Luxury Seating and the Art of Campus Prestige

by Priya Anand

November 2022

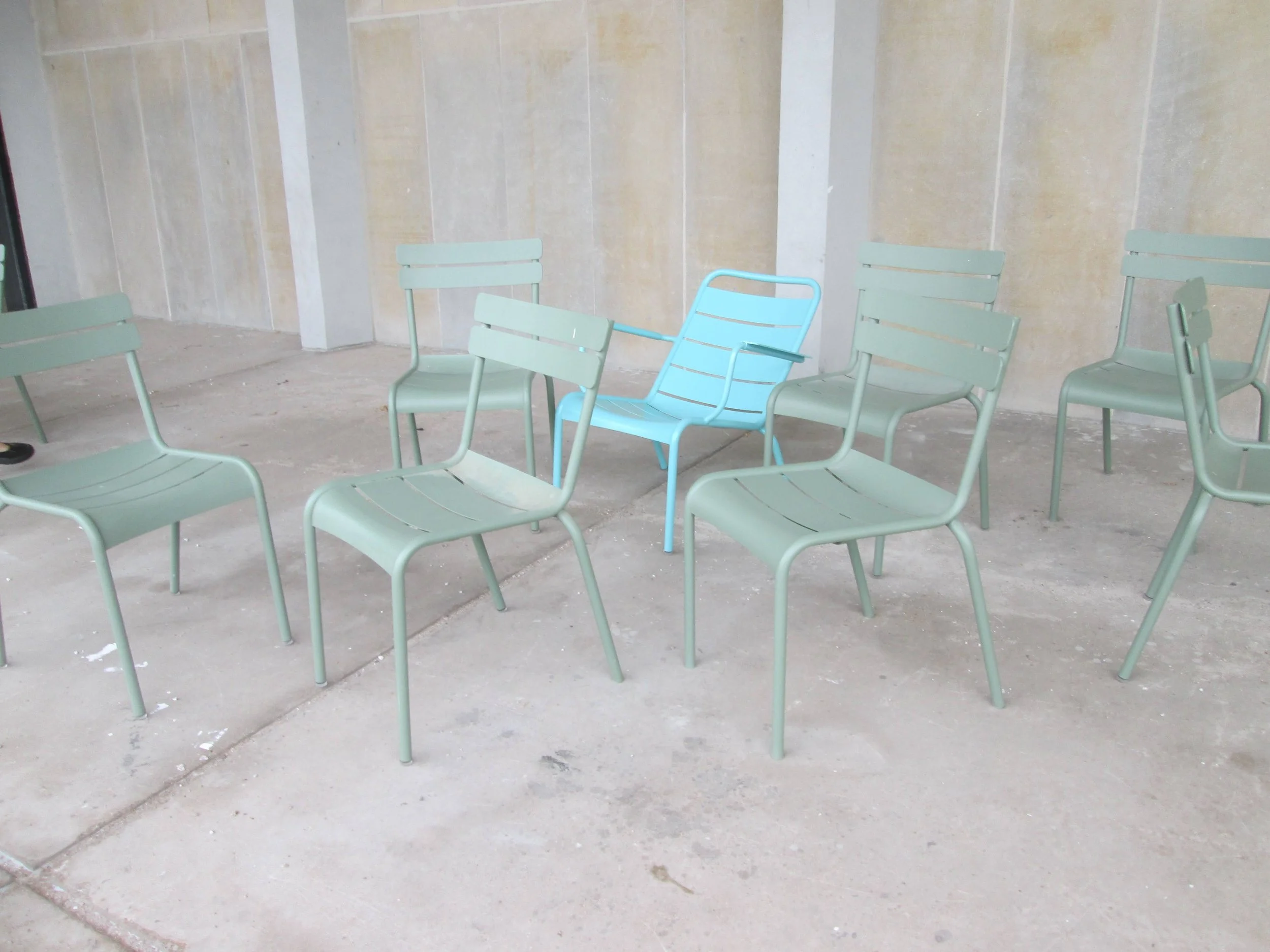

The Fermob Luxembourg Outdoor Lounge Chair, shown here and featured prominently around the Danforth campus, retails for over $1000 per chair.

