@Aphrodite: Tracking Women’s Objectification from Venus pudica to Instagram

Micah Sandman

1. INTRODUCTION

In this essay, I argue that a paradigm of the objectification of women in classical Western art has shifted to a paradigm of self-objectification on social media. For the purposes of understanding how agency has been incorporated into the visualizations of the body in this essay, I present three stages of the so-called ideal woman: classical, modern, and ‘postmodern.’ [1] I critically examine Kylie Jenner, the paradigmatic subject of Instagram. I also explore the postmodern, mainstream feminist lingerie brand Aerie. Next, I discuss promotion of the female body and the fluid, self-objectifying creator-viewer dynamic through a discussion of thirst traps. I question the tie between beauty and innate personal morality, which leads to my critique that essentialized woman’s virtue ethic is conditioned upon physical beauty. I end by challenging the fact that aesthetic beauty remains an exclusive and stubbornly consuming value of our Western capitalist society.

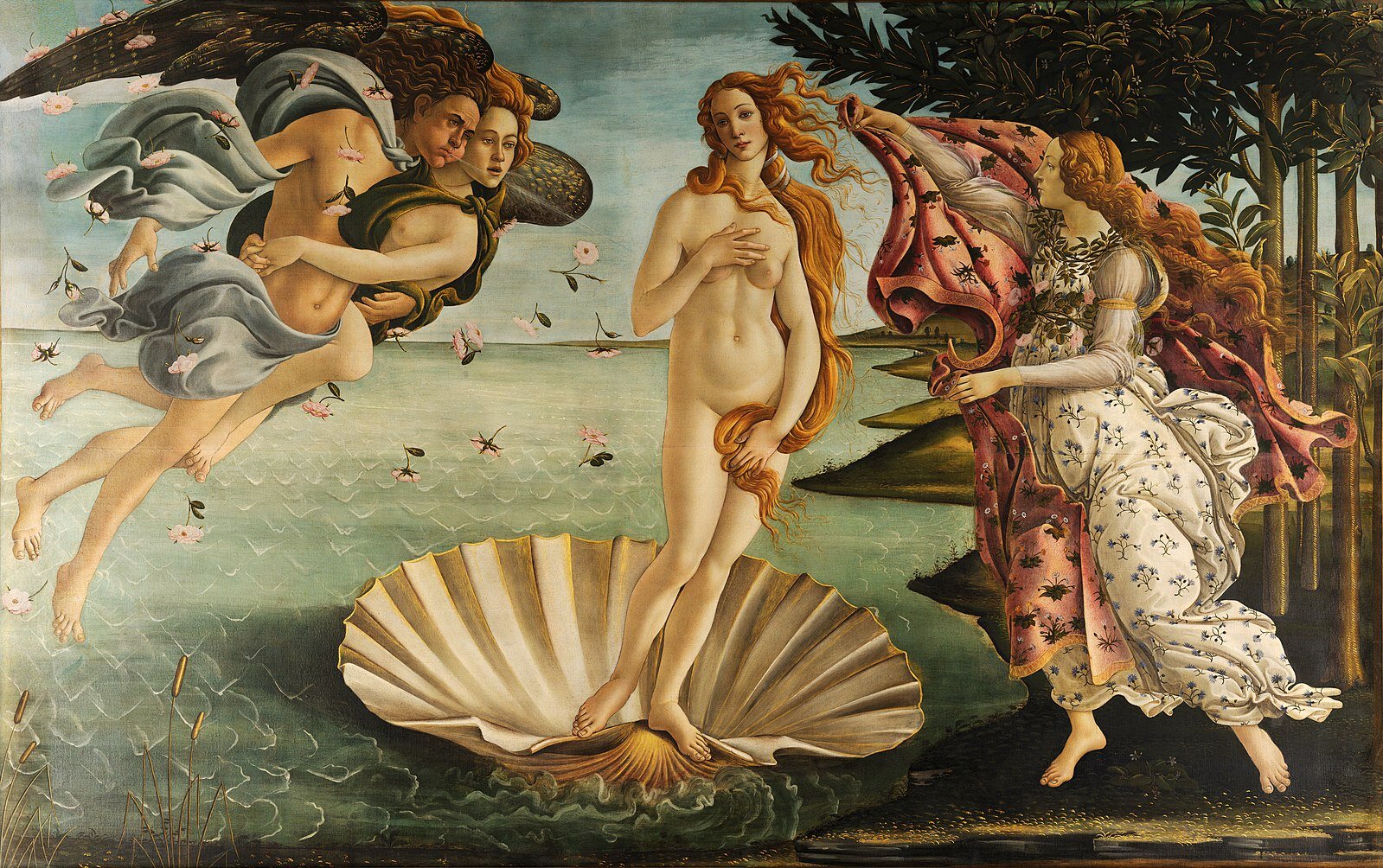

Birth of Venus. Sandro Botticelli. 1485 ca. Tempera on canvas.

2. ORIGINS OF THE IDEAL: OBJECTIFICATION THEORY AND THE VENUS PUDICA

The most famous representation of the female body in the classical Western art tradition is the Venus pudica, the depiction of an idealized naked female covering her pubis with her hand. This form was first depicted and “mainstreamed into western culture” by Praxiteles in the 4th century BCE with his statue Aphrodite of Knidos (Salomon 70). This pose came to be represented by many famous artists including the likes of Bosch, Van Eyck, Titian, Rembrandt, Botticelli, Renoir, Manet, Matisse, and Picasso. I chose to ground this framework with an initial discussion of the Venus pudica because, due to the limited and reflexive canon of Western art, “Praxiteles’s Aphrodite stands as the paradigmatic canonical work of the western world” (Salomon 70). Yet beside the fact that Western art recycles classical and biblical imagery, what makes Venus pudica the foundational example of visual female objectification? To answer that question, I must engage the work of philosopher Martha Nussbaum.

In her 1995 article “Objectification,” Nussbaum broadly imagines objectification to occur when a person treats or sees another person as a thing or an object. Nussbaum defined seven important aspects of objectification, including “instrumentality,” “denial of autonomy,” “inertness,” “fungibility,” “violability,” “ownership,” and “denial of subjectivity” (Nussbaum 257). Her theory is derived from a line of philosophical thinking descended from Immanuel Kant, and thereafter Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin. Although the theory most espoused by Kant [2]/MacKinnon/Dworkin understands objectification as necessarily negative, Nussbaum does not: “objectification may be a joyous part of sexual life—and maybe this sort of mythic focusing on body parts is even a regular or necessary feature of it.” These implications of the potential ‘positive’ opportunities for objectification aside, [3] Nussbaum states that the consideration of specific body parts as objects of their own is a critical aspect of objectification. This feature of Nussbaum’s theory of objectification proves why Venus pudica is a stark example of early objectification of the female body: because the Venus pudica is her concealed pubis.

Venus pudica is the pose of modesty; as Salomon writes in chapter five of Generations and Geographies, “pudica is etymologically related to pudenda,” meaning both shame and genitalia (Salomon 74). The Knidia is literally “defined by her pubis.” The mythological story behind the statue goes that Aphrodite stood undressed as she stepped from her bath and heard someone approaching. The goddess’ reach to conceal herself dominates the viewer’s impression of Aphrodite, creating a “sexual narrative of protective fear.” In one of her most prophetic passages, Salomon writes,

The hand that points also covers and that which

covers also points. We are, in either case, directed to

her pubis, which we are not permitted to see.

Woman, thus fashioned, is reduced to her sexuality…

(Salomon 73)

Salomon’s account is highly compatible with the theory of objectification articulated by Nussbaum. Mapping Nussbaum’s terms onto traditional depictions of the Venus pudica proves easy. The Knidian Aphrodite, in a “perpetual state of vulnerability,” is infinitely inert, powerless, violable. Her many subsequent iterations, whether in Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1485-1486) or Manet’s Olympia (1863), make her also infinitely fungible—exchangeable, replicable. Most importantly, we remember that Nussbaum stipulates that focusing on specific body parts is an essential aspect of objectification. By making the pubic area the focal point of the pose, Venus is reduced to her anatomy. In the eye of the beholder, the fearful stance of Venus’ exposed body conflates vulnerability and desirability, rolling these traits all into one confusing package of womanhood and sexual meekness. The Venus pudica has been thus represented over and over as such in the Western art canon for hundreds of years… until the age of the smartphone. [4]

3. KYLIE JENNER AND THE MODERN IDEAL WOMAN

If Venus pudica represents the classical ideal woman, who represents the modern ideal woman? And how did a history of the objectification of women become a narrative of self-objectification on social media? I propose answers to these questions by examining the case study of Kylie Jenner.

