Becoming Woman Before Becoming Human

Fears, Films, and Technologies’ Journeys to

Personhood

Joanne Sung

Sept 2023

If Frankenstein was written in the 21st century instead of the 19th, the monster created by the titular scientist may have been a deceptive, malicious, and most of all, attractive female. Or alternatively, if The Terminator was released four decades later, the Terminator may have been a ruthless, cunning, and alluring woman. In just the past few decades, we have seen a fundamental shift in the media depiction of humanized technology or HT (e.g. cyborgs, artificial intelligence, and robots) from the stoic and male—in addition to the two aforementioned examples, HAL (2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968), RoboCop (RoboCop, 1987), and Agent Smith (The Matrix, 1999)—towards feminized and sexualized robots that wield seduction rather than brute force—Number Six (Battlestar Galactica, 2003), Samantha (her, 2013), and Ava (Ex Machina, 2014).

Materially, the sex of technological beings doesn’t have any meaningful implications. In fact, one of the first examinations of cyborgs under the lens of gender theory, Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto,” argues that the potential of cyborgs to be ungendered can push us to challenge our societal hierarchies. However, in how HT actually emerged, we see that whether it be as man or as woman, there is a consistent gendering—not only in appearance and voice, but also in personality traits and mannerisms. To some extent, this gendering is central to what humanizes them, as to be human is to be constrained by human constructs.

Moreover, the shift in associated gender is especially clear when these technological beings play villainous roles. The depiction of antagonists is key as it is, firstly, the most common archetype of HT characters, and secondly, antagonists often mirror current societal fears. Many plots explore situations where humans lose control of the technology they created. However, although not as dramatized as it is in fiction, the accelerated advancements of innovations legitimize the possibility of technology changing our world irreversibly without our full awareness. Thus, in this paper, I will examine the progression of AI’s gendering under the paradigm of our evolving fears towards technology, and the ensuing implications, and analyze patterns in the top 100 grossing movies that have a robot, cyborg, or AI character.

Central to the role of media is to portray a society’s current attitudes, issues, and trends. For instance, the genre of horror is ridden with political implications when it comes to what will scare people. Even in techniques seemingly as simple as building suspense, the environmental factors that we’ve been taught to fear are the foundations of what incites terror (Tompkins), which can explain why the horror genre is historically rife with racial caricatures and stereotyping. Likewise, science fiction, thriller, and dystopian works that cast HT in some form as the antagonist can demonstrate our world’s shifting attitudes towards gender and technology.

While much of the fear around technological invention and innovation is due to a universal acknowledgment that, on an individual level, we have very little control over larger societal developments (Ehrlich and Dworzecka), a large part of this fear also stems from a mistrust of humanity itself, including the part of ourselves that could become compelled to make such creatures (Szollosy 435). More than simply the technology, we fear that we will create systems that allow for technology to gain control over humans—a dynamic that ironically reveals the fear of our own marginalizing and exploitative social constructs turning against us.

One of the earliest films centered on these fears toward technology to gain mainstream recognition was 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968). In this film, HAL, a computer with a human personality that controls the operations of a spaceship, eavesdrops on the astronauts’ conversations, takes control of the space pod and ends up killing several crewmen. Similarly, in the beginning of what would become an acclaimed franchise, The Terminator (Cameron, 1984) follows a cyborg assassin sent from the future to hunt down the film’s female protagonist. In both films, the central robotic creatures are distinctly characterized male. HAL has a monotone male voice that employs curt manners of speaking, and the Terminator is played by Arnold Schwarzenegger who is styled to embody masculinity, is devoid of emotion, and boasts an unsurpassable strength. As gendered antagonists, these HT representations associate our technological fears with distinctly male characteristics. However, the basis of our fears toward technology is constantly changing, and as new fears emerge, we have seen an interesting shift in HT characters toward femininity.

