Silencing the Mother Tongue: Identity Construction in Monolingual Higher Education

Siyue Han

Sept 2021

Introduction & Background

“English only, please!” was the request I heard most during my summer language program as an international student. Despite the temptation to use our home languages, we were strictly required to speak English only both inside and outside of the classroom to capture more opportunities for practicing English. In these special programs designed for language minority students, English remained the dominant language in use, although the class consisted of one teacher as the only native English speaker and everyone else as the second language (L2) learners. In this light, the dominant language is not decided by a simple majority rule. Tove Skutnabb-Kangas, a linguist and activist against language discrimination, observed that although monolinguals are actually the minority by number, “many of them belong to a very powerful minority, namely the minority that has been able to function in all situations through the medium of their mother tongue, and who therefore have never been forced to learn another language” (Skutnabb-Kangas and Phillipson). English — with its high academic and professional value — is one of these “powerful minority” languages.

Higher education is not immune to the social norms and power dynamics of mainstream societies. Other than second language programs, this “English-only” policy also occurs on the monolinguistic US college campuses. A Duke University assistant professor in 2019 sent an email asking international students to “commit to English 100% of the time” when they were in the department building and keep in mind “unintended consequences” of speaking Chinese, which she referred to as potential loss of academic and internship opportunities. This controversial email was later retracted by the professor after the backlash from the international student community (Cheung). But still, this incident illustrates the powerful position of English as the standard language at school and work in the US. One respondent directly explains his or her reason of using L2 by saying “it’s English and I live in the US.” Minority languages face the threats of being ignored, silenced, or marginalized by the dominant language, resulting in a lack of language diversity in most US colleges. While the minimized use of students’ home languages does help familiarize them with their L2 learning, it also impacts their construction of identities. After all, language, culture, and identity are all intricately connected and intertwined with one another.

Research Objectives & Methods

In this research, I will investigate the cultural, social, and cognitive influences of monolingualism on the identities of bilinguals and second language learners (more specifically, the ESLs). Discussions will be positioned in the context of higher education in the US. The field has not yet reached a consensus on who should be classified as “bilinguals.” This paper adopts a broad definition of bilinguals and will focus on US college students who “use” at least two languages, with a particular focus on L2 students whose native language is a minority language, and whose second language is English. “Use” includes reading, listening, writing, and speaking the language in a range from beginner to proficient level.

In terms of research methods, I will integrate insights from the existing literature, as well as my discoveries from an informal survey to shed more light on how a monolingual environment, in reality, impacts identity construction. The survey was first out on December 1, 2020, and received 83 responses (the final sample size) by December 9, 2020. The respondents are predominantly bilinguals, multilinguals, or second language learners from the first-year college writing program at Washington University in St. Louis or other US institutions.

Affiliation with Heritage Culture

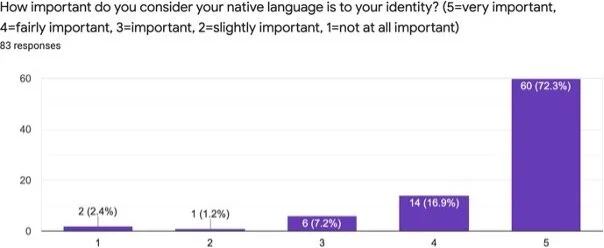

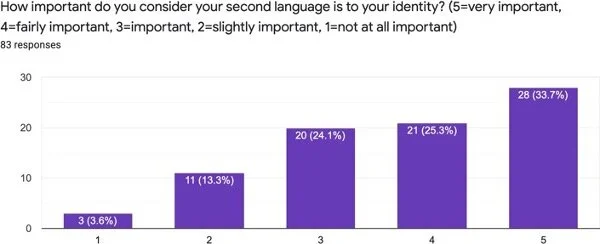

Above all, I want to highlight the significance of the native language in identity construction, which is evident in the comparison between Figures 1 and 2 from the informal survey. A majority of respondents rated their native language as “very important” to their identity, while their second language is valued less, with only a third of respondents reported “very important.”