Author Jia Tolentino writes in Trick Mirror: “Today’s ideal woman looks like an Instagram—which is to say, an ordinary woman reproducing the lessons of the market-place… [she] coexists easily with feminism in its current market friendly and mainstream form” (Tolentino 63-65). Jenner, the paradigmatic Instagram presence, is the perfect subject for an analysis of this new woman. According to a quick Wikipedia search, Kylie Jenner is the fifth most-followed person on Instagram in the world with 170 mil-lion followers. She even leads her sister Kim Kardashian West, who has 166 million followers. Her profile (@kyliejenner) features moments from an inconceivably luxurious life: photoshoots for magazines, trips to Turks and Caicos, glittering purses used for one red carpet.

On April 7th, 2020, Forbes announced that Kylie Jenner is “still the youngest self-made billionaire in the world” (Peterson-Withorn). Jenner achieved this title in March of 2019 when she sold 51% of her successful makeup retail brand, Kylie Cosmetics, to the beauty company Coty Inc. for a reported sum of $600 million. There have been many merited criticisms of how self-actualized Kylie Jenner actually is, already having access to the resources and platform of an uber-famous family. Nevertheless, Jenner (at least superficially) represents an epitome of individual financial success. Described in a recent Vox article as “a nymph born when Zeus threw a track of hair extensions into a boiling ocean” (Abad-Santos), Jenner represents aesthetic and material success of nearly inconceivable magnitude.

This, then, is the modern ideal woman: financially independent, successful, beautiful, seemingly flawless. She has harnessed the individualistic spirit of mainstream feminism to become whatever she wants to be and look gorgeous while doing it. Unlike the passively and unwillingly admired Venus pudica, the modern ideal woman assures herself that she’s the architect of her own admiration—like Jenner, who defines exactly how she is to be desired by her millions of fans and consumers.

Kylie Jenner has actually replicated the Venus pudica pose in several of her own Instagram posts. [5] The most recent one was posted on March 4, 2020. In the photo, Jenner stands on a whitewashed staircase next to Anastasia Karanikolaou (@stassiebaby). A palm tree sways in the background, giving the impression that the photo was taken on a beach vacation. So does Jenner’s outfit; both women are wearing sheer, form-fitting neon mesh dresses reminiscent of bathing suit cover-ups. The dress is slung loosely around the shoulders and is highly impractical for actual wearing—it would just slide off. This stretchy, clingy fabric seems to have been made for the sole purpose of being worn in a photo that would highlight Kylie’s curves. [6] More to the point: underneath the dress, Kylie appears utterly naked. The sheerness of the fabric has the same function as the original pudica gesture: it suggests and emphasizes Jenner’s nakedness so that it becomes the overt focus of the picture.

Unlike the Knidian Aphrodite, who averts her gaze in an attempt to modestly conceal herself, Jenner stares directly up at the camera. Her gaze is pouty, sensual. Her hair is dyed, her nails and toes perfectly manicured to match the pink slip dress. She’s confident and emanates a glow of wealth, youthful beauty, power. This is what the ideal modern woman looks like. No longer “inert” or “violable,” she is independent and self-powerful, aware and in charge of her beauty. Unlike the Knidian Aphrodite, caught in a moment of vulnerable, shameful indecency, Kylie chooses to show off her body on her own terms, and ultimately, for her own financial benefit.

This March 4 post does not, however, pretend to be a natural photo. It’s clearly a staged picture taken for the purposes of seeming luxurious and beautiful. In fact, Kylie Jenner’s entire brand is a case against natural beauty. Her makeup company, Kylie Cosmetics, is founded on the very belief that one can improve their appearance with lipstick and foundation. In the past, she’s advertised beauty products like hair-growth gummies and weight loss detox teas. [7] Kylie herself is a testament to the tools of modern beauty. Many sensational articles scattered across the Internet debate whether Jenner has had plastic surgery by comparing then-and-now photos of a younger iteration of Kylie (a previous version who’s considerably paler and less expertly assembled… and also probably thirteen years old). The current Kylie, at 22, is knit together by fillers, hair and eyelash extensions, spray tan, and chattering acrylic nails.