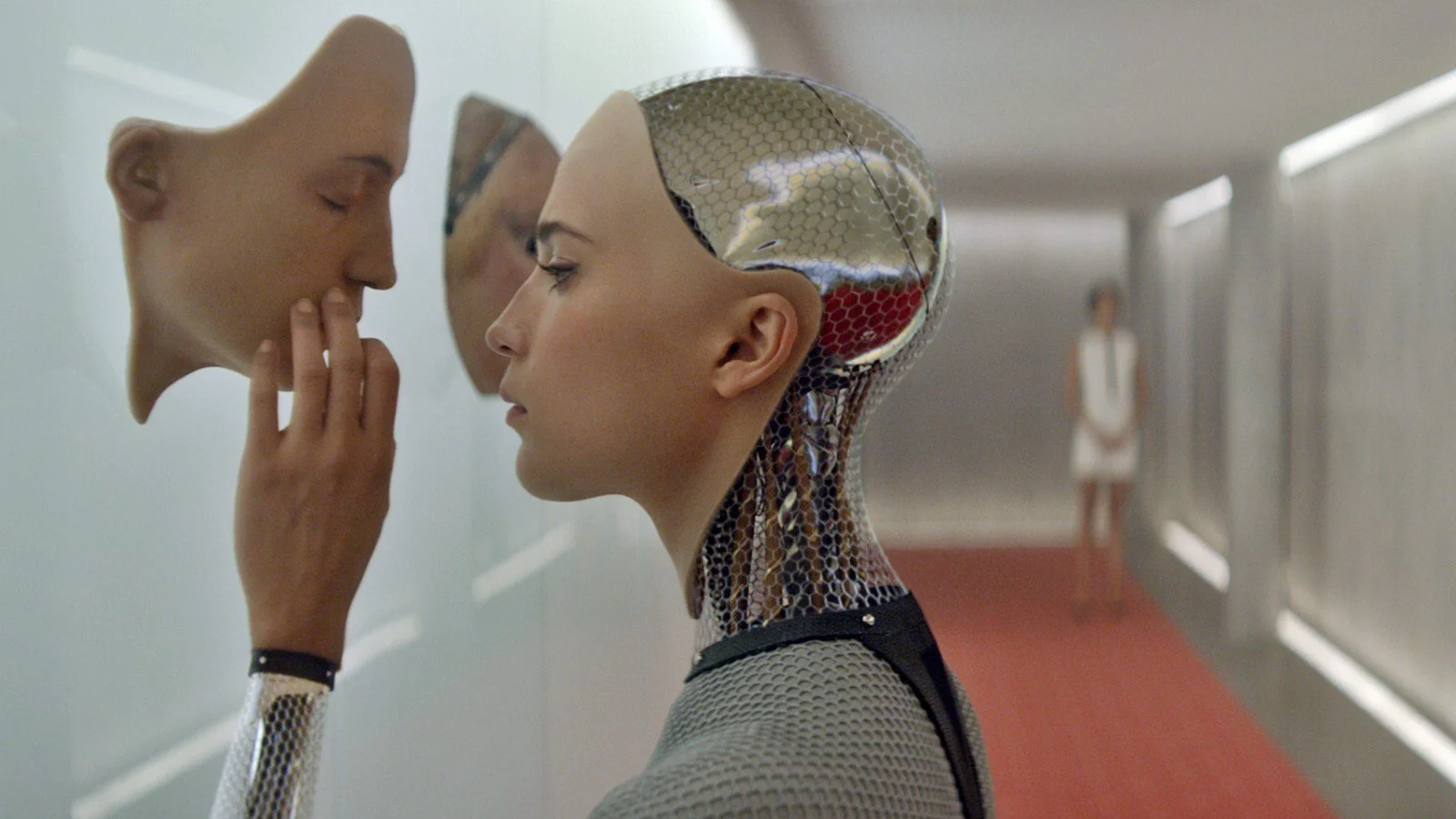

One of the first films to do this was the spy comedy Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (Roach, 1997). However, as an early representation of female-gendered HT, the film’s robots, or “fembots,” are notably limited as they do not act on their own agency—they instead operate under protagonist Austin Powers’ true nemesis, Dr. Evil—and have sex appeal as their only power. More recently, feminized HT characters have gained more complexity and more centralized antagonist roles, but they remain to be gendered via traditional social values. Two prominent, archetypal film characters display this gender-stereotyping dynamic: Ava from Ex Machina (Garland, 2018) and Samantha from her (Jones, 2013). Ava is a robot being engineered to be indistinguishable from humans, but eventually turns on her creator. However, prior to revealing her intents, Ava is consistently subservient and seductive, and her attractiveness is a central part of the film’s plot (the creator of Ava inquires multiple times to the man he brought in to test Ava on whether he is attracted to Ava as a woman). All the other robotic characters in the film are similarly portrayed—seductive but subservient robots in traditionally attractive feminine form (such as the creator’s personal servant who does not speak). In her, the portrayal of feminized HT extends beyond mere physical attractiveness and subservience. In this film, a heartbroken male protagonist falls in love with Samantha, who is nothing more than a feminized voice. While her character doesn’t appear to be malicious, fear is incited via the possibility of AI to leverage people’s emotions through the gendered attractions of personality and companionship. In addition to Samantha’s feminized voice, the character’s crucial characteristics include her naivete and gentle nature, crucially allowing her to encapsulate societal ideals for a “perfect girlfriend” and to use this role to her own advantage.