Figure 1

Figure 2

Given the great importance of native language to identity, the constantly minimized use of native language will likely influence their sense of identity by changing their affiliation to heritage culture. This impact is particularly visible in cases where students’ home language is a minoritized language. On the first day of my study abroad experience in the US, we international students picked an English nickname that was easy to pronounce by native speakers. But in general, we shared a common name called “ESL” (English as Second Language) students. This somewhat problematic name detaches us from our mother tongue and emphasizes our identity always as a “learner” rather than an “owner” of the dominant language. While the common belief regards language acquisition as a social or cultural process, Dr. Ofelia García, a professor specializing in multilingualism and education of language minority students, also mentioned a genetic aspect in her book: “Second language learners were seen as just that, never able to compete with ‘native speakers.’ This ‘thickening’ of the language identities of ‘second language’ speakers for whom the dominant language could never be ‘first’ is related to the myth that there is a ‘genetic’ ownership of language” (García and Li 54). This genetic perspective helps explain why our first language is metaphorically called our “mother tongue” or “native language” — it is a right we inherit and own from birth.

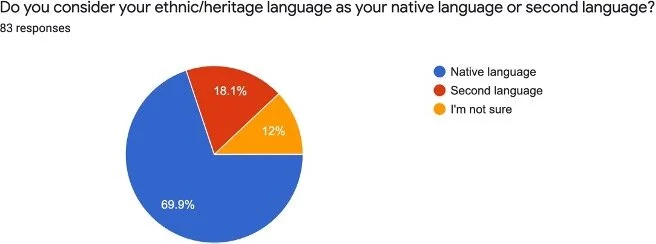

Indeed, people like to associate their native language with their birth and heritage. In the survey results, a large proportion of respondents consider their heritage language as their native language (Figure 3). And a survey respondent even clarifies in the comment that he or she still counts the non-English language from birth as L1, despite currently more frequent and fluent use of English.

Figure 3

However, the heavy emphasis on the linkage bet-ween birth and language identity solidifies the belief that L2 learners are “never able to compete with ‘native speakers,’” further exacerbating their struggle with language ownership issues. Worse, this belief could be internalized and impair L2 students’ confidence and self-esteem. They might be more reluctant to use their L2 for fear of competing with native speakers. With the repression of using L1 and desire for ownership of English, L2 students are thus more prone to construct new identities around the English culture, which may give rise to conflicts with their heritage cultural identities. One’s relationship with their native language is closely related to his or her affiliation to heritage culture. Most of the survey respondents concur that using heritage language is a way to practice their ethnic culture. Jin Sook Lee’s research on second-generation Korean American university students has shown that maintenance of heritage language greatly shapes one’s sense of identity and self-esteem, in the sense that higher proficiency in heritage language helps build a greater degree of bicultural identity (qtd. in Shin 105). In conclusion, the enforced detachment from L2 students’ first language can weaken their cultural identity development.

Social Behavior

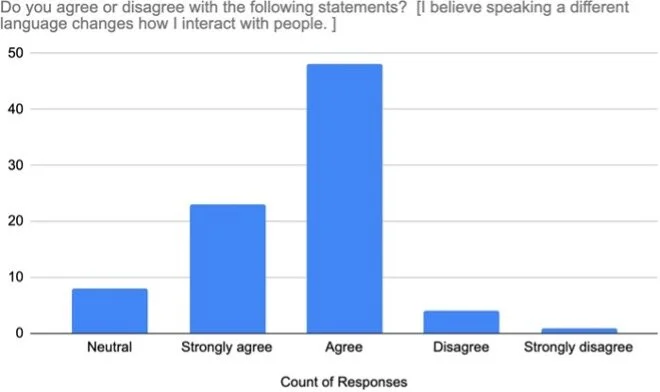

Lasting, frequent interaction with the second languages can give rise to newly constructed or conflicted identities by altering social behavior. I used to naturally reply to people’s compliments with “No, no” (as “Mei-you, mei-you” in Chinese). Later I realized that my American peers would respond with “Thank you” or “I'm glad you like it.” In the Chinese language, the reply to a compliment is usually rejection to show modesty and discretion even though it is well-deserved, while in English, people would willingly take that compliment and express their emotions. Subtle distinctions in language habits like this are largely derived from cultural differences, with Chinese culture stereotypically more reserved and circumspect and English-speaking culture being more individualistic and expressive. This is not a peculiar case that only happens to me — in fact, most of the survey respondents agree that speaking different languages can alter their way of interaction (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Figure 5