In August 2022, Remake editors counted over 560 Fermob-branded chairs on the Danforth campus, many of which were Luxembourg models ranging in cost from around $450 to over $1000.

Hiding in Plain Sight

Luxury Seating and the Art of Campus Prestige

by Priya Anand

November 2022

photos by E.Bassett / J.Bassett

A key feature of the Washington University campus is the vibrant sage chairs that are scattered sporadically through the green spaces on campus. These lawn chairs became a prominent subject of discussion when students began speculating that they were Fermob’s Luxembourg chairs that cost approximately 1,000 dollars each. While some found themselves in debates, in person and on online platforms like Reddit, discussing whether such extravagant purchases were justified, others dismissed these conversations as futile speculation. A cursory glance at these chairs' logos, however, reveals that they are in fact the Fermob Luxembourg chairs. This purchase raises some questions about WashU’s spending practices and institutional priorities, but it also reveals a broader pattern of higher education institutions chasing prestige through symbolic purchases. Fermob’s Luxembourg chairs act as a symbol of prestige that allows WashU to communicate its status as an elite institution and reveals the growing commodification of higher education. By prioritizing such purchases, colleges marginalize low-income students and fail to serve the needs of their community.

The Luxembourg chairs are marketed and designed as works of art rather than practical or functional chairs. These chairs are manufactured by Fermob, a mid-size outdoor furniture company that prides itself on promoting “French art de vivre” (Harmon and Ratto). By calling their furniture “art de vivre,” which translates to art of living, Fermob suggests that it is selling an aesthetic and lifestyle, rather than just a piece of furniture. Moreover, when describing the Luxembourg collection, the Fermob website focuses on the aluminum it is made from “whose watchwords are lightness, joie de vivre and conviviality” (“Collection”). Fermob chooses to use abstract and artistic words like “lightness, joie de vivre, and conviviality” that do little to physically describe the object. By highlighting aesthetic adjectives rather than practical qualities such as build, quality of materials, or longevity, Fermob reveals that the appeal of its furniture is the design and artistry rather than its functional purpose. Additionally, this choice displays that their target audience is consumers that would value and prioritize the chair’s symbolic value as art over its practical purpose as furniture.

However, WashU suggests that they purchased these chairs primarily as a practical response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the article, “Campus Space in a COVID World,” WashU presents its key strategies to “de-densify” campus and create more spaces that allow social distancing. The very first picture the article features is one of the Fermob chairs in front of Brookings Hall (McCarthy). By emphasizing this image over their more substantial strategies, such as outdoor tents or plexiglass installations, WashU is attempting to justify this purchase as a critical piece of the university response to COVID-19. Below this photograph, the caption states, “Some 600 moveable yet durable outdoor chairs have been placed throughout the Danforth campus to give students more places to sit and socialize safely” (McCarthy). The use of pragmatic adjectives “moveable” and “durable” starkly contrasts the artistic words such as “lightness” and “joie de vivre” Fermob uses to describe the chairs. Moreover, if the sole purpose of these chairs is to “give students more places to sit,” then there were undoubtedly more “moveable yet durable” chairs that WashU could have purchased at a much lower price point. This discrepancy between the intention and audience of the Fermob chairs and WashU’s reasoning for purchasing them reveals that pandemic safety was likely not the primary motivation behind WashU’s purchase.