A broader picture of this trend from masculine to feminine HT antagonists can be gained from an examination of the 100 highest grossing films that have a significant character (more than 50 lines or integral to the plot) that is a robot, cyborg, or AI. Gender was determined by what was explicitly present in official movie information, such as synopses, lines on scripts, or from director testaments. If cases where none of the previous was available, characters were labeled as ungendered. Some films included additional HT characters, but if they were not significant to the plot, they were not included in the data. As seen in Figure 1, there is a marked increase of “female” HT characters in recent decades.

Figure 1. Ratios of genders of significant characters that can be categorized as 'humanized technology' in the top 100 grossing films of all time that contain one or more of a such character.

While part of this trend could be attributed to an increasing representation of women in films, the trend seems to extend far past what would be expected merely from general trends in gender breakdowns of film leads. There was an average of 16.4% female leads from 1950 to 1990 when looking at the top 50 movies for each decade, as opposed to the zero significant female HT characters in that same timeframe. Then, starting in 1990, the percentage of female HT characters consistently exceeds the general percentage of female leads, with the general percentage for the 1990’s being 8% for female leads as opposed to 25% for HT characters. The general female lead percentage in the 2000’s is 6% as opposed to 47% for HT characters, and 34% leads versus 57% female HT characters in the 2010’s (“Lead Movie Roles”). There is an undeniable trend of underrepresentation of women when it comes to lead roles, but equal representation that is approaching overrepresentation when it comes to HT characters.

