Revisualizing 1904

Saguna Raina

aug 2020

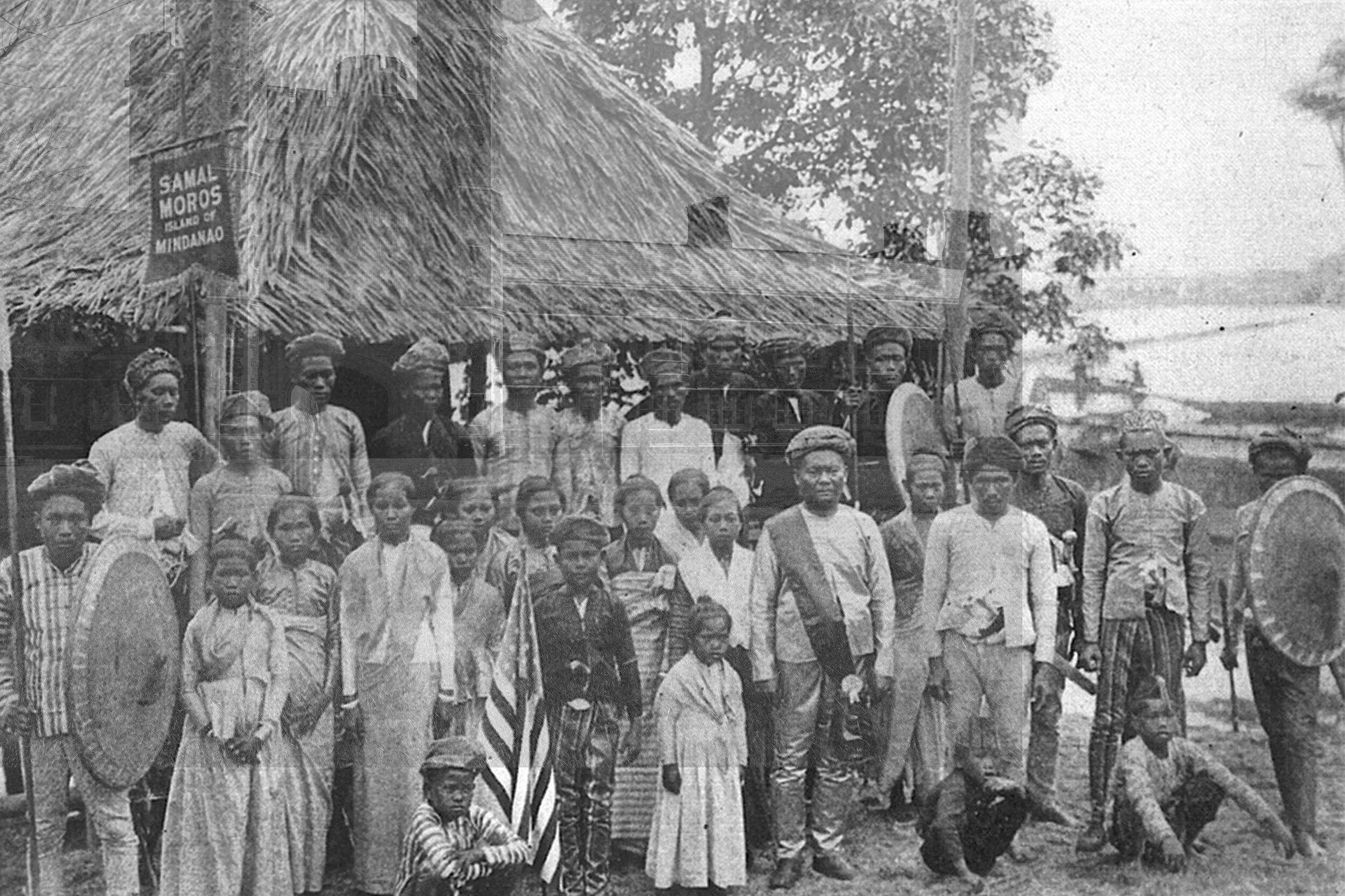

Photo by Rachel Paulk. Image from 1904 World’s Fair exhibit replicating villages on the island of Mindanao, superimposed onto modern day Washington University campus.

I think one of the very first things I remember seeing on WashU’s campus was the iconic Olympic rings that sit outside of Francis Field. There is this incredibly awkward photo of me during a campus tour, standing in front of the rings, smiling with a WashU map and drawstring bag in hand. It was a fleeting moment, and I never really gave much attention to the rings after that. The 1904 Olympics did not seem like an enthralling topic, and so I did not indulge further into any sort of conversation related to it. About a month into my second semester of my freshman year, my American culture studies professor assigned a project on the 1904 World’s Fair. For my project, my partner and I ended up researching the racial violence that occurred just across the street in Forest Park, and on the east end of campus. The final product of our project was a set of photos, with images of the human zoo exhibits superimposed onto a modern day WashU campus. Our goal was to emphasize the university’s role in these events, and to reframe the 1904 World’s Fair through a contemporary lens.

Following this project, I decided to revisit the nine by sixteen Olympic rings statue that I had blatantly ignored for a majority of my freshman year. From my World’s Fair project and from my first-year seminar in Monumental Anti-Racism, I had found research on multiple forms of racial violence that had also occurred at the Olympic games. For whatever reason, I had hopes of finding some sort of recognition of this when I went to go look at the rings statue. But instead, I only found an engraving that states, “The Olympic Stadium at Washington University was the site of the first Olympic games in America. Known as the games of the III Olympiad, the St. Louis Olympics in 1904 introduced the practice of awarding gold, silver, and bronze medals for first, second, and third place. The medal podium design of this sculpture honors this enduring legacy.” Disappointed by the lack of acknowledgement of the prejudiced nature of the games, I decided to turn to the internet to find more information on the statue itself. The following results that came up were mainly from The Source, WashU’s news and publication site. According to a couple of different articles, the rings were unveiled on September 28, 2018, and there were various ceremonies held to honor the event. Several representatives from the St. Louis Sports Committee, WashU alumni, and current student athletes were present at the event (McCarthy). Following the unveiling, there were bursts of fireworks and sparklers, further playing into the grandeur of the entire experience. The reactions were overall positive, and there were seemingly no debates about the significance of this sculpture and its possible effects on campus life. On September 28, 2018, editor Natalie Geismar released an op-ed in Student Life, WashU’s independent student-run newspaper, calling attention to the racist nature of the 1904 Olympics. Two days later, editor Lauren Alley published an article with similar sentiments. Alley described the games as a “disgusting show of racism,” and cites the Anthropology Days as an example of this. The Anthropology Days was a crossover between the Olympics and World’s Fair, where natives were taken from the human zoo exhibits to participate in an experiment related to athletic ability. Anthropologists who were overseeing the event hoped to emphasize the differences between “primitive man” and “modern man” by comparing native African, Fillippino, Patagonian, Japanese, Mexican, and Sioux Native American men to caucasian men. In the end, it was concluded that the results indicated racial inferiority, and that uncivilized adults could be compared to “civilized” children (Brownell).

Photo by Rachel Paulk. Image from 1904 World's Fair exhibit replicating an Arapaho village, superimposed onto modern day Washington University campus.

Geismar states in her article that the rings “serve as a permanent, tangible reminder of St. Louis’ and Washington University’s deeply racist past,” specifically in regards to the 1904 Olympics and World’s Fair. The reality, however, is that the rings do not actually remind anybody of the university’s racist history. Other than these two student-produced articles, there are no saved or published statements of dissent in regards to the rings statue, nor is there any record of a conversation about the racist implications brought on by this statue. During the rings’ opening ceremonies, Chancellor Mark Wrighton stated that “We may not be exactly the university we are today without this kickstart from the fair and Olympics” (McCarthy). This statement suggests that the rings are being celebrated for what the Olympics have evolved into, a well-respected international set of competitions for the elite, rather than for the values and principles that they were founded on.

Michael Rothberg explains in his book, The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators, that people or institutions “may still contribute to, inhabit, or benefit from regimes of domination that [they] neither set up nor control,” even if they are not acting as direct agents of harm. Although the university is not directly harming anyone by celebrating the Olympics, in overlooking the prejudiced identity of the games, WashU is acting as a bystander to the racial injustices that occurred on its own campus grounds. The university’s complicity is surprising considering it claims to be a leading advocate in goals related to diversity and inclusion. On its Diversity & Inclusion homepage, the university discusses four frameworks of change—confronting bias, charting progress, planning an inclusive future, and having a campus accessible to all. The frameworks are supposedly addressed through inclusion trainings, signature initiatives, and other campus wide projects. For an institution that seemingly prides itself in its ability to address inclusion and diversity, it is extremely startling to see a lack of commemoration of the racist aspects of the Olympic games. By not acknowledging these specific moments in history, WashU is failing to confront its own biases, and therefore failing to uphold one of the university’s core values. There is no simple way to acknowledge an institution’s racist past. Admitting that the university participated in, oversaw, and encouraged certain types of prejudiced ideals may bring harm to WashU’s reputation. But by not recognizing our past, we are erasing a large part of history and therefore preserving selective memories of racial violence and injustice. The actual history behind the 1904 Olympics is currently hidden behind an extravagant statue that gives the illusion of respect, honor, and prestige. There needs to be some sort of remembrance of the university’s role in perpetuating ideas related to colonialism, exceptionalism, and racism. Ultimately this remembrance should come in the form of a visual redress, as this will help to physically disturb the narrative that the rings currently present. With the use of images, a counter monument, or perhaps a map-like interface, the university will be able to recognize its complicit role in moments of racial violence, thus providing a forum for students and faculty to engage in meaningful and necessary conversations on systemic racial issues. If WashU is going to continue to use rhetoric surrounding diversity and inclusion to promote itself, then there needs to be an initiative to make sure that these values are actually visible and present on campus.

Works Cited

Alley, Lauren, editor. “On Olympic ‘Pride’ and Bad Statues.” Student Life, 1 Oct. 2018.

Brownell, Susan. The 1904 Anthropology Days and Olympic Games: Sport, Race, and American Imperialism. U of Nebraska Press, 2008.

Geismar, Natalie, editor. “Op-ed: WU’s Olympic Rings: A ‘Spectacular’ Commemoration of Racism.” Student Life, 28 Sept. 2018.

McCarthy, Leslie Gibson. “Meet Me at the Rings.” The Source, 3 Oct. 2018.

“Olympic Rings Sculpture to Be Dedicated Sept. 28.” The Source, 26 Sept. 2018.

Rothberg, Michael. The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators. Stanford UP, 2019.