Jia Tolentino has a name for this phenomenon: optimization. According to Tolentino, “the ideal woman” is “always optimizing,” eagerly taking up tools of beautification and self-improvement that the market provides her to become the best, most appealing version of herself she can possibly be (Tolentino 64).

Optimization and self-objectification are close cousins connected by a particular behavior: self-surveillance. A 2019 peer-reviewed article by Butkowski, Dixon, and Weeks defines self-objectification as the tendency “to adopt an externalized or outsider view of their own bodies,” the “behavioral manifestation” of which is called “body surveillance, or a preoccupation with monitoring one’s physical appearance and attractiveness” (Butkowski et al. 386). Self-surveillance is a necessary aspect of self-objectification; it’s behavior which allows an individual to perceive themselves as an other, to zero in on their body in a targeted and distant way. This description of self-objectification aligns closely with Nussbaum’s theory of objectification, which includes focusing on specific body parts. In Trick Mirror, Jia Tolentino describes how athleisure, the “uniform” of optimization, “eroticizes capital” and “frames the female body as a financial asset: an object that requires an initial investment and is divisible into smaller assets—the breasts, the abs, the butt” (Tolentino 88). In a capitalist society that values efficiency and progress, optimization quickly becomes entangled in a distanced and objectified view of the self. Athletic wear, makeup, and all sorts of beauty products tackle physical self-improvement as everyone knows you should tackle any project: one step at a time. Exfoliating scrubs smooth your skin, squats tone your butt, injections make your lips more kissable. A woman should undertake these smaller projects and focus carefully on all of her smaller “assets” so that eventually, she can post a picture on Instagram displaying her total physical perfection. In other words, the modern ideal woman must engage in self-surveillance, therefore objectifying herself, to become ideal.

The kicker of optimization is its cloakedness. The whole premise of optimization that the end result is supposed to imitate a heightened reality of beauty or streamlined lifestyle, an “inorganic thing engineered to look natural.” Tolentino writes,

the work formerly carried out by makeup has been

embedded directly into her face; her cheekbones or

lips have been plumped up … The same is true of

her body, which no longer requires the traditional

enhancements of clothing or strategic underwear; it

has been pre-shaped by exercise that ensures there

is little to conceal or re-arrange. (Tolentino 64)

While she denies plastic surgery, since 2015 Jenner has admitted to getting lip fillers to achieve the full, pouting lips for which she is famous. Consumers of Kylie’s lip products know of Jenner’s procedures and that lip gloss alone won’t replicate the enviable plumpness of her lips. People buying Kylie lip kits aren’t buying them in spite of her unnatural lips, but because of them. There is a strange doublethink here: Jenner admits that her full lips aren’t natural, but they’ve become such an essential part of her brand that we think of them almost as natural. The lips are artificial. The lips are Kylie. Thus, the enviable artificial gets accepted as natural.

This new standard of natural, then, allows the ideal woman to accept optimization as normal. The over-whelming “stratum of expensive juices” and “boutique exercise classes” quiet to an undetected hum beneath her blissfully independent and totally self-actualized life. Tolentino writes, damningly, that it is now “psychologically seamless … for an ordinary woman to spend her life walking toward the idealized mirage of her own self-image” (65).

Above all, what’s most dangerous about the recursive processes of self-surveillance, self-objectification, and optimization is that we’ve made it a moral pat-on-the-back. The conflation of beauty with innate moral virtue is a part of Western philosophy that traces back to Socrates. Plato’s account of Socratic dialogues in the Republic show that classical philosophy has always linked beauty and personal virtue. In the Republic, Socrates says one can hone their appreciation of The Good by cultivating “passion for beauty” and an appreciation of the Beautiful through musical training and also through physical training. Socrates says in the Republic,

I … do not believe that a healthy body, by means

of its own virtue, makes the soul good. On the contrary,

I believe that the opposite is true: a good soul,

by means of its own virtue, makes the body as good

as possible. (Plato 86)

