Geographic on March 20th in an article titled, “Fake animal news abounds on social media as coronavirus upends life.” The article revealed that the video was taken over one-hundred miles away at a port in the Mediterranean Sea, where dolphin sightings are not uncommon. National Geographic also debunked news of swans in the canals and the story that a group of elephants had “passed out in a tea garden” after they broke into a village in Yunnan, China and got “drunk off corn wine” (Daly). As stated by Erin Vogel (a Stanford University social psychologist and postdoctoral fellow) in the National Geographic report, the belief that nature was rebounding during a time of crisis “could help give us a sense of meaning and purpose.” As emphasized earlier, this “meaning” and “purpose” that Vogel refers to are driving emotions related to the spiraling of content.

Shortly after National Geographic’s article was released, the “nature is healing” meme ignited. In short, the #natureishealing and #wearethevirus trends aim to "poke fun at" the spread of these fake stories, as well as the abundance of other outrageous animal sightings. For example, one user posts a picture of dinosaurs in Times Square referencing nature’s return “for the first time since 65,000,000 BC” (@stpeteyontweety). Another user writes, “Wildlife finally returning to Thames” alongside a picture of a giant, floating rubber duck. With supporting evidence that she includes in her study from other researchers, Roese reveals that “irony, sarcasm, and mockery are common stylistic devices in social media in order to criticize,” where users “[make] fun of the way the press attempted to manipulate them” (320, 318). While I believe the “nature is healing” trend was created to spread good in dark times, I also observe how sarcasm and meme content allows one to veil any disappointment (of finding out the truth) and to avoid acceptance of reality. Thus, we may see how meme content that is intended to be humorous and relatable can also be part of this cascading effect.

It is valuable to note, however, that the sarcasm in these “nature is healing” memes also demonstrates a more serious notion — the sense of acknowledgement for the fact that indeed nature is not actually healing and that there is a problem at hand. In fact, many posts even directly state, “we are the virus.” However, we see that this acknowledgement has not led to any further action. Here, I introduce another statement from Barnard-Naudé, which provides insight on some components of this "gap" between acknowledgement and public action:

We have been, for some time, resisting, defending against, the Real. It is not that we have not been fascinated or fixated upon the Real, quite the contrary. But we have most constantly not been able to "get used to the real." (218)

Conversations across Twitter and other platforms demonstrate that perhaps there isn’t a lack of acknowledgement of a problem; instead, it is that we are unable to accept the problem as a real and urgent problem. Perhaps it is natural that we filtered climate-related news largely by what was exciting to us—the “LOLs, the awe factor, the weird-but-true and freaky curiosities of life” (Roese 316). However, the verbs “resist” and “defend” to describe our relationship with the reality behind climate change would imply a deeply rooted unease and reluctance — something driven by more than an excusable filtering due to our temporary emotional desires. In analyses of the “nature is healing” trend, it seems there is some level of public acknowledgement, but in a way that lacks sincerity and exhibits a resistance towards addressing reality.

Other climate-conversations from this spring demonstrate a sense of acknowledgement perhaps more directly than through memes. For example, at the beginning of the lockdown, people in Los Angeles came to Twitter with the topic of imp-roved air quality. Similarly to the animal sighting stories, a user also shared this as a “bright side to the stay at home order” (@lokraankiin). As people saw a change in air quality in their own cities, they turned to their phones to share the news. “My lungs don’t know how to act,” says one user (@_KSLTweets), while another shares, “Okay… it’s actually crazy how tropical certain parts of LA smell when the air quality is at it’s cleanest it’s been in years” (@paulgvbriel). In addition to Los Angeles, tweets such as these were seen in reference to many other of the world’s most polluted cities. As people are granted a glimpse into a reality that could be, there may be more of an acknowledgement that climate-problems are human-driven.