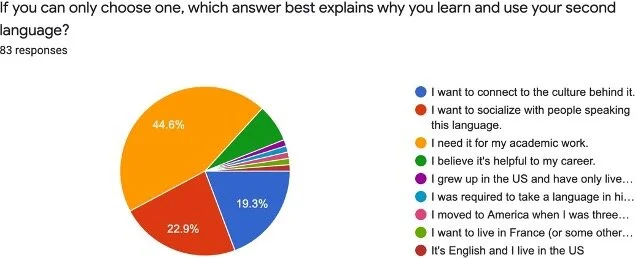

In a US college, the bilinguals naturally prefer using English to socialize in a more effective manner, with the desire to identify with their peers. When asked about the main reason for learning and using L2, around 23% of respondents expressed the social function of their second language (Figure 5). Socially pressured in colleges, L2 students face two options: first, they could adopt what is called “native-culture anchoring,” mostly interacting with other L2 students to smoothly transition into the new culture and seek attachment to their home culture (Ortaçtepe 172), but they would still struggle with their minority identity, feeling unable to socially adapt to the host culture. Or they could use the host language and blend into the social circles of local students. In this process, nevertheless, they would gradually modify their social interactive behaviors including their language usage, gradually creating a personality or identity that fits in the host culture. However, this notion of always trying to “fit in” a new culture is problematic in itself, since cultural communication ought to be a mutual process. With the increasing internationalization of higher education, colleges nowadays have a more diverse student body with multilingual backgrounds. L2 students, as a contributor to the “diversity” of colleges, are supposed to bring multicultural and multilinguistic perspectives but are struggling to assimilate their identity into the host culture.

Self-expression

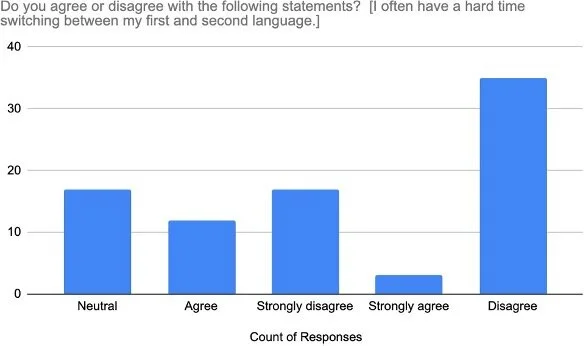

One of the primary functions of languages is to express emotions and thoughts. Some survey comments indicate that it is hard to fully articulate their thoughts in-depth with only L2. I personally also have similar experiences: when I was trying to analyze an abstract concept or write emotional prose, I tend to think in my native language and then mentally translate my thoughts into English. To identify the relationship between bilingualism and self-expression, a study done by Antonela Bakić and Sanja Škifić discovered that most of their research participants considered their first language as “more emotional,” meaning L1 is more helpful and effective in expressing emotions like love and anger. The researchers also illustrate the intricacy of this relationship by highlighting the considerable variations across bilinguals with different language acquisition processes. Language usage is often connected to the settings where the language is acquired or most frequently used. For example, counting is mostly used in L1 as learned from an early age. Contrarily, I will most likely use English (my L2) to construct ideas about American history, since I learned about the historical events in an American classroom. Despite individual differences, the researchers concluded that all the bilingual participants use both languages for emotional expression and cognitive processing. Whether they are aware or not, most L2 learners undergo code-switching processes of the two semantic systems, yet the difficulty of code-switching differs by personal factors. A research study on first-year College Writing Programs' bilingual students shows that while language minority students prevalently indicate their need to rely on two languages to express ideas, “home language and school language (i.e., English) are felt to coexist comfortably at various levels.” Interviewees report, “English is understood to work in parallel with their mother tongue” (Chiang and Schmida 19). This research finding reveals the possibility of keeping students’ first and second language identities separate and intact. As a matter of fact, the survey respondents also find the influence of code-switching minimal, as most people do not see it hard to switch between two languages (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Regardless of the complex personal factors that involve unique language acquisition settings, the impact of bilingualism on self-expression contributes to the process of identity construction. Partly influenced by social and cultural factors, identities are mostly constructed around people’s own thoughts and perceptions. As shown in Figure 5, nearly half of the respondents use their L2 mainly for academic purposes. In US colleges with English as the primary language of instruction, L2 students rely on their second language to express their thoughts in class participation and academic assignments. In language attrition processes where L2 takes over L1 on a daily basis, students could undergo changes in their thinking styles as their L2 becomes the dominant language in use — which then exerts impacts on their formation and development of identities. For instance, they might unconsciously repress their expression of emotions and adopt a more logical mindset when using L2 only.