Socrates does admit that just slapping on lipstick or having a muscular body doesn’t make the soul good. Yet what he does imply is that a healthy body is a reflection of a good soul—a temperate, strong, contemplative person. This connection between physical perfection and innate virtue is a dangerous one. It implies that personal goodness is reflected in external appearance. This was a conclusion mirrored by Aristotle and also later by Immanuel Kant, who thought beauty was a symbol of morality (Ginsborg). The idea that physical beauty reflects innate moral value has become incarnate in Western philosophy and capitalist values. Thus, “women attribute implicit moral value to the day-to-day efforts of improving their looks, and failing to meet the beauty standard is framed ‘as a failure of the self’” (Tolentino 79). With the blurring of artificial and natural beauty, everything becomes even more confusing. Our internalized conflation of beauty with morality dangerously predisposes us to believe that beauty such as this is a necessity, and is our ticket to being taken seriously [8] in society, in a just republic, á la Plato.

4. THE POSTMODERN IDEAL WOMAN: AN EXAMINATION OF THE #AERIEREAL CAMPAIGN

It is the artificiality in all of this which some women have begun to take offense to. The idea that beauty is one specific body type achieved with CrossFit and lip fillers—and even more pressingly, that this body makes some individuals more valuable than others—has begun to chafe. Thus, another ideal woman was formed in objection to the idea of optimization: the postmodern ideal woman. If modernism is an artistic philosophy “based on idealism and a utopian vision of human life and society and a belief in progress,” postmodernism is a skeptical reaction to this mindset. Postmodernism “challenge[s] the notion that there are universal certainties or truths” and emphasizes that “individual experience … [is] more concrete than abstract principles” (“Postmodernism”). The postmodern ideal woman rejects the premise represented by the likes of Kylie Jenner which promotes artificial beauty as a way to communicate self-actualization and self-worth. Instead, the postmodern ideal emphasizes an expanded definition of beauty, scorns artificiality, and embraces women’s individualism. For the purposes of this argument, I will examine the brand Aerie as a proponent of the messages I’ve described.

In 2014, lingerie brand Aerie (a branch of American Eagle Outfitters) launched a new campaign called AerieREAL in which they vowed to never use any retouched photos of models. Aerie’s stated goal is to make their brand more inclusive by featuring models of different body types and more models of color. Along with their slogan “Power. Positivity. No retouching,” [9] their ads feature lovely, smiling, makeup-free women with the sunlight just catching their faint stretch marks. The driving mission behind Aerie’s brand is that anybody can look naturally beautiful in their lingerie and apparel, that a person of any shape or color can wear their clothes.

As a part of the AerieREAL campaign, Aerie also began the #AerieREAL Role Model program to feature individual women in the public eye championing body positivity and doing other cool, famous things. The 2020 roster of #AerieREAL Role Models includes women of different races, backgrounds, body types, sexualities, abilities, and experiences; featuring Tiff McFierce (the first female DJ for the New York Knicks), Aly Raisman (Olympic gold medalist and sexual assault advocate), sustainability activist Manuela Barón, actresses Beanie Feldstein and Lana Condor, and Tony Award winner Ali Stroker among several others. This aspect of the campaign is to celebrate individual successes, something Tolentino discusses as a cornerstone of mainstream feminism.

Aerie still operates in a consumerist society. The commercial success of the brand is directly tied to how much importance we place on commodities and the things we buy to act as a form of self-expression. By choosing where and how we spend our money, we reveal our principles and tastes. So for consumers wanting to put their moral compass where their money is, female empowerment, individuality, and authenticity are music to the ears. Aerie has seen huge commercial success since the launch of the #AerieREAL campaign. CNBC reported in 2018 that Aerie’s sales “increased 38 percent in the first quarter of 2018,” and estimated that “the brand will be worth $1 billion in the next few years” (Ell). Meanwhile, Aerie’s commercial rise comes at the direct expense of the other top lingerie brand targeting young women, Victoria’s Secret. Victoria’s Secret has been criticized as being a brand catering largely to the male gaze. A 2018 article by Business Insider accused Victoria’s Secret of “failing to appeal to customers with its racy ad campaigns” which “negatively impact its teen-centric brand, Pink” (Hanbury). Compared with Aerie’s 38% growth at the same time, Victoria’s Secret “reported a 1% increase in same-store sales growth for the first quarter of 2018, following negative growth in the previous quarter” [10] (Hanbury). Many women are actively choosing to shop at Aerie over Victoria’s Secret because the experience of shopping at the latter is hyper-sexualized and gaudy, while shopping at Aerie feels like a high five from the girl-power fairy. [11]

Several studies have been done to try to examine the effectiveness of Aerie’s empowerment messaging, including a 2019 study called “Getting Real about body image: A qualitative investigation of the usefulness of the Aerie Real campaign.” This study surveyed undergraduate women from universities across the United States who were interviewed about photographs from Aerie ad campaigns, with “the majority of participants indicat[ing] improved body image (n = 23).” Additionally, “the vast majority (n = 29) of responses related to brand perceptions were extremely positive, highlighting how this campaign had maintained or increased positive perceptions of Aerie,” with many participants saying that they’d prefer to buy lingerie or apparel from Aerie because they “think more highly of the company” (Rogers et al. 129).

However, participants in the Rogers study also expressed frustrations with these images. The article states that “despite these overall positive evaluations of the Aerie Real images in terms of their departure from thin-ideal imagery and representation of greater body diversity, participants (n = 14) ... describ[ed] how the women portrayed still represented a limited range of bodies and depicted women who were conventionally attractive,” commenting that the models were “fairly small and attractive people” and, especially speaking of models of color, “still on the spectrum of lighter skin” (Rogers et al. 129).

This criticism speaks to an important truth about Aerie and other mainstream postmodern beauty ideals: they don’t go far enough. Aerie’s version of authenticity falls short because it espouses an incremental expansion of inclusivity instead of a radical overhaul of beauty standards and commercialism. The Aerie brand is still prey to the media and consumer norms it has claimed to disown: a worship of beauty, the distortion of ‘natural’, exclusive representation for models, and the objectification of women as actionless consumers. It has tried to be natural, inclusive, and individual, but it is not fully any of these things. Although many of the models have body types that would still not have been represented even ten years ago, Aerie does not feature models with the most marginalized bodies—in terms of size, color, ability, and more. [12]

Most of all, Aerie still caters to the fundamental premise that beauty is essential. As a lingerie and clothing brand, Aerie upholds the idea that a woman’s body is her most valuable mechanism for visibility, a key to participation in society. The implications of this brand prove that for women in a consumer culture, voice remains inextricable from objectification.

I will now move into a critique of the postmodern ideal that has yet to escape mechanisms of self-objectification and is still too limited in its scope of inclusivity. For the purposes of this critique, I will closely examine the fluid viewer-creator-consumer relationship and one of its symptoms, the thirst trap.

5. CRITIQUING THE POSTMODERN IDEAL: THIRST TRAPS, SELF-SURVEILLANCE, AND BEAUTY VIRTUE

On February 18th, 2019, Iskra Lawrence posted a photo of herself in a bikini. Being the face of the Aerie brand, this isn’t unusual for her. Iskra posts lots of photos of herself wearing Aerie swimsuits, lingerie, and comfortwear on her Instagram, with captions like “All my skin in all its unretouched glory” and “#celluLIT.” The February post is different, however, because it’s not a photo promoting her brand or embracing body positivity. It’s a thirst trap—a virtue thirst trap.

A thirst trap is a photo posted on social media to attract attention (positive attention, sexual attention, or just attention in general). Thirst traps are especially common among celebrities or individuals with heightened social media visibility. The concept of posting a thirst trap is deeply rooted in the objectification to self-objectification trajectory we’ve tracked as a thirst trap is an act of individual agency. To return briefly to our discussion of Venus pudica: Praxiteles’ Venus is observed by the viewer in an eternal moment of vulnerability. In Generations and Geographies in the Visual arts, Salomon writes that Praxiteles “created a goddess vulnerable in exhibition, whose primary definition is as one who does not want to be seen. In fact, being seen is here undeniably connected with being violated. Praxiteles … has transformed the viewer into a voyeur, a veritable Peeping Tom. We yearn to see that which is withheld” (Salomon 74).

The language of voyeurism is crucial to a discussion of objectification and self-objectification with thirst traps. There is an important shift in agency here. The person is promoting a picture of themselves because they want their body to be seen, unlike the Venus pudica. In this way, there is a strange fluidity between the viewer and the viewed. In her essay, “‘I Click and Post and Breathe, Waiting for Others to See What I See,’” Minh-Ha T. Pham wrote about the disruption of the one-way gaze, writing that “individuals who are the objects of the gaze are also co-creators of the interpretative conditions through which media images of their bodies and selves are seen” (Pham 225). The thirst-trap is necessarily self-aware, as the individual sees themselves also from the perspective of the other and creates the “condition” of viewership—positive attention. In the case of a thirst trap, the image is designed to elicit a specific reaction from the viewers: lust, admiration, maybe an Instagram follow.

Like Kylie Jenner, part of Iskra Lawrence’s personal brand is the display and celebration of her body. Unlike Jenner, activism is a central part of Lawrence’s social media presence. Lawrence is a spokesperson for NEDA, the National Eating Disorder Association, and she often speaks about her experiences with pressure to lose weight from the fashion and modeling industries. Interestingly, Lawrence uses her body as a platform to discuss issues that are important to her.

In her post from February 2019, Iskra wears a blue bikini that accentuates her tan. She’s gazing into the distance; a swaying palm tree is visible behind her. This is a thirst trap, but one for the purpose of political activism. Lawrence posted this picture to draw attention just so she could highlight the previous post she’d made promoting a topical art installation about male suicide. Lawrence wrote in her caption of the bikini shot: “I could post endless pictures like this but my last post is why social media is important. You may not have seen it because it wasn’t a ‘poppin’ pic, no bikini, no smile or a pretty background.” This thirst trap is quite literally a trap for viewers. Fully aware that posts showing more of her body garner more likes and views, Lawrence used this picture as bait to direct people instead to her last post “rais[ing] awareness of the male suicide epidemic.”

Lawrence engages here in a practice Tolentino refers to as “virtue signaling” in her essay “The I in the Internet.” Tolentino writes “a righteous political post on Twitter has come to seem, for many people, like a political good in itself” (8). These repostings are meant to reflect one’s own political righteousness and even label oneself as good. In this way, Lawrence’s virtuous thirst trap can be described well by a study by Mendelson and Papacharissi referenced in Pham’s article which concludes, “while narcissistic behavior may be structured around the self, it is not motivated by selfish desire, but by a desire to better connect the self to society” (Pham). Iskra Lawrence’s post was intended to highlight her beauty but as a means of connecting herself to larger social issues, even shaming the viewer slightly for being attracted to a pretty image instead of the real issues at stake.

Lawrence’s post raises important questions about using the female body as a political platform, questions that have everything to do with self-objectification. In other words, promoting her political opinion (and tangentially highlighting her own virtuousness) could only be achieved by posting a bikini pic. Hyper-aware of the attention that her visible body attracts, Iskra was trying to reach the widest possible audience and bring “reality” to Instagram by reposting a political issue. In doing so, she actually distances herself from reality by using her own image as a means to an end, a springboard for self-righteousness. Ultimately, Lawrence’s post reveals the confusing truth that power, for women, is conditioned upon the body. Most of all, it reinforces the shortcomings of the postmodern ideal: that the postmodern ideal is not willing to budge on the importance of beauty or sever the ties between beauty and moral value.

6. CONCLUSION

The difficult connection between beauty and morality is at the heart of matters regarding women’s objectification and self-objectification. How can we truly celebrate individualism or women’s achievement if their voice is always conditioned upon the body? Women have gained agency in their ability to represent themselves on social media, but their self-determined media presence still has everything to do with the physical self.

The postmodern ideal woman does have real and profound importance, especially with regard to pushing the envelope when it comes to women of color and women with non-normative bodies. It is important for women to be able to represent themselves, and not all forms of representation incur self-objectification. For example, Minh-Ha T. Pham’s “‘I Click and Post and Breathe’” article tracks the importance of selfies as a way for women of color and women with marginalized bodies to claim space on the Internet. It is essential for women to have agency with respect to the creation and publication of their own image.