Instead, WashU likely invested in the Fermob chairs as a symbol of prestige. The Fermob Luxembourg chairs are distinguished from other lawn chairs by their reputation and cultural status. Firstly, the Luxembourg chairs carry prestige because of their ties to French royalty culture. The Luxembourg line was created in 2004 when Fermob asked Frédéric Sofia to reinterpret the “legendary” chairs of the Luxembourg Gardens (“Collection”). The Luxembourg Gardens and Luxembourg Palace were built under the orders of Marie de Medicis, the queen of France and wife of King Henri IV (“Luxembourg”). This connection between the Luxembourg furniture line and French elite history reveals the prestige and cultural importance of these chairs. Furthermore, these chairs were described as “an emblem of French design” and “an expression of French culture in furniture form” (“Collection”). It may seem strange for an “emblem” and “expression” of French culture to exist at multiple American college campuses with predominantly American students. However, in the essay “The Marketing of Luxury Goods,” Vickers and Renand provide a theory that explains the appeal of this French furniture company. Vickers and Renand explore the success of luxury brands in sectors such as perfume, jewelry, watches, cars, wine, and more. They argue that French luxury goods specifically “have traditionally been seen perhaps as the sine qua non of the rich and famous everywhere” (Vickers and Renand). While furniture is not a luxury market they discuss, Fermob’s price point and marketing certainly make it a luxury brand in the furniture market. This tendency to see French luxury goods as the “sine qua non,” an essential good or necessity, among the rich reveals how French luxury goods are perceived as more prestigious and carry more status. WashU and other colleges may have been attracted to this “expression of French culture” because of the connotations of luxury and royalty that it carries.

Additionally, the Fermob chairs are prestigious because of their presence at other prominent American institutions, and primarily elite universities. Fermob’s press release reveals that the company has built partnerships with a diverse range of institutions including public spaces like Times Square, corporations like Google, and universities like Harvard (Harmon and Ratto). While Fermob’s presence at any such prominent institutions likely enhances the prestige of the company and furniture, Fermob also has a very strong presence at WashU’s peer institutions. Fermob furniture can be found on the campuses of Harvard University, Duke University, Stanford University, and several other higher education institutions in the US. This relationship began when Harvard purchased Fermob’s furniture in 2009, and the order was “such a success that other orders quickly followed” (“Fermob”). This choice of identical furniture across so many college campuses is unexpected because these colleges exist in distinct parts of the country, appeal to different students, and have unique cultures and campus styles. However, in the essay “Spending Up the Ranks? The Relationship Between Striving for Prestige and Administrative Expenditures at U.S. Public Research Universities,” McClure and Titus reveal that it is quite common for colleges to imitate each other when seeking prestige. They claim that “lower-status groups tend to imitate higher-status groups as a way of earning group honor” and that this competition “tends to be most intense among groups near the top of the hierarchy” (McClure and Titus). Institutions like WashU and Harvard certainly belong in the “top of the hierarchy” of college rankings in the US. However, according to university rankings and social reputation, Harvard is comparatively a “higher-status” institution than WashU. When Harvard purchased the Fermob chairs, the furniture gained a prestigious status that WashU and other colleges sought to achieve through imitation.

This purchase reveals a larger tendency of colleges to pursue prestige and gain reputation through symbolic and artificial purchases. In the essay, “Toward the Model of University Image: The Influence of Brand Personality, External Prestige, and Reputation,” Sung and Yang argue that many academic institutions have begun investing in image and brand personality to attract students and strengthen their reputation. Especially in an increasingly competitive landscape among prestigious colleges, university image and marketing can have considerable influence on that institution’s ranking and prestige (Sung and Yang). This often means that colleges invest in symbols that make their campus more attractive. However, Sung and Yang also clarify that prestige-oriented purchases contribute to image and not necessarily to long-term reputation. They state that reputation is “something dependent upon actual experience of the organization” while image is “an opinion that is independent of actual experience” (Sung and Yang). This implies that a college’s use of prestigious symbols, such as the Fermob chairs, does not alter the “actual experience” students or visitors have with the campus, but rather simply benefits the university’s image. While these superficial investments may seem futile if they do not alter reputation, Sung and Yang argue that image can help create an “enrollment funnel” by building “emotional attachment and loyalty” among prospective students. Because the college ranking system is highly dependent on the acceptance rate and the rate of accepted students that commit, this “enrollment funnel” directly benefits colleges’ rankings.

However, this prioritization of image and prestige over student needs reveals how colleges have become commodified and profit oriented. Sung and Yang suggest that, although universities are meant to be “service-oriented institutions,” corporate and university models have many similarities. The parallels between the two sectors are clear specifically in their approaches to marketing and brand image or personality creation. Sung and Yang explain that in both fields institutions pursue a positive image in order to drive sales, enhance loyal customer relationships, build a positive “perception of quality,” and strengthen consumer attachment to the company. By framing students as consumers and admittees as sales, colleges have commodified the individuals they are meant to serve. Furthermore, the focus on building “perception of quality” rather than actually improving quality also displays how colleges are moving further away from their “service-oriented” missions. Rather than attempting to fulfill their responsibilities to the students that they have already enrolled, universities rely on manipulative and superficial techniques, such as making their campus more attractive, to entice prospective students and gain profits.

This commodification of higher education has the dangerous consequence of marginalizing low-income students. As colleges become increasingly concerned with profits and see students as avenues of revenue, they begin catering to and prioritizing students and families with the most means. Purchases like the Fermob chairs would only benefit a college’s image if the audience has the cultural capital to recognize the prestige and status of the investment. In the case of the Fermob chairs, that individual would likely have had to visit the Luxembourg Gardens, elite universities, or prestigious institutions, in order to recognize the chairs. To have this extent of cultural capital, that individual would also likely be of a higher socioeconomic status. By choosing to invest in these symbols that would only carry significance to affluent individuals, WashU and other such colleges are communicating their primary target audience. They aim to attract students of higher economic means because these students would maximize the most profit for the university. Not only does this strategy prioritize affluent students, but it also harms and marginalizes low-income students because it undermines their ability to attend such institutions. Especially at WashU, which is infamous for having one of the lowest rates of socioeconomic diversity and just recently implemented a need-blind policy, low-income students are already at a significant disadvantage. Additionally, making such a large investment in superficial symbols to attract wealthier students is both insulting and a deterrent to those that lack the financial ability to attend WashU. In the Reddit threads where community members discussed WashU’s purchase of the Fermob chairs, one student called the purchase “outrageous” and argued that just “one of those chairs could pay my rent” (u/okay_but_what). This outrage reveals students' frustration towards WashU’s spending on symbolic purchases rather than greater support and outreach to low-income students.

Furthermore, the prioritization of profits and the commodification of higher education often means that colleges fail to meet the needs of their community members. Although Fermob likely offered a discounted price to college partners, WashU purchased around 250 Luxembourg chairs and 350 bistro chairs along with 175 bistro tables from Fermob (McCarthy). Even with a significant discount, the price range for this purchase is enormous. While such decorative purchases may help boost college rankings, they also divert funding from initiatives that would serve their current students and staff. Most elite institutions that make such purchases, including WashU, fail to address their community members’ most basic needs, such as mental health resources, adequate scholarships for low-income students, sufficient pay for staff members, and protection of student-athletes. In the Reddit thread discussing WashU’s Fermob chairs, one commenter states, “‘university wastes money on decorations/campus improvements while neglecting students’ seems like a classic move” (u/okay_but_what). This belief among students that their college will neglect their needs in order to prioritize spending money on “decorations,” reveals that colleges are failing to meet their “service-oriented” mission. Moreover, this student concern is not specific to WashU. Harvard University’s newspaper, The Crimson, featured an article reporting on the same Fermob chairs on their campus and revealed that these chairs have been “the star of several articles, Quora queries, and even TikTok’s” where students question why Harvard is spending tuition money on such expensive chairs (Mui).