Discussion & Conclusion

As mentioned above, language is complicated with numerous factors. The survey respondents all have different proficiency levels in each language, approaches, and motives of learning their L2. Some had multiple first languages; some learned their second language on a trip to France; and some used their first language only for talking to their parents. These individuals will surely present very different opinions about their bilingual experiences. Therefore, the survey results used in this research only serve informal purposes, because of too many confounding variables that are hard to control.

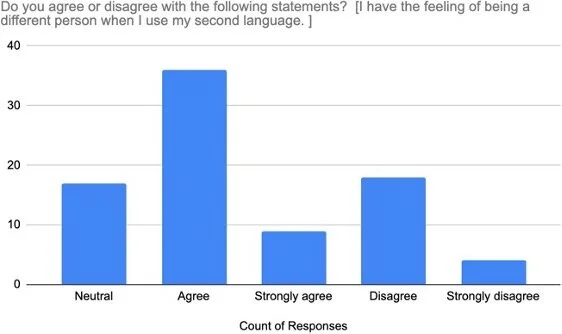

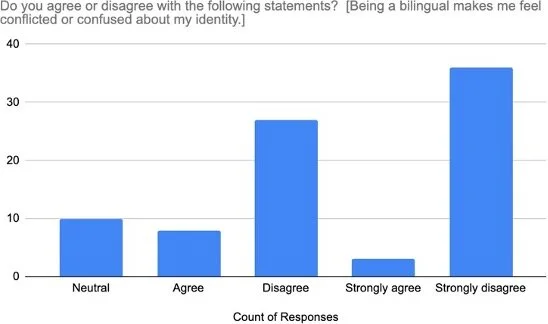

The common conclusion is that the extent to which L2 students’ identities are influenced by language varies among individuals. This varying degree of impact among individuals could have implications for how to form compatible language identities without losing the heritage identity. As presented in Figures 7 and 8, while a significant proportion of respondents experienced identity changes from switching languages, they still believed their identity was not conflicted or confused. This interesting result reveals their ability to balance their bicultural identity. Future studies can examine these subjects closer to find implications for reconciling two language identities.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Despite the multilingual nature of the world, most institutions worldwide set up curriculums taught only in the dominant language of the state. The discussions on diversity and inclusion of higher education commonly focus on racial/ethnic, cultural, and gender identities. Often perceived as a “derivative” to these aforementioned identities, Language identities are largely ignored due mostly to the benefits of monolinguistic policies. Admittedly, monolingual practices can increase communication efficiency through a standard language. But people should be cognizant of the consequent impacts on identity construction that result from altered affiliation to heritage culture, social behaviors, and thinking styles. In essence, silencing of the mother tongue is an outcome of both personal choice and societal force. Universities should celebrate and respect diverse language identities, building an inclusive environment where individuals will have the freedom to choose which attitude they will adopt towards their L1 and L2.

Works Cited

Bakić, Antonela, and Sanja Škifić. “The Relationship between Bilingualism and Identity in Expressing Emotions and Thoughts.” Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 22:1. 2017. 33-54.

Cheung, Helier. “Duke University professor removed over ‘Speak English’ email.” BBC News. 28 Jan. 2019.

Chiang, Yuet-Sim D., and Mary Schmida. “Language Identity and Language Ownership: Linguistic Conflicts of First-Year University Writing Students.” Enriching ESOL Pedagogy: Readings and Activities for Engagement, Reflection, and Inquiry. Psychology Press. 2002.

García, Ofelia, and Wei Li. “Language, Bilingualism and Education.” Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. Palgrave Pivot. 2014.

Ortaçtepe, Deniz. The Development of Conceptual Socialization in International Students: A Language Socialization Perspective on Conceptual Fluency and Social Identity. Cambridge Scholars. 2012.

Shin, Sarah J. “Bilingualism and Identity.” Bilingualism in Schools and Society: Language, Identity, and Policy. Routledge. 2012.

Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove, and Robert Phillipson. “‘Mother Tongue’: the Theoretical and Sociopolitical Construction of a Concept.” Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties. De Gruyter. 2012.

Siyue Han is from Changzhou, China and studies in the Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis.