Commodifying Diversity: The Danger of Racial Capitalism on Student Growth in Higher Education

Jewel Evans

aug 2020

“In what ways do you contribute to our diverse student body?” This is a question I was asked countless times during the college admissions process. As a Black woman I fit into two minority groups, but do I really want to spend 350 precious words explaining only these physical aspects of my identity? I have other interests: my aspirations in the medical field, love for cooking and curiosity in monotheistic religions, which happen to intersect with both my race and gender. All the question asks, however, is what makes me “diverse” enough to be a student at X University.

Diversity has become a buzzword in higher education. It is plastered across brochures that boast about the promise of a diverse student body and talked about in admissions interviews, but while the word itself is popular among universities across the country, the practice of diversity and its effects on students are often lost in translation. Dr. Amber Musser is a professor and researcher in the area of African American, women, and sexuality studies, three categories that she personally fits into. In her piece “Specimen Days: Diversity, Labor, and the University,” Dr. Musser recounts her own experiences with diversity as a faculty member at various universities and introduces the idea that diversity is often commodified in higher education, a practice that yields more negative consequences than positive ones. For many, this concept is unfathomable—after all, isn’t diversity a good thing? Inclusivity, in a general term, is undoubtedly beneficial, but the commodification of this practice benefits predominantly all-white institutions themselves more than the wellbeing of the minority students that it targets. An informal survey conducted as part of this essay reveals that students do not always view their race or ethnicity as the most important aspect of their personality. When institutions focus solely on a student’s race or ethnicity, they overlook other interests and treat the student as a form of capital. The commodification of diversity is a selfish practice that is potentially harmful to the growth of students and serves to uphold the very stereotypes that inclusivity works to combat.

Commodification is defined as the action or process of treating something as a mere commodity. The use of the word mere is critical in understanding exactly why this process is harmful. The commodification of something reduces its value and turns it into currency. A great way to understand this concept is through the definition of racial capitalism. In her article for the Harvard Law Review, Nancy Leong, J.D., defines this term as “the process of deriving social and economic value from the racial identity of another person” (2153). Leong’s piece is important to reference when understanding how commodification of diversity harms students, such as Diallo Shabazz, a Black former student at the University of Wisconsin. Shabazz was photoshopped into a picture on the cover of the university’s admissions booklet in 2000. He told NPR that he was not made aware that his image would be used in the booklet and did not appreciate how he was being falsely marketed (Prichep). This is a perfect example of Leong’s warning: “Affiliation with nonwhite individuals thus becomes merely a useful means for white individuals and predominantly white institutions to acquire social and economic benefits while deflecting potential charges of racism and avoiding more difficult questions of racial equality” (2155). The university did not want Shabazz to comment on his college experience or give real details on some of his favorite moments on campus. Instead, they used his image as racial capital and overlooked his thoughts on the matter. Yes, diversity and inclusivity are beneficial, but when predominately white institutions only engage in diversity for optics, they avoid the real conversations that come with their engagement.

It is important to note that diversity and inclusivity in higher education was once (and in many ways still is) motivated by legal obligation. The term “diversity” entered the collegiate world after legal battles surrounding affirmative action ensued in the 1990s. In her piece entitled, “The Diversity Distraction: A Critical Comparative Analysis of Discourse in Higher Education Scholarship,” author Dr. Derria Byrd explains her research on the discussion of diversity between 2000 and 2015. Byrd found that for many, the concept of diversity is “merely a new spin on affirmative action, not a new concept but a new rhetoric” (137). Universities feel obligated to admit students representing a variety of minority groups because they know the world is watching. They know that they are being compared to other schools and, therefore, want to create a curated version of what they believe diversity to be. In many cases, if students are not being used simply for optics, they are brought in to serve a pre-selected role at the university. For example, a Latinx student might be expected to participate in a Latin American student group or a Black student might be expected to write for the university’s Black magazine. Predominately white institutions are realizing that a shift away from optics legitimizes their claim to uphold diversity. In place of photoshopping a person of color (POC) into their marketing, they want POC and other minority classes (such as gender and sexuality) to be as visible within the university as possible. Musser’s piece highlights the fact that in many cases “minority difference [is] fetishized within the university,” and she notes that in today’s economy, “minorities signal a particular investment in the project of diversity, even as representation is not equivalent to an actual epistemological shift” (3). Musser’s findings once again validate the idea that commodification of diversity serves to benefit the institution rather than students, or in this case faculty.

Musser also states that “people who represent minority difference on an intellectual and embodied level perform much of the university’s work on diversity” (4). In other words, if students and faculty on campus speak out on issues of diversity spontaneously, the university can take credit for this dialogue and increase its racial capital (4). This practice only works, however, if the minority-representing bodies that the university brings in are knowledgeable and passionate about issues of diversity that affect them. Because institutions are so focused on visibility of difference, it is often expected that those who fit into a minority group will be the face of a movement for the institution. Their interests are assumed, and they are reduced to only a physical representation of their minority group. In Musser’s case as a Black and queer woman, she is expected to participate in initiatives to support all three communities: race, sexuality, and gender. She describes feeling “pressure to perform authenticity” and being “continually expected to do work on behalf of [her] Blackness” when her true area of study is women’s sexuality (8). This is one of the most dangerous effects of diversity commodification. Connecting again to the very definition of a commodity, this practice reduces one’s identity to only their visible characteristics and often disregards the less visible aspects. Queerness is not visible, blackness is. Musser describes having to constantly make her queerness known in order to engage in a space where her interests and work are valued.

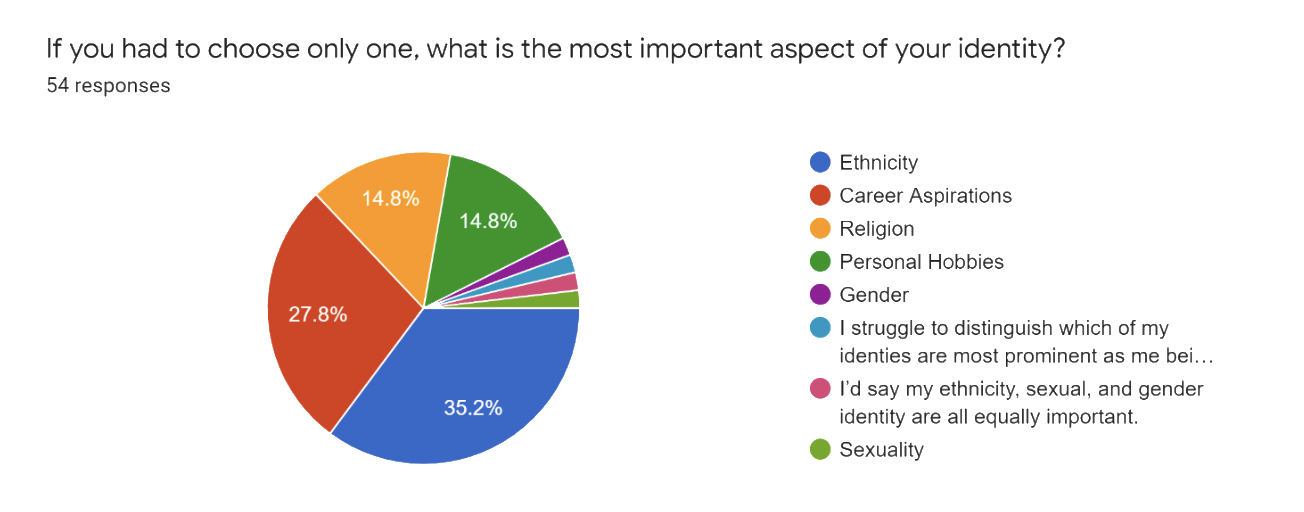

The idea that aspects of a student’s identity are overlooked in favor of only visible aspects limits the student’s personal expression and categorizes them only in a minority lens and hinders expression. I conducted an informal survey in order to better understand the connection between race and identity among undergraduate students at Washington University in St. Louis. Out of a total of 54 respondents, a little over half (53.7%) said that ethnicity was the most important aspect of their identity. Of a total of 49 respondents from ethnic minority groups, only 51% said their ethnicity was the most important aspect of their identity. When given a choice between ethnicity and other factors, only a third of respondents said that ethnicity was the most important aspect of their identity, with the majority of respondents choosing less visible academic pursuits and personal beliefs or interests over visible qualities such as race and gender.

The findings of my survey confirm the fact that assuming minority students’ interests will often lead to misinformation.

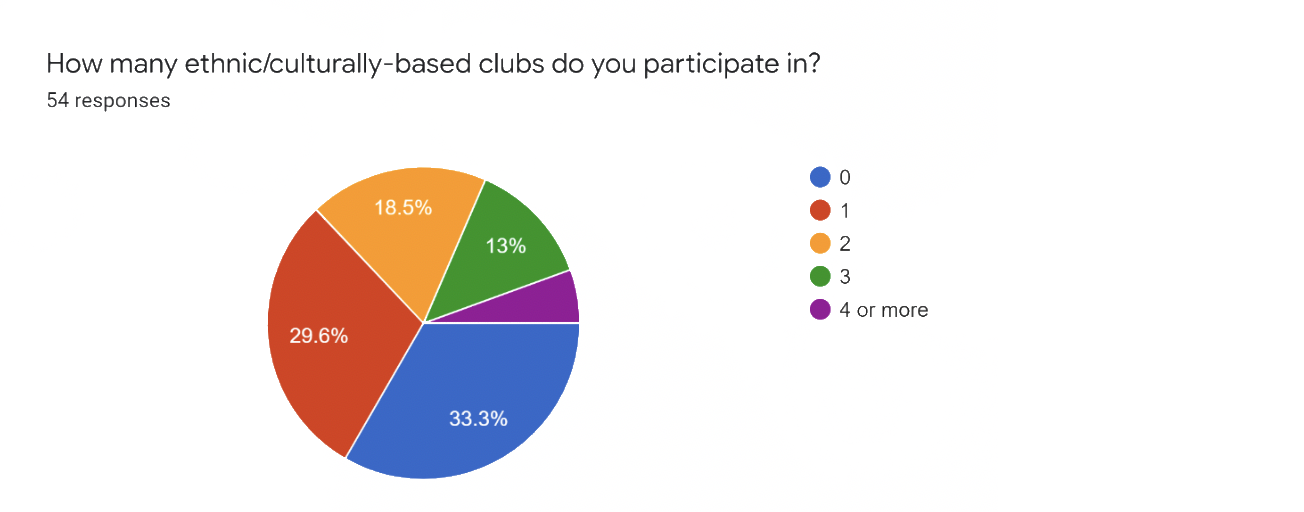

It also highlights the issue with admitting minority students with the expectation that they will represent a certain group. Respondents were asked about their involvement in student groups on campus. While almost all respondents (98.1%) participated in student groups, a third of respondents said they did not participate in culturally-based student groups. Out of 49 respondents from ethnic minority groups, over three quarters (77.5%) said that they did not participate in culturally based student groups.

This evidence further supports the claim that assuming students’ interests does not capture their true involvement. It is the job of the university to provide spaces for minority students to express themselves and engage in any capacity they choose. According to researcher Robin Cooper with the Journal of College Character, “all students need to feel they are in a campus community that supports and values them, where learning opportunities are developmental, and where they feel a strong sense of identity” (1). Cooper also finds that “[t]he feeling that they are cared about and seen as part of the campus community is tied to students’ sense of belonging; this feeling in turn is tied to student persistence” (1). Cooper’s research demonstrates how assuming a student’s interests can harm their performance if they do not feel recognized for what they truly enjoy. Expecting minority students to fit a certain role is dangerous and lazy on the part of the institution.

This practice of commodification not only limits expression but places an extra unwarranted responsibility on minorities as well. As professionals in the academic setting, both Musser and Leong can attest to this extra burden. Musser recounts her experience as a member of six different minority groups for students and faculty. Her involvement with these groups demanded that she put in “a great deal of affective labor” on top of her duties as a professor but her extra efforts were “uncompensated except for the fuzzy feeling one might get from being continually told that the ‘contribution’ one is making to the university is through the embodiment of one’s identity” (8). In her interview with Vox, Leong stated that she is expected to mentor students and attend diversity events. She suggests that, although this level of involvement is an expectation it gets treated as volunteer activity that she should be happy to do. Leong concludes that “Racial capitalism leads to a lot of extra racial work for people of color” (qtd. in Illing). Assuming one’s interests revolve around their visible identities also assumes the way they feel towards these aspects of themselves. Feeling obligated to participate in certain activities places extra work on the minority and often without compensation as this involvement is often seen as a natural part of their identity.

The college admissions process is the root of many of the largest issues with racial capitalism. Affirmative action was originally designed to stop employers and universities from discrimination for race-related reasons. This process works, however, by requiring these institutions to report data on the practices they use to combat discrimination and statistics on how many employees or students they have from minority backgrounds. If the numbers satisfy a certain set of metrics, the institution is legally within their rights. This practice makes it easy to admit a certain number of students based on a quota that the institution is expected to meet, no less and certainly no more. Dr. Qiang Fu conducted a study in Economic Inquiry that investigated the relationship between affirmative action policies and racial inequality in college admissions. Based on his results, Fu predicted that “affirmative action alone will not help reduce racial inequality in education attainment” but that universities must initiate more conscious practices for creating a truly diverse student body (427).

Apart from quota-based admission, the admissions process has the potential to engage universities in racial capitalism through student stories. This is the aforementioned prompt that haunted me so much throughout my experience: “In what ways do you contribute to our diverse student body?” What the university really wanted to know is what aspects of my identity they could use to increase their racial capital, and I knew it. As Leong points out, “it’s not like nonwhite people don’t know what’s going on here” (qtd. in Illing). Schools are looking for an interesting story. Something they can use to show their commitment to “diversity.” During his research, Fu found that many universities would add extra points within their acceptance matrix to a minority applicant only because of their ethnicity, but these points come at a cost. The reason that this question made me so frustrated is that I knew universities would value an exaggerated sob story about how my race or gender has affected me all my life and how it was my life’s mission to represent these aspects of myself to the world.

As Musser recognized in her piece, diversity is most valuable to the university if it is visible: something they can sell. Sure it can be beneficial to add extra points to an applicant’s score because of their ethnicity, but that takes away from the goal of cultivating a diverse student body which is to foster an environment of inclusion. Those that are the target of racial capitalism are aware of it, and they are often not valued because of who they are but what they are. Minority students sometimes come from backgrounds with less academic resources available to them. These students are just as capable as their more resource-rich counterparts, but they require different assets once they are admitted. Adopting a system that rewards points only based on race does not take this into account.

Racial capitalism is convenient. It gives predominantly white intuitions the opportunity to benefit from diversity but ultimately avoid the larger issues that come with it. A diverse student body is undoubtedly beneficial to the university and its students but only when done correctly and with purpose. Students should be valued for every aspect of their identity: visible and invisible. Their involvement should not be assumed—they should be encouraged to participate in any activity they feel inclined. Even within a minority setting, larger implications must be taken into consideration. If a university is willing to add points to an application because of race, they need to be ready to provide resources, support and knowledge to that student with the same eagerness.