The purchase of prestigious symbols is especially problematic and irresponsible during the height of a pandemic. Although it is impossible to have a perfect response to an unprecedented and unforeseen pandemic, almost every community member of WashU and most elite colleges could list a multitude of ways that the university could have better supported their students and staff through this crisis. Despite the lack of clarity on whether this purchase came out of the COVID-19 response budget, WashU’s justification of this purchase as a social distancing strategy is problematic regardless. The massive funds that were applied to this purchase could have been spent on ensuring adequate testing, improving isolation and quarantine housing, compensating RAs and other student employees for their efforts, or offering better support to faculty and staff instead. WashU’s attempt to paint this purchase as one motivated by safety and preparedness only further reveals the failure of their pandemic response. If placing outdoor chairs is one of the most prominent responses to the pandemic, WashU ultimately failed to launch the necessary substantial COVID relief or safety measures.

Although the Fermob Luxembourg chairs on WashU’s campus may simply seem like lawn chairs, they reveal a dangerous pattern in the spending habits of academic institutions. As universities compete to improve their ranking, there is a greater incentive to spend budget on decorative features that strengthen the campus image. However, this choice prioritizes a college’s profits and rankings over the well-being of its students and staff and reveals how institutions of higher education function as businesses. This pattern is unfortunately not exclusive to universities nor a singular choice by administrators, but rather a symptom of America’s highly capitalistic culture. Even service institutions that are meant to provide access to basic rights such as food, water, education, or healthcare, are driven by making profits and maximizing revenue rather than serving the public. In doing so, they fail to recognize the needs of their community members and neglect their responsibilities to serve them. Furthermore, these institutions primarily benefit the wealthiest populations because they guarantee the greatest profit despite not having the greatest need. As long as American society, with its growing capitalistic tendencies, continues to view human needs as markets for profit and human beings as customers, we will continue to prioritize privileged groups and disregard underserved and marginalized populations.

Works Cited

"Collection Luxembourg." Fermob, fermob.com/en/Products/Flagship-collections/luxembourg. Accessed 19 Apr. 2022.

"Fermob Goes to College with 'Universities by Fermob' Program." Casual Living, BridgeTower Media, 17 Nov. 2014, casualliving.com/deep-seating/fermob-goes-college-universities-fermob-program/. Accessed 18 Apr. 2022.

Harmon, Sarah, and Alli Ratto. "Fermob Corporate Press Kit." 2019.

"Luxembourg Gardens." Project for Public Spaces, 7 Jan. 2022, pps.org/places/luxembourg-gardens.

McCarthy, Leslie Gibson. "Campus Space in a COVID World." The Source, 18 Sept. 2020, source.wustl.edu/2020/09/campus-space-in-a-covid-19-world/. Accessed 18 Apr. 2022.

McClure, Kevin R., and Marvin A. Titus. “Spending Up the Ranks? The Relationship Between Striving for Prestige and Administrative Expenditures at U.S. Public Research Universities.” Journal of Higher Education, vol. 89, no. 6, Nov. 2018, pp. 961–87.

Mui, Christine. "Flyby Investigates: Those Famous Harvard Yard Chairs." The Harvard Crimson, 13 May 2020, thecrimson.com/flyby/article/2020/5/13/flyby-investigates-yard-chairs/. Accessed 1 May 2022.

Sung, Minjung, and Sung-Un Yang. “Toward the Model of University Image: The Influence of Brand Personality, External Prestige, and Reputation.” Journal of Public Relations Research, vol. 20, no. 4, Oct. 2008, pp. 357–76.

U/okay_but_what. "The Chairs." Reddit, 19 Oct. 2021, reddit.com/r/washu/comments/qbmuxd/the_chairs/. Accessed 2 May 2022.

Vickers, Jonathan S., and Franck Renand. “The Marketing of Luxury Goods: An Exploratory Study--Three Conceptual Dimensions.” Marketing Review, vol. 3, no. 4, Winter 2003, pp. 459–78.

Priya Anand is from Ambler, Pennsylvania, and studies political science in the College of Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

Washington University in St. Louis

@REMAKE 2023