Evidently, a user-driven platform like Twitter can be powerful in many ways to spread conversations that are important; however, with users’ focus directed only on the present moment, there is the potential for a lack of acknowledgement for the long term. There is something certainly powerful about instant shareability and mobilizing current conversations. In effect, this approach is part of what makes Twitter’s platform so successful. However, we must remember that social media manifests with an exclusive focus on the present moment. Twitter themselves lead with this approach, such that the Twitter "About" page features the tagline, “Twitter is what’s happening in the world and what people are talking about right now.” In Jon Naustdalslid’s article titled “Climate change — the challenge of translating scientific knowledge into action,” he addresses this problem directly by stating “the distance between causes and effects is, moreover, increased by the fact that cause and effect are separated not only in space but also in time” (244). I believe that this “separation in time” is one of the factors that we must be analyzing when discussing how social media drives the acknowledgement-action gap. From a Barnard-Naudé lens, maybe it is that as soon as we set our phones down for the night, we can return to the comfort that comes with this “separation in time,” and consequently, any progress towards addressing the Real is forgotten; or, perhaps it is that what we believe to be the Real is just a filtered media representation that only continues to be diluted.

With content either handed to us in this "mediated form or otherwise fueled by our own emotions and unconscious biases, it becomes easy to overlook the fact that people are impacted in very real ways. Often, the stories that we’re reading are across the world from us in countries that we may have no connection to. This is powerful to us as consumers, allowing us to feel as though we’re part of something much greater than ourselves. However, sheer physical distance from the stories we’re reading also means that we can read a story, feel impacted by it, and then be able to never think about it again. It is important to address that this applies to news that we consume in all capacities — not just news stories on social media like those that I have discussed in this paper. For example, after reading a New York Times article about the fires in Australia earlier this year and seeing families and wildlife fleeing the flames, one may have prayed for the health and safety of the first responders and evacuees. However, months later, when we no longer see it in the Top Stories page of Apple News or on television, we are able to forget. This is problematic, as Naustdalslid reminds us that “the problem [of climate change] is indeed real and exists irrespective of our knowledge about it” (243). Without any form of accountability, we are permitted to remit to the comfort of our resisted Real.

I have designated sheer physical distance, detachment from a time frame, and the role of emotion on the spread of information as components of user-driven platforms that may contribute to the public perceiving climate change as a distant, “far-away” problem. The question that is now raised regards how we close this gap. Like Naustdalslid, I do not believe that there is any one simple answer to this question. However, his findings provide insight on some important factors to this question. He warns us that “the more society gets dependent on advanced and specialized knowledge, the more difficult it will be for non-experts to grasp and critically relate to this exponentially growing body of knowledge”; thus, “knowledge itself will not be enough to cause action” (248). Another gap is introduced here — one that is between “experts and ‘ordinary’ people (including politicians and decision-makers)” (248). Perhaps this emphasizes the need to approach the question of climate action from new perspectives. In support of my argument, Naustdalslid states that the “lack of climate action” is related to “the ways in which climate change interlinks with society” (243). In my analysis, I attempted to demonstrate social media’s impact on our modern society, and thus, I believe that this exploration of the media’s role in this gap is substantiated. Naustdalslid’s proposal is that we must “revisit the relationships between science, society, and policy” (243). I understand this to mean that it is not sufficient just to look at climate change as something we can combat with changes in government or through conversations among our world’s top scientists. Changes in government and policy don’t happen without the public’s support. I argue that social media can be used as a primary reference to better understand the public’s stance on issues and may also be the place that we can spark more serious conversations.

As social media grows as a tool for social activism, questions arise as to the viability and effectiveness of these platforms. While my exploration has primarily focused on the ways in which user-driven platforms contribute to widening the gap between acknowledgement and action, I do believe that these user-driven platforms can be a part of the answer to closing this gap as well. A step towards addressing the factor of sheer physical distance may be sparking local conversations in our own communities and within our own families. In regards to detachment from a timeframe, perhaps we must direct the public’s attention to see trajectories in relation to our own children, grandchildren, or any other loved one who will see on to the earth’s life farther than we will. Previous research and my findings reveal how easily conversations can spark and spread on a social platform. Thus, potential is discerned. Even as just a start, people are seeing with their own eyes the effects that decreases in pollution have on their cities, small communities, and the natural world.

Consider that 2019 was the second warmest year ever or search up the list of coastal cities that are expected to be underwater by 2050. There are so many conversations that we aren’t having enough right now — plastic ban lifts across the country, the abundance of one-time-use takeout containers, increases in single-passenger car use, decreases in public transportation use; the list could be never-ending. Addressing the Real is scary. Climate change is scary. But hiding away whenever life gets scary does not mean our problems do not exist, nor that the problem will go away with waiting. So let’s stop putting climate change on the back burner. Now, more than ever, is the time for action.

Works Cited

@_KSLTweets. “If you live in LA, it’s so noticeable how much better our air quality is currently. My lungs don’t know how to act.” Twitter. 30 Mar. 2020.

“About.” Twitter. about.twitter.com

Barnard-Naudé, Jaco. “We Must Be Able to Get Used to the Real.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, 53.3. 2020. 217-224.

Daly, Natasha. “Fake animal news abounds on social media as coronavirus upends life.” National Geographic. 20 Mar. 2020.

@doggone04103525. “I also saw dolphins returning to the canals in Venice! A little ray of sunshine in gloomy times…” Twitter. 17 Mar. 2020.

“Emotion.” Oxford Languages. Oxford University Press. 2020.

@lokraankiin. “hey bright side to stay at home order: LA has had good air quality the whole month.” Twitter. 30 Mar. 2020.

Lombrana, Laura Millan, and Eric Roston. “With Humans in Hiding, Animals Take Back the World.” Bloomberg Green. 8 Apr. 2020.

@Lukeyzy. “Venice hasn’t seen clear canal water in a very long time. Dolphins showing up too. Nature just hit the reset button on us.” Twitter. 17 Mar. 2020.

Naustdalslid, Jon. “Climate change —the challenge of translating scientific knowledge into action.” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 18:3. 2011. 243-252.

@NotLacazette. “Thought I’d spread a bit of positivity for you guys. Since the lockdown of Venice without the pollution from boats the water has been begun to clear up and a dolphin has been spotted in the canal for the first time in nearly 60 years! #venice.” Twitter. 17 Mar. 2020.

@paulgvbriel. “Okay…it’s actually crazy how tropical certain parts of LA smell when the air quality is at it’s cleanest it’s been in years, especially now that it’s Spring!!” Twitter. 29 Mar. 2020.

Roese, Vivian. “You Won’t Believe How Co-Dependent They Are, Or: Media Hype and the Interaction of News Media, Social Media, and the User.” From Media Hype to Twitter Storm. Amsterdam University Press. 2018. 313-332.

@roobeekeane. “Wildlife finally returning to Thames. Nature is healing.” Twitter. 29 Mar. 2020.

“Twitter sees record number of users during pandemic, but advertising sales slow.” The Washington Post. 30 Apr. 2020.

@stpeteyontweety. “Wow. This is New York today where the city’s streets are empty and nature has returned for the first time since 65,000,000 BC. The earth is healing, we are the virus.” Twitter. 5 Apr. 2020.

@SunnyRandhawa. “Since lockdown: Venice canal water has become clear. Italy coasts have dolphins coming nearer. Japan has deer roaming the streets. Thailand, the same with monkeys. China has record breaking pollution cuts. The Earth is healing. Plot twist: We were the virus all along.” Twitter. 17 Mar. 2020.

@TravelLeisure. “Venice’s Canals Are Beautifully Clear and Dolphins Are Swimming Through Its Ports As Italy’s Coronavirus Lockdown Cuts Down on Water Traffic (Video).” Twitter. 18 Mar. 2020.

Isa Lee is from San Rafael, California and studies in the College of Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.