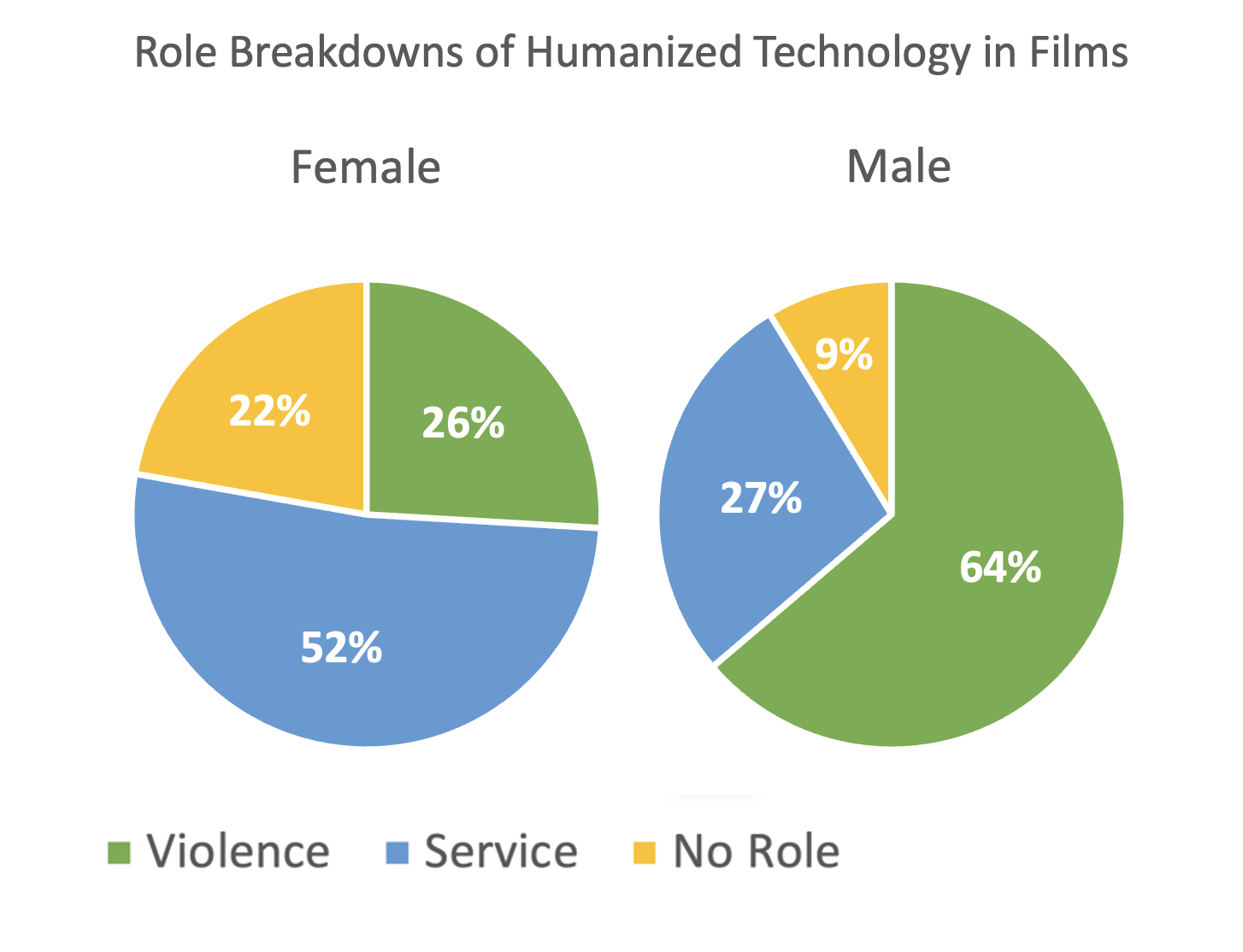

An examination of the specific role an HT character was designed for further reveals a reinforcement of gender roles (see Figure 2). In all 100 films, the HT characters could be categorized as created for violence (war, malice, taking over humanity, etc.; e.g. Optimus Prime in Transformers, 2009, Venom in Venom, 2018), service[1] (an assistant, designed to carry out a specific task, etc.; e.g. JARVIS in Iron Man, 2008, Arthur in Passengers, 2016), or not designed to carry out a role (such as a story exploring their identity; e.g. David in A.I. Artificial Intelligence, 2001). Overall, HTs gendered male are most frequently in violent roles and HTs gendered female are most frequently in service roles. Even within roles, there are additional discrepancies that reinforce gender roles. Violent male cyborgs and robots often over-rely on pure strength and problem solving. In contrast, many female cyborgs are depicted to be cunning and controlling, strengthening femininity’s association with toxicity. Also observable within the service role is the division of labor along gender lines. When not sexualized, female HT characters are given the other purpose associated with women: maternity. For example, the sci-fi film I Am Mother (Sputore, 2019) depicts a feminine robot raising a human girl. The two characters appear to share a strong emotional connection, which reinforces femininity’s association with maternal service.

Figure 2. Percentages of 'humanized technology' characters in the top 100 grossing films of all time divided by the roles intended for them at creation.

Gender is defined by binaries—we know what a man is because there is a woman to compare him to, and vice versa. Critical to this construction is the notion that man controls woman and woman serves man; from this concept comes the rest of our gender stereotypes—dominating vs. docile, competent vs. supportive, emotionless vs. generous, and the positioning of women as caregivers. As technological advances become less related to violence and power and more devoted toward creating a life without inconveniences, much of this representation of feminine HT mirrors how technology is developed to be of service, a role that then manifesting as feminine subservience as to men. In fact, three key characteristics—docility, replaceability, and artificiality—manifest in both artificial intelligence and women’s interactions with labor, intelligence, and embodiment (Sutko). This correlation between gender and technology is largely informed by our growing fears. As we seek more and more control of the technologies that should serve us, we have begun to shift the depiction of HT to the identity most easily defined by domination and subservience—a dynamic clearly evidenced by the trend of femininized HT antagonists in the films we currently create and consume.

Be it in these films, or in our perceptions overall, gendering does not work in simply a literal or physical sense—a robot is not merely a “girl” or a “boy.” Rather we associate an array of traits and actions to construct a gendered figure—we even associate certain commercial items with certain genders, such as a microwave with women or a computer with men. This form of gender construction works as a positive feedback loop—because there is already an association, household appliances get marketed to women and information technology gets marketed to men, but in that act of marketing that association becomes strengthened (Wajcman 92-96). Similarly, by trying to humanize technology, by giving it the associations and norms we are used to, we end up strengthening them. Moreover, these depictions can serve as a form of pink washing—capitalizing on our perceptions of womanhood to make technology humanized and relatable quells threats to these norms by masquerading as representation and empowerment. We must take responsibility for the stories we put out for the world to see, for when we place full faith in art always imitating life, we may miss the dangers of life imitating art. Films, stripped down, are nothing more than stories—and there are few things, even few technologies, that are more powerful than a good story.