It’s also essential to expand the definition of what beautiful means to include all women. Aerie, as a mainstream brand and early proponent of body acceptance and representation, still has made important contributions to the authentic representation of women. Nevertheless, the criticisms voiced in the Rogers study—that Aerie models are still conventionally beautiful, have lighter skin tones, and are still relatively thin—are all true. For instance, Aerie does not represent women of color like another brand does, Savage X Fenty: a relatively new lingerie brand by Rihanna. Savage X Fenty campaigns feature a majority of women of color in their ads and are far more representative of a range of bodies. The “Savage X in the Press” webpage features the following press quote: “Rihanna organically injects representation into her shows. It doesn’t seem like forced diversity and inclusion or some business KPI to check off a list. She is just doing the work to ensure that everyone can see a bit of themselves in her collections.” Whereas Aerie’s ad campaigns often feel forced and self-congratulatory, Rihanna isn’t trying to demonstrate her own virtuousness for representing women more authentically; she just “does the work.” Although the brand’s purpose is to celebrate women and escape exclusive representation, Aerie still defines itself in terms of white feminist, cisgender, thin-ideal norms.

Yet ultimately, all of these brands and ‘postmodern’ beauty standards fail to face the ultimate problem of making beauty simply less important. As Jia Tolentino summarizes in “Always Be Optimizing”:

A more expansive idea of beauty is a good thing—I have appreciated it personally—and yet it depends on the precept … that beauty itself is still of paramount importance. The default assumption is that it is politically important to designate everyone as beautiful, to make sure everyone can [feel beautiful]. We have hardly tried to imagine what it might look like if our culture could do the opposite—de-escalate the situation, make beauty matter less. (Tolentino 80)

This might seem like a bit of an existential cop-out to wonder “Why does this even matter at all?” Yet I think that the exercise of questioning the importance we place on beauty as a mechanism for achieving respect and moral virtue is a valuable one. We must continue to wonder why, with all the agency women continue to gain, we must still be beautiful in order to be good.

Works Cited

Abad-Santos, Alex. “The Controversy over ‘Kylie Jenner, Self-Made Billionaire,’ Explained.” Vox, 15 July 2018. Web.

Butkowski, Chelsea P., et al. “Body Surveillance on Instagram: Examining the Role of Selfie Feedback Investment in Young Adult Women’s Body Image Concerns.” Sex Roles, vol. 81, no. 5/6, Sept. 2019, pp. 385–397.

Peterson-Withorn, Chase. “Kylie Jenner is Still the Youngest Self-Made Billionaire in the World.” Forbes, 7 Apr. 2020. Web.

Ell, Kellie. “Aerie Rapidly Gaining Market Share off Social Media and ‘More Authentic’ Women.” CNBC, 23 June 2018. Web.

Ginsborg, Hannah. “Kant’s Aesthetics and Teleology.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2019. Web.

Hanbury, Mary. “These Photos Reveal Why Women Are Abandoning Victoria’s Secret for American Eagle’s Aerie Underwear Brand.” Business Insider, 20 Jul. 2018. Web.

Johnson, Robert, and Adam Cureton. “Kant’s Moral Philosophy.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, Spring 2019. Web.

Low, Elaine. “Why the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show Was Canceled.” Variety, 22 Nov. 2019. Web.

Nussbaum, Martha C. “Objectification.” Philosophy & Public Affairs, vol. 24, no. 4, 1995, pp. 249–291.

Papadaki, Lina. “What is Objectification?” Journal of Moral Philosophy, vol.7, no. 1, Apr. 2010, pp.16-36.

Pham, Minh-Ha T. “‘I Click and Post and Breathe, Waiting for Others to See What I See’: On #FeministSelfies, Outfit Photos, and Networked Vanity.” Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, vol. 19, no. 2, Apr. 2015, pp. 221–241.

Plato. Republic. Hackett, 2004.

“Postmodernism.” Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms. Web.

Rodgers, Rachel F., Lou Kruger, Alice S. Lowy, Stephanie Long, Chloe Richard. “Getting Real about Body Image: A Qualitative Investigation of the Usefulness of the Aerie Real Campaign.” Body Image, vol. 30, Sept. 2019, pp. 127–134.

Salomon, Nanette. “The Venus Pudica: Uncovering Art History’s ‘hidden Agendas’ and Pernicious Pedigrees.” Generations & Geographies in the Visual Arts: Feminist Readings, ed. Griselda Pollock, Psychology Press, 1996, pp. 69–83.

“Savage X in the Press.” Savage X Fenty. Web.

Tolentino, Jia. Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion. Random House